Pleroma, in Greek, means “full perfection.” In Gnosticism, the pleroma is the spiritual universe of divine powers and emanations. Transmissions from the Pleroma is an exhibition of works by the late Texan artist, composer and occultist Jerry Hunt (1943–1993) at Blank Forms. Having cut his teeth performing piano accompaniment in strip clubs owned by Jack Ruby, Hunt emerged in the 1960s new music scene with studiously composed and often inscrutable scores. Stabile w/ Cylindrical Surface (1964) was written “for single object or not / employing movable or immovable parts or areas.” Hunt became a pioneer of live electronics, gesture-reactive generative sound systems, and live-streamed audiovisual signals. In 1983, Hunt performed in the first virtual concert in the US facilitated by satellite, processing live cello music that was beamed to him in Texas and then fed back to where the cellist was playing in Washington, DC. Hacking, reprogramming, storing, and transmitting became important concepts in Hunt’s repertoire, and even before the mass availability of personal computers Hunt remarked, “There’s a psychological aspect of music I’m interested in, which is memory.”

Facing a terminal lung cancer diagnosis and the reality that much of his live performance work had not been recorded and might not be remembered, Hunt turned to video in the last years of his life. He saw video as a medium that could syncretize his performances into enduring, magnetic emissaries of the work after death. Four of these late works, posthumously released as “Four Video Translations,” are featured in the exhibition at Blank Forms, each worthy of close looking and listening. Together, they generate an opportunity for Hunt’s radiant presence, humor, and intensity to light up a room again.

Talk (slice): duplex (1993) is a hilarious and deadpan work about conversational expression, and speaks to the sometimes didactic modes of Hunt’s lectures and performances. In the video, Hunt and his interlocutor Rod Stasick face off but seem to talk past one another in an unending flow of non-sequiturs that skate toward profundity before veering into interruption and inanity. We are always just on the edge of deliverance, one word away from the answer. As the video ends, another begins from another direction, and the soundscape in the exhibition produces an atmosphere of rich kinetic experimentation. This new clamor animates the viewer, who moves among the monitors and the many wands and staffs leaned against the gallery wall.

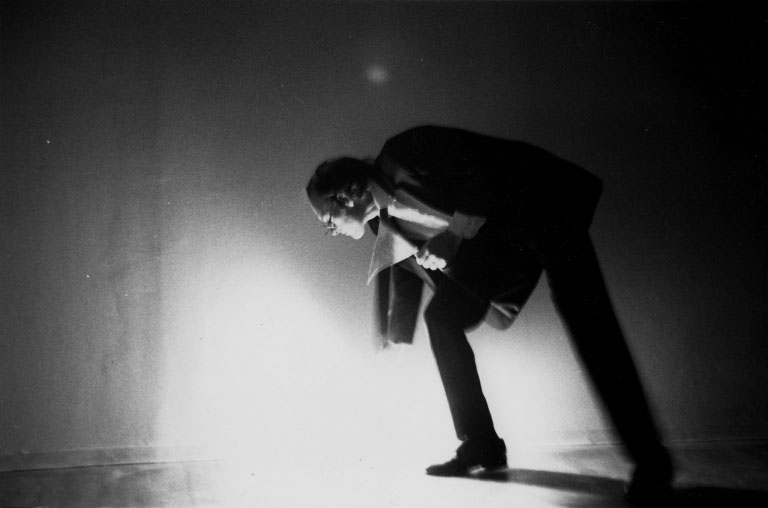

Rather than a musician, video artist, or performance artist, Hunt came to think of himself as a manipulator of performance conventions. Conductor. Mime. Playful guide. The performances articulated a language of gestures inscribed with technological or homespun implements, best exemplified in the video Birome [zone]: plane (fixture) (1993). A fixed shot looks down on Hunt as he sits on a stool and holds intense eye contact with the camera, unselfconsciously playing a series of musical objects and hitting himself rhythmically with reeds like a spasmodic wizard. His mouth opens and eyes pop as mysterious objects appear to fly close to his head and torso.

When critics began referring to his experimental audiovisual performances as shamanistic, Hunt accepted the moniker, acknowledging that his work “disorients the audience with respect to the usual conventions of concert performance or museum installation.” Much of Hunt’s work emerged from a close study of Kabbalah, Tarot, and other “soft divination mechanisms,” esoteric practices key to John Dee and Edward Kelly’s 16th-century Enochian tablets. The occult grounding paired with Hunt’s innovation with circuitry systems led him to produce music alongside a visual language to translate the sound, a process he described as the “signing of sounds.”

At Blank Forms, audiences can sway, sit in rapt awe, pore over the ephemera in display cases, or crouch among the wands Hunt produced as a collaboration with his friend and assemblage artist David McManaway. Some of these were contributed to the exhibition by the artist Shelley Hirsch, who shared bills with Hunt and went on to perform homages to and virtual duets with him beginning in the mid-1990s. Hirsch’s championing of Hunt encouraged Blank Forms artistic and executive director Lawrence Kumpf to mount the show, which he co-curated with Tyler Maxin.

Together with managing editor Ciarán Finlayson, Kumpf and Maxin produced a 368-page exhibition catalog, which includes Hunt’s wide-ranging 1986 interview for the Canadian avant-garde magazine Musicworks. In it, Hunt answers questions about his mimetic transactional exercises by asking more questions about his work and the role of his audience. “Why am I displaying for you? Why are you allowing yourself to watch me? What are you getting out of me? What can I extract from you? How can we do this with the convention of music being made to go on?”

In the absence of Hunt’s corporeal body, the works gathered in Transmissions from the Pleroma demonstrate Hunt’s preoccupation with ideas still relevant for experimental musicians and performing artists. The heavenly machine still grinds. Upon walking into Blank Forms, you may hear what sounds like a 3D printer and a telecopier both dialing up for instructions. You will know that you are in the right place.

Jerry Hunt: Transmissions from the Pleroma will be on view through June 11 at Blank Forms. Tomorrow night, June 3, Raven Chacon, Yasi Perera, and C. Spencer Yeh will perform Hunt’s composition GROUND : Field (transform de Chelly) (1981).