When I told a friend from Idaho that I was watching documentaries about regional black metal scenes in Europe, she said, “What’s black metal?” I laughed derisively. But then I thought about it. Why am I surprised that a millennial from the Rockies is unaware of a niche extreme metal genre that peaked in 1990s Scandinavia? Is my impression of this genre’s cultural footprint out of all proportion with its real significance? Do I have an unrealistic conception of its performers’ fame? I don’t listen to black metal or even know anyone who does, so why do I know about corpse paint, blast beats, and bands like Mayhem and Bathory? Reflecting some more, I realized that there’s one simple reason for my awareness of the conventions and iconography of black metal: Vice Media.

In 2007 Vice-owned VBS.tv produced a five-part docuseries called True Norwegian Black Metal centering on Gorgoroth. In 2009 and 2010 Vice heavily promoted Until the Light Takes Us, a documentary by Aaron Aites and Audrey Ewell about Burzum, Mayhem, and the murders and suicides among their members. Then, in 2018, Vice Films co-produced Lords of Chaos , a fictionalization of the story told in Until the Light Takes Us with Rory Culkin as Mayhem’s Øystein Aarseth. And since 2011, Vice’s music channel Noisey has published a lot of articles and videos on black metal: “We Hung Out with Metal Pagans at a Viking Cemetery,” “We’re Already in Hell, So You Might as Well Blast Some Evil Metal,” and hundreds more. To be fair, there are tens of thousands of articles on Noisey, but black metal still seems to occupy disproportionate real estate.

Although black metal subculture has spread to every corner of the globe and outlets like Noisey have gone to lengths to highlight its increasing ethnic and political diversity (with pieces like “Metal's Inclusive Future Looks Like a Zeal & Ardor Show” and “Riding the New Wave of Anti-Fascist Black Metal,” as well as articles about the local scenes in Saudi Arabia, India, Myanmar, and Bangladesh), its history is deeply marked by its origins in Northern Europe and its early ties to paganism, Celtic and Norse mythology, and frequent overlaps with white supremacist ideology. It feels like Noisey’s promotion of anti-fascist metal bands like Gaylord and Neckbeard Deathcamp and its publication of pieces like “Fuck Nazi Metal Sympathy” are intended to do some of the hard work of correcting co-founder Gavin McInnes-era Vice Magazine’s proto-alt-right editorial voice, part of the long process begun in 2008-2009 when McInnes was bought out and a member of Andrew Cuomo’s communications team was hired to help Vice rebrand.

But before Vice, the black metal phenomenon was being covered by people who were closer to the action: European TV reporters. And many of these TV reports and documentaries are available, free of charge, on YouTube.

From Norway, black metal spread south to the Netherlands, Belgium, and France, and with it media-fed fears about young satanists performing ritual sacrifice, torture, and arson. In Black Metal, a 1998 Belgian made-for-TV doc directed by Marilyn Watelet, we get to hang out with angsty teenagers in the small Flemish town of Ruddervoorde during a metal festival at a small local venue called The Rock Temple. The town is flanked by quaint fields crisscrossed by old men in tractors. Little Volkswagens and Peugeots putter past adolescents in corpse paint lining up to hear acts like Ancient Rites (from Flanders) and Dark Funeral (from Sweden). Teenage boys wear chain mail and dark cowls. There are also some hardcore guys who look lost. Almost everyone else is wearing a band tee sporting the symmetrical, barbed logos of bands like Emperor, Enslaved, and Setherial. One guy with a shaved head is wearing a shirt with a sun cross and “White Power/White Pride” on it. He looks confused, and maybe he’s in the wrong place, but as we’ll learn from some of the interviews that follow, these sentiments are more common than woke would-be-appreciators of black metal might hope.

For the most part, these adolescent metalheads act exactly the way you’d imagine: awkward, confused, and simmering with a targetless resentment. One boy says he wants to “transgress all that which is established.” Another confesses, “I had a difficult relationship with my father. That’s why I chose the Dark Side.” But some of them channel this nebulous anger in more clearly nationalistic and xenophobic directions. “Norwegian black metal bands go back to the vikings, because they’re proud of their ancestors, like us,” a guy says in Flemish. His bandmate puts it more pointedly: “Black metal is made for white people. Have you ever seen a n––––r at a black metal concert?”

It should come as no surprise to anyone even glancingly familiar with this scene that the infamous Varg Vikernes, part-time member of the seminal Mayhem, has become a committed Nazi since he was sentenced to 21 years in prison for the murder of his bandmate in 1994. The 1999 documentary Satan Rides the Media by Torstein Grude covers the early years of the second wave of black metal in early 1990s Norway, paying special attention to Vikernes’s crimes and the wave of church burnings that leveled 50 historic places of worship between 1992 and 1996. It’s structured as a procedural, following a cat-and-mouse game between Vikernes, a tabloid journalist, and the Bergen and Oslo police departments. It also highlights the role that the news media played in spreading the attitudes of black metal’s adherents. With spurious stories about secret satanist catacombs tunneled under churches and headlines like “I’m Odin and Satan’s Son and I’m Funded by the Ku Klux Klan,” tabloids fed the flames of the Norwegian public’s fear of — and fascination with — this transgressive phenomenon.

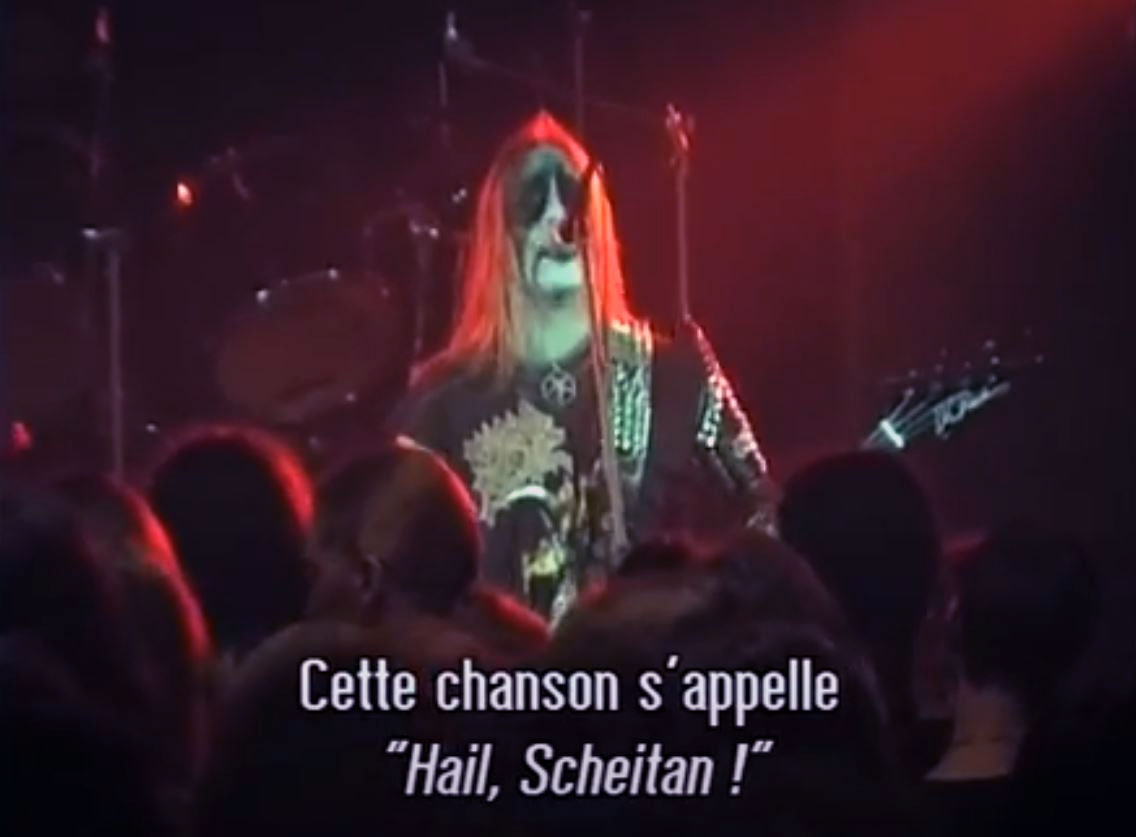

A great example of this media approach is French Métropole Television’s 12-minute feature from 2003 on the alleged spread of Satanism among France’s youth. We meet a young man who has bought a ceremonial dagger for automutilation purposes, a 25-year-old who lights black candles for magic, and a 17-year-old who brags about “sacking” 29 Catholic graves. The piece features Swedish black metal pioneers Marduk (whose lyrics and stated positions are explicitly anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim, and pro-Nazi), but also draws a spurious connection to the popularity of Marilyn Manson, whose pseudo-industrial shock pop has very little to do with black metal.

What emerges from these docs — as well as from Black Metal in Nederland (1995) and Det Svarte Alvor (1994) — is that for many black metal artists, a set of sincere nationalist and traditionalist beliefs are mixed with an ambiguously tongue-in-cheek fetishization of Nazi iconography, resulting in a theatrically transgressive posture that, in 2020, is inescapably reminiscent of the McInnes-founded Proud Boys’ brand of postmodern white nationalism.