The following is the first of three dispatches between Screen Slate writers Jon Dieringer, Maxwell Paparella, Jeva Lange, Chloe Lizotte, and K.F. Watanabe about the 59th New York Film Festival.

Jon Dieringer

The annual New York Film Festival offers an opportunity to take the temperature of film culture in our resilient city, a task that feels especially necessary in our changed world. Amid the gradual, if tentative rollback on Covid restrictions, NYFF returns to something like normal after last year’s hybrid drive-in/online edition, which was deftly assembled by a newly restructured team including Eugene Hernandez as director, and a main slate selection committee of Hernandez, Dennis Lim, Florence Almozini, K. Austin Collins, and Rachel Rosen. In light of the dramatic shifts behind the scenes—this is the team’s first “normal” festival—it’s impressive to consider how familiar this year’s rituals feel, like muscle memory for longtime festivalgoers. But this familiarity is somewhat betrayed by conspicuously stronger programming; it’s difficult to remember the last time that the opening, centerpiece, and closing night films all felt so essential—in this case Joel Coen’s The Tragedy of Macbeth, Jane Campion’s The Power of the Dog, and Pedro Almodóvar’s Parallel Mothers, respectively.

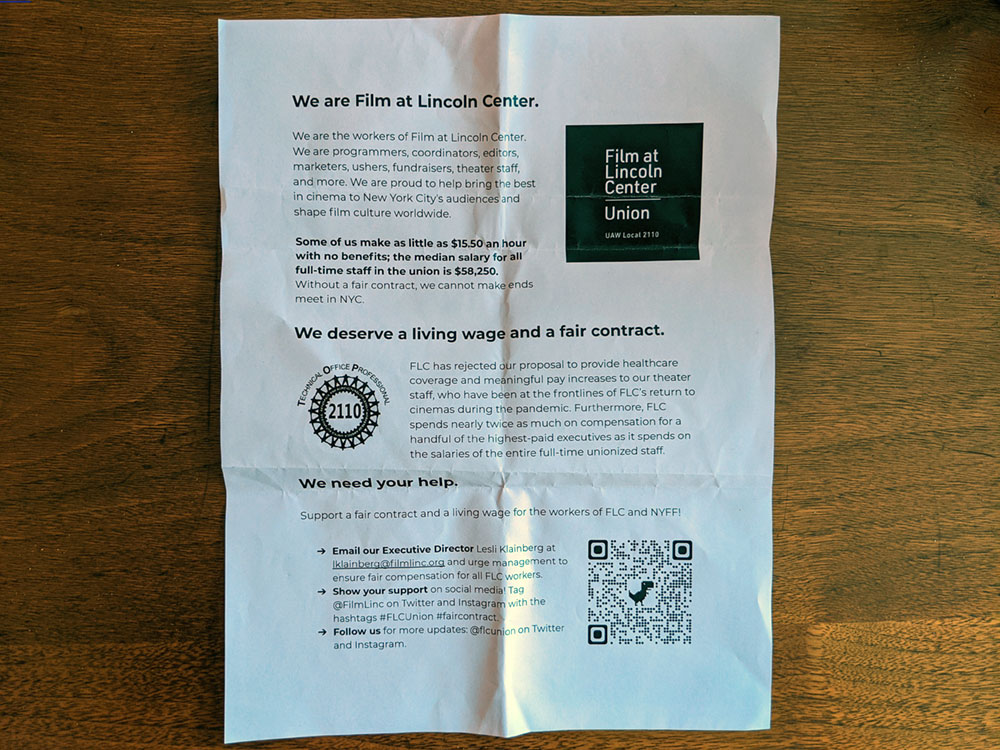

If this year’s NYFF feels similar-but-improved, the broader landscape of film culture is still shifting in directions that are to-be-determined. For-profit venues like Alamo Drafthouse and Metrograph have seen major changes, with key layoffs at Alamo’s lucrative Brooklyn location, and the exit of Metrograph staffers including its founding artistic director, programmer, and publicist. In the nonprofit world, culture workers are asking questions about fair compensation in a sector in which dedication to the mission is often used to justify lower wages and fewer benefits—considerations that feel more urgent in a time of increasing income inequality, when billionaires’ wealth has swelled during a global crisis, and as many as twelve million Americans lost employer-provided health insurance during a pandemic-driven recession. In this climate, a pre-Covid wave of unionization at institutions such as The New Museum, MoMA, and BAM has continued as workers at Film at Lincoln Center and Anthology Film Archives have also voted to form unions.

Outside Alice Tully Hall on Friday, as audiences lined up for the opening night screening of Joel Coen’s The Tragedy of Macbeth, FLC employees leafletted in support of their contract negotiations, just as they also had outside the 46th Chaplin Award Gala honoring Spike Lee on September 9. According to their flyers, in addition to a huge disparity in pay between executives and staff, FLC has rejected the union’s proposal to provide healthcare coverage for theater staff, “who have been at the frontlines of FLC’s return to cinemas during the pandemic.” The term “frontline” was echoed in the first of several introductions to the 9pm screening of Macbeth. The first speaker, who did not introduce himself but seemed to be a key board member, thanked the “frontline” theater staff, and said something to the effect of, ‘and as of this week, they are eligible for booster shots, which we are very happy about,’ an apparent reference to new city guidelines. But who gives a fuck about booster shots? Theater employees deserve healthcare coverage.

In another of several introductions, an impeccably styled Lim dedicated the festival to the late Melvin van Peebles, whose Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song shows in a new restoration, and to NYFF co-founder Amos Vogel, whose centennial is celebrated in a series of programs at FLC and other New York cinemas, and whose essential Film as a Subversive Art has just been reprinted. With his membership screening club Cinema 16, run with his wife Marcia, Vogel established the paradigm for New York City film culture. His boundlessly curious, playfully seditious, and occasionally didactic programming voice continues to influence those who have followed in his footsteps, among them Jonas Mekas, who arrived in New York shortly after Cinema 16 was established. The two had a complex and often fraught relationship; Mekas seems to have adopted something of a kill-your-idols approach to Vogel, whereas Vogel, who has always scanned as the more humble of the two, told Scott MacDonald in 1983, “I was never a very sophisticated person about power relationships.” This attitude extended to his exit from Lincoln Center only five years after the Festival’s founding: “These were signs of a growing commercialization of cultural life I was opposed to. My cinematic talents did not encompass coping with corporation heads. I resigned my post in 1968; a step I have always felt sad about and never regretted.”

If Lim’s attempt to dedicate the festival to “subversion” in an era battered by an intervening fifty-four years of capitalist putrification of cultural life in America is a tad eyebrow-raising, it does feel, relatively speaking, accurate. After all, Radu Jude’s Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn, a Romanian political history lesson with hardcore unsimulated fucking, echoes Film as a Subversive Art’s cover film W.R.: Mysteries of the Organism (1971). Sunday evening, the festival experienced an old-school religious picketing by a Catholic group called The American Society for the Defense of Tradition, Family and Property, who demonstrated outside “the blasphemous lesbian movie Benedetta, that insults the sanctity of Catholic nuns,” as its banner read. There is some speculation as to whether the protest was orchestrated hype—NYFF’s Twitter was quick to capitalize on it—but theater or not, we love to see it.

Whether Benedetta is truly blasphemous is maybe up for debate; yes, it is a movie from the director of Basic Instinct (1992) and Showgirls (1995) that graphically portrays sisters in the act of penetrating each other with a statue of the Virgin Mary. But. The director of Basic Instinct and Showgirls is also published on the subject of historical Christ and is the only non-theologian admitted to the prestigious Jesus Seminar. Benedetta comes across as an attempt to portray palace intrigue and politics within and around a 17th-century Tuscan convent. Benedetta (Virginie Efira) is a nun who claims to experience the stigmata, which upsets the dynamics of the abbey, promoting her into the seat of its longtime abbess (Charlotte Rampling). All aspects of the abbey’s existing power structure are in some way or another hypocritical or corrupt, and the film leaves it mostly open to interpretation whether Benedetta’s wounds are divine and/or whether she believes them to be. (In this sense, as Verhoeven has acknowledged, the film is ironically not dissimilar from Total Recall [1990].) There is also a question of righteousness, religious and otherwise, which deepens with the introduction of Lambert Wilson as the nuncio, a vulgar official who represents the patriarchal order of the church. (That this movie will be released the same month as Wilson reprises his role as The Merovingian in the fourth Matrix film feels like an act of divine providence.) As a conflict between a cool, conniving lesbian and a corrupt church official, Bendetta is not so different than Basic Instinct or its noir forerunners in pitting a “bad” woman against a worse social and political order dominated by men. Manna from heaven for fans of Verhoeven, the problematic feminist.

And as that epithet is concerned, a new challenger enters the ring: Julia Ducournau, whose Palme d’Or–winning Titane seems to be generating new cycles of backlash and counter-backlash on a daily basis. I caught the same press screening Chloe mentions below, and while there were no walkouts, projectile vomitings, or fainting episodes, I did clock an elderly member of the press snoring about an hour in. The first half hour or so of Titane is epic: a woman twerks on the hood of a car, stabs a guy, fucks a car, fucks a girl, stabs a girl, kills her roommates, discovers she’s pregnant with the car’s baby, and performs lo-fi reconstructive surgery on her own face by bashing it against a sink so she can impersonate a lonely firefighter’s long-lost son. Then it settles into a pretty chill register. Personally, I thought it was great. I can’t say I’m on the same wavelength as commentators who see Ducournau as a cynical, provocative shock jock. Her setpieces are painful; like Argento or Fulci, she knows the body’s most sensitive pressure points and how to inflict agony on them. But I think there’s something very earnest about the film and its character’s yearning to destroy and remake her body.

I’ve way overstayed my welcome so will turn things over to my colleagues, but in coming dispatches I look forward to digging more into revivals such as Chameleon Street (1989), Sambizanga (1972), and Kummatty (1979), as well as more of the Vogel program.

Maxwell Paparella

Since I have lived in New York, I have marked the beginning of autumn with panicked morning sprints from Columbus Circle to press screenings at the New York Film Festival. For myself and many others, last year's mostly virtual iteration left a hole in our fair city’s fairest season. Even the drive-in screening I had hoped to see (of Ephraim Asili's The Inheritance) was canceled due to high winds. The workers of Film at Lincoln Center deserve the highest praise for getting us safely back into the soft seats this year. (One might even say they deserve a fair contract and a living wage!)

The P&I screenings kicked off with Benedetta, which marks new heights for Paul Verhoeven's potty humor and his willful fantasies. It is one of two films so far that admit the commode as a site of flirtation (the other being The Worst Person in the World). The film also features the first of several show trials we've seen so far in the festival, with another notable one at the end of Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn.

Three films this week were set in the Middle East: one narrative and two nonfiction, two from Israel and one from Denmark. Both Israeli films address that country's racist nation-building project, though they do so without giving voice to Palestinians themselves. Avi Mograbi's The First 54 Years: An Abbreviated Manual for Military Occupation is primarily composed of interviews with former IDF soldiers who are now involved with the dissident organization Breaking the Silence. Their memories of tours of duty are illustrated with archival footage, and Mograbi situates the various tactics of intimidation and abuse as part of an ongoing, totalizing occupation. He speaks in the second person, satirically instructing the viewer on how to manage their own open-air prison. Intriguingly, the interviewees frequently do the same ("These are things you do,” one says, “It’s part of the job.”), often accompanied by the passive voice ("A decision was made," or, horrifyingly, "the club banged into her."). Many of them can't help but laugh or smile as they recount these events—tying a man to a tree for the night or shooting at children playing in a landfill—whether from nerves, a sublimation of the aggressor's trauma, or residual bravado. Startling, then, to hear someone refer to the film’s “Palestinian perspective” on the way out.

With Ahed’s Knee, director Nadav Lapid seems to engage in some autobiographical fabulation. A middle-aged Israeli filmmaker is invited to show his film in a remote village in the Arava desert. A piece of paperwork which prompts him to specify the theme and approach of his artistic inquiry from a list of approved topics. He stridently objects to the formality and begins to plot against the young woman from the Ministry of Culture who has invited him. I was not with this film all the way, but I admire how it makes loathsome the director's blinkered, chauvinistic self-righteousness without equivocating on the fundamental integrity of his convictions.

Meanwhile, Flee tells the story of Amin, an Afghan man who was made a refugee as a child. In rotoscoped animation, it illustrates his flight from Kabul to Moscow, and eventually to Copenhagen, as well as his adult struggles with intimacy and commitment. Until now, we learn, Amin has only ever given a false account of the circumstances of his arrival in Denmark, retelling the story he was given by the trafficker who secured his passage. This detail is sure to spark controversy in Scandinavia, where debates rage as to the admission of refugees, with those on the right often leveling accusations of deception at asylum-seekers. If a film might be an empathy machine, per Ebert, then one hopes this one will be widely seen.

I’m less convinced by another documentary I saw this week. Futura is a continuation of the long Italian tradition of candid interview films with young people—from Luigi Comencini to Mario Soldati to Silvano Agosti and others—some of which are even excerpted here. The filmmakers travel across Italy, the bel paese, speaking with teenagers from many walks of life. Unfortunately, the line of questioning veers quite superficial and career-oriented, and the results of their inquiry are broad but not deep. Still, the subjects are largely well-spoken, evidently concerned with beating back the individualism they see in the world with a form of communalism. Working with teenagers, one is sure to encounter their brutal eloquence: "Thoughts are often very different,” one considers, “from the things you say out loud.”

I have avoided Gaspar Noé's films until now; from everything I’ve heard, they are not my bag. So I was surprised to find myself so affected by Vortex, which I understand is a departure from his usual act. Nearly the entire film occurs in split-screen, with the two cameras typically following either member of an elderly couple (Dario Argento and Françoise Lebrun), but also their son (Alex Lutz). The mother and father squeeze their stiff, lurching bodies around the cramped, cluttered apartment in which they have spent their lives. He pecks out words on his typewriter toward a book on "film and dreams" while she struggles with ever-worsening dementia and uses her old medical license to write her own prescriptions. I found the film a really perceptive reckoning with the age at which death becomes the next thing, the vacancies and overwhelming fullness of lives that have been mostly used up.

Like Jeva, I enjoyed Bergman Island, in which Mia Hansen-Løve allows her avatar (Vicky Krieps) only the fantasy of a frustrated encounter. Just as her night's cry does not resolve with sleep, I'm finding myself picking through the implications of this film days later. And, like Kazu, I was completely taken with Il Buco, in which two worlds uncertainly combine. The words that pass between speleologists are like those of a herdsman to his flock: untranslatable, functional, deeply resonant. I wrote about Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn, Titane, and The Tsugua Diaries under separate cover.

Until next week—see you at the movies, gang!

K. F. Watanabe

It’s been two years since I saw 75-year-old writer Philip Lopate in a near full sprint on West 65th Street, running to make it to a New York Film Festival press screening at the Walter Reade Theater on time—an endearing and familiar sight. I thought of him as I hustled my way down the same street to the first NYFF press screening, Paul Verhoeven’s erotic lesbian nun drama Benedetta (full disclosure: I arrived ten minutes late). Having read his book on the historical Jesus, I was sure Verhoeven would find an appropriately provocative and outrageous way to handle a film about Christian devotion, power, sexuality, and martyrdom. But the film exceeded my expectations, proving that the 83-year-old director has not lost a drop of his talent for constructing unforgettable cinematic moments. (I don’t want to spoil it, but it may be hard to look at a statue of the Virgin Mary in the same way again). The appearance of Catholic protestors outside of Alice Tully Hall for the film’s first public screening yesterday should also provide as much of an endorsement as you need. Let’s hope he’ll get to make his dream project Jesus movie.

Also high on the list of anticipated screenings was Il Buco, the first feature film by Michelangelo Frammartino, the director of Le Quattro Volte (NYFF 2010). More than one audience member in the screening I attended succumbed to the film’s slow, deliberate, and meditative pace with closed eyes and nodding heads. I understood the reaction, but I found myself enraptured by the film’s incredible images, finding nearly every shot remarkable in its composition and use of light and darkness. I know I would not have had that experience watching the film through a Vimeo link on my laptop. Let’s hope this finds a US distributor, though on the surface it is a bit of a hard sell: a dialogue-free, documentary-like recreation of a 1961 expedition down the world’s then-third-largest cave, located in the Calabrian countryside of southern Italy. [Full review here.]

I was not quite as enraptured with Futura, though, another Italian film in this year’s Main Slate, co-directed by Pietro Marcello, Francesco Munzi, and Alice Rohrwacher. I agree with Maxwell here, finding the film a little thin and at worst superficial in its stitching together a series of spontaneous interviews about the future with teenagers throughout Italy before and through the current pandemic over the last year and change. (Without the pedigree of the directors involved, I am not so sure this film would have made the Main Slate.) Still, some interesting themes emerge—a sense of isolation from the world, frustration with the adults in charge, desire for opportunity, and a general lack of interest in political action—though insight into the future of Italy remains vague.

A similar lack of clarity is found in the characters of Ted Fendt’s Outside Noise, a low-budget independent film about a young insomniac woman from Vienna who travels to Berlin and back, meeting with old and new friends as she contemplates her next steps in life. While I missed the dry humor scattered throughout Fendt’s earlier films set in the suburbs outside of Philadelphia, I found the film pleasant in its laconic pace—a languorous “hangout film” shot on 16mm that emphasizes the bond between young women finding their way through life outside of college. It is part of this year’s Currents lineup, which is something of a B-side to the Main Slate, providing the festival programmers an opportunity to show some more daring and unconventional films. I hope to dig into more of these as the fest goes on.

Lastly, I was glad to have seen Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s Drive My Car, one of two films by the Japanese director included in the Main Slate lineup—a rare feat shared this year with Korean auteur Hong Sang-soo, who again has two films included. Like Hong, Hamaguchi has become something of an NYC cinephile favorite since the premiere of 2015’s Happy Hour in Locarno and its subsequent screening at New Directors/New Films, after which point his career took skyward. Adapted from a Haruki Murakami story (that I haven’t read), the film centers on a successful stage actor and playwright (Hidetoshi Nishijima) struggling to overcome the sudden death of his wife while going into production on a multilingual staging of Uncle Vanya. Or at least that’s what it is at first, as it slowly shifts its focus over the course of its three-hour runtime to the playwright’s stoic, contractually-necessitated personal driver (Toko Miura), who is dealing with her own familial trauma. Aside from a somewhat unconvincing emotional climax and an uneven performance by Nishijima, the film is a compelling and well-paced drama that evokes the contemplative, transfixing experience of a long, scenic drive. (It also makes you want to seek out a red 1998 Saab 900.) I look forward to catching Wheels of Fortune and Fantasy, Hamaguchi’s other film in the festival this year, and seeing how it compares.

Until then, happy viewing!

Jeva Lange

I spent a good chunk of my Sunday at Lincoln Center—as did, it turns out, the Catholic League. As you mentioned, Kazu, they were protesting the new Verhoeven, Benedetta, a film I have not yet had the opportunity to see. Though from the description of "Verhoeven + lesbian nuns," I have a pretty good idea what the protesters were upset about!

I admit that before the festival, I was a bit of a Benedetta skeptic for that exact reason: the concept, at least on paper, struck me as being almost lazily provocative. But I've heard great things so far ("new heights for Paul Verhoeven's potty humor and his willful fantasies"—okay, count me in!) and I definitely agree with what New York Film Festival Director of Programming Dennis Lim said in his introduction to the film at Alice Tully on Sunday, that "Verhoeven doesn’t provoke without a purpose." Moreover, I don't take for granted being publicly scandalized anymore.

In fact, much of what I've seen at the festival has been provocative in some way or another. My favorite film so far has been Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn, a brilliant Romanian satire. It starts with a pornographic sequence (which I've seen or heard described as both "three minutes long" and "ten minutes long," depending, I suppose, on how squeamish you are watching porn beside strangers) and continues to needle the prudish viewer throughout. Afterwards, I couldn't stop remarking on how proud I was of the NYFF—which I usually count on for fairly safe, wealthy-patron-friendly fare—for the daring selection. I know someone is going to complain about it to them. But I also know it's one of the best of the slate this year.

Titane, likewise, is a film that's engineered to provoke conversation. And while it felt a little transparent to me in that regard, I have to say, watching it last night in a sold-out Alice Tully crowd was a moviegoing experience unlike anything I've experienced since 2019, and maybe even before that. Getting to hear a thousand people cheering as the title card appeared, or listening to the audible gasps of horror, or squirming nearly into my neighbor's lap (and him into mine) as we tried to half-look away … man, that's the moment it hit me that the movies are back. And it sure does feel great.

More soon.

[Jeva also wrote about Haruhara-san’s Recorder and Bergman Island.]

Chloe Lizotte

Hello everyone! Really happy to return to the virtual roundtable this year.

While walking to the Walter Reade for the first day of press screenings—for anyone who might be reading outside of New York, you need to walk up a lengthy set of stairs to reach the theater, which invites some final ambient contemplation—I realized I hadn't returned since before the pandemic. As I filed into the familiar line and greeted the theater staff, I was not overwhelmed by memories of moviegoing, but of working for the festival's hospitality team a few years ago, and the immense collective effort it takes to mount a festival of this size, pandemic times or not. So I'd also like to start by voicing strong solidarity with the Film at Lincoln Center Union.

Reading everyone's dispatches has me feeling a bit like I'm missing out on some of the highlights! I'm saving the first-watch thrill of some movies until I can see them with specific groups of friends, like Benedetta. I don't know if it's just me, but aside from writing commissions and some uber-favorites like Joanna Hogg, I'm trying to avoid binge-viewing the festival titles—not because I don't enjoy them, quite the contrary, but because this past year has made me feel grateful to see any new movies at all. Especially when there's a US distribution plan in place, I'm happy to deliberately savor space between cinematic discoveries and not succumb to the rush to react to them all at once. (My slow-processing brain is also tacitly part of my reasoning.)

At the risk of sounding too repetitive, Jeva, my favorite film so far has also been Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn. I am always drawn to filmmakers that aren't scared of tackling the present, so I was moved that Radu Jude found an inspired way to make that prospect the central idea of his film: the ways in which we blind ourselves to contemporary hypocrisy and rationalize historical atrocities. It's also, of course, very, very funny—I think Jude must be the first filmmaker to convey character through tacky face-mask fashion choices.

I've been enjoying burrowing into the Currents lineup. I fell hard for Maureen Fazendeiro and Miguel Gomes's The Tsugua Diaries, another Covid-era film that we quickly realize is unfolding in reverse (but that's only the first of many light revelations). It's a playful, organic meditation on filmmaking and collectivity, bookended by lushly gel-lit party scenes set to Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons’ supreme “The Night.”

I'd also recommend Kiro Russo's expressionistic sophomore feature El Gran Movimiento. It follows the central character from Russo’s first film, Dark Skull (2016), a Bolivian miner suddenly plagued by a mysterious illness. Russo has a hypnotic command of light and darkness, which creates an unsettling atmosphere for his depiction of a precarious life on La Paz's economic fringes. The film also features one of the most surprising, and dare I say poignant, spontaneous dance breakdowns I've ever seen in a movie.

On the buzzier end of things, I caught a screening of Titane before the festival. I think I'm more lukewarm on it than Maxwell was—I'm not one to shy away from gore, but I liked it best when it felt the least rigidly symbolic and deliberately provocative. Mostly, it reminded me of how much I miss talking with friends and fellow filmgoers to help me process what I've seen. It's been interesting to watch the recent social media firestorm surrounding the film; it's certainly a conversation piece, but maybe not so conducive to that nuance-neutralizing forum.

Maybe this is a good year for NYFF to return to the three-dimensional world, and for festivalgoers to hash out these arguments over an overpriced IPA on some patio. Until then, these virtual Screen Slate pages shall suffice!