Diagonal interventions transform both of Arthur Jafa’s concurrent exhibitions in New York. Picture Unit (Structures) II (2024) is a plexiglas passageway that cleaves 52 Walker, David Zwirner’s Tribeca outpost. Images from Jafa’s archive wrap the interior walls of the unit and the exterior is clad with mirrored acrylic that reflects an array of surrounding sculptures, paintings, and a new hour-long video. At Gladstone Gallery on 21st Street, a nearly 52-foot long wooden wedge juts across the darkened space where a 73-minute video, ***** (2024, pronounced “redacted”), is projected above a polished concrete floor. As an unconventional bench and spatial bisector, the wedge materializes many of Jafa’s cinematic tendencies. As a tool, a wedge can split apart, raise up, and achieve balance. So does Jafa's practice.

With early camera credits including Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust (1991) and Spike Lee’s Crooklyn (1994), Jafa's career further bloomed when he began making short-form moving image artworks that were fluent critical inquiries of racism and visual media and also, almost, music videos. These include APEX (2013), propulsively edited to Robert Hood’s “Minus,” and the crossover hit Love Is The Message, The Message is Death (2016), set to Kanye West's “Ultralight Beam.” Around this time, Jafa also directed a feature-length documentary, Dreams Are Colder Than Death (2014), which edits interview footage into Jafa’s vernacular: images of sublime cosmos and microbiology collaged alongside earthbound views of ecstasy and grief, from preacher to slave to alien to bacterium to hadron collider.

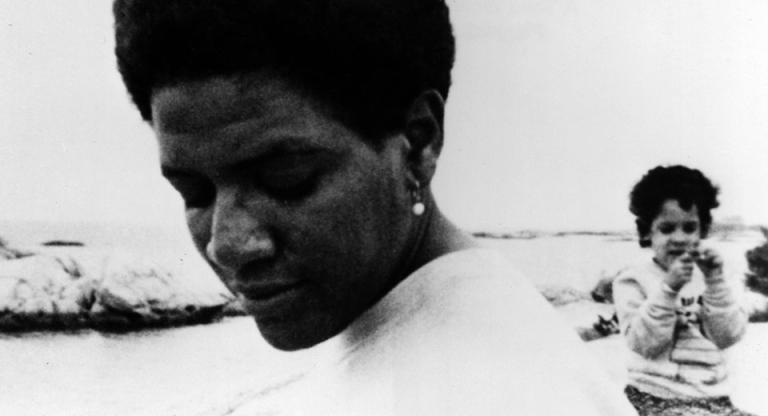

With the new work, Jafa continues his focus on sequences of passion and violent destruction, using the wedge and the tools of cinema to un-redact—and thereby reveal—the racist thirst for blood coursing through veins onscreen and off. In “The Deflected Corrected,” an essay published to accompany the new exhibition at Gladstone, Amy Taubin introduces ***** as “a digital motion picture installation, in which the climactic, approximately seven-minute massacre scene from Taxi Driver, with alterations and additions, plays on a loop.” When he first saw Taxi Driver as a young man in Mississippi, Jafa was attracted to the high-contrast expressionism of the visual images and soaring score. He was also disturbed by what he registered as racialized and racist elements in the film.

As Taubin writes, the Times Square of the 1970s, which was the cruising ground for the title character, “was populated almost entirely by black people. Unlike the black characters in early 1970s Blaxploitation movies, in Taxi Driver, they are treated merely as background color.” Paul Schrader’s script initially called for Robert DeNiro’s Travis Bickle to unload his weapons into people of color in the brothel, but when Martin Scorsese and Schrader worked through the script to make the film, they made Iris’s pimp and the other men white because otherwise “there would be riots in the theaters.” Taubin argues compellingly that the “gamble made with Taxi Driver was that if the only black person Travis kills is a junkie attempting to hold-up a Puerto Rican bodega owner… we won’t notice that Travis’s racism is as all-consuming as white supremacist Dylann Roof’s.”

Jafa’s brilliance in recasting the pimp and six others is that he allows us to more clearly see what was there all along, while also speculating on and embellishing the interiorities of characters not given much of any attention from the original makers of the film. We still hear the entrancing harp and booming orchestra of Bernard Hermann’s score, but other sounds are muted and then foleyed in, resulting in a ghostly ASMR. Each varying repetition of ***** offers an extended contemplation of the psychosis and carnage on view.

As with all of Jafa’s work, the film is like a DJ set. Some rhythms are stretched and slowed down, other elements are distorted, and the embodied audience has the chance to move and follow along, ready for a momentary break from the cycle of terror. In one such a moment near the end of *****, Travis puts the gun to his head and pulls the trigger, but this time there’s a bullet in the chamber. Down he goes. In this alternate reality, the pimp at the front is still alive, singing along to Stevie Wonder and spitting a beautiful cigarette soliloquy. But the next time the loop comes around, he will not be so lucky. His white suit will again be drenched in blood.

While the off-kilter Picture Unit is technically the centerpiece of the 52 Walker show, Jafa’s strongest work here is LOML (52 Walker Version), a moving image elegy dedicated to his dear friend and collaborator Greg Tate (1957-2021). Unlike *****, which takes a singular filmic source material and endlessly reworks it, LOML melds screen recordings of Instagram Reels with bystander footage of police shootings, climatological documentation, and extended footage of performing musicians.

After a nearly 20-minute ambient “break” in which there is no image and not much sound beyond undulating rumbles, Jafa cuts back to a procession of imagery from SloPEX (2022). This sequence includes black-and-white photographs of Jimi Hendrix, microbes, Beyoncé, the Sun, and the Warner Music Group logo upside-down, all set to a throttled throb. The choice to follow this segment with almost five full minutes of a slowed-down recording of Donna Summer singing “I Feel Love” is a microcosm of Jafa’s magistery, extending Summer’s voice and movement, deploying the potency of the music itself and its relational function within a web of material.

As with Jafa’s The White Album, which paid special attention to twisting and tangling hair, LOML features multiple self-recorded videos of women having their hair done in home-studios, collapsing any distinction between sites of living, working, and performing for the camera. A cut to heavily post-produced footage of African-American sorority sisters in the South throwing their hair around and “getting loose” reiterates Jafa’s preoccupation with the constricting, malleable, and expressive qualities of hair.

Donna Summer’s arms rise and lock into formation, cradling her body and then cradling all that is beyond it. LOML begins and ends with grainy black-and-white footage that could also be views of writhing, shifting figures. Is what we’re seeing light passing between bodies? These 11 minutes of intimate footage, which comprised the original iteration of LOML before it became the expanded (52 Walker Version), is the heart of the matter. It’s as if, for the Tribeca exhibition, Jafa wedged a musical shard into the center of it.

BLACK POWER TOOL AND DIE TRYNIG is on view through June 1 at 52 Walker and ***** is on view through May 4 at Gladstone Gallery.

Image: Arthur Jafa, *****, 2024, installation view, courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery