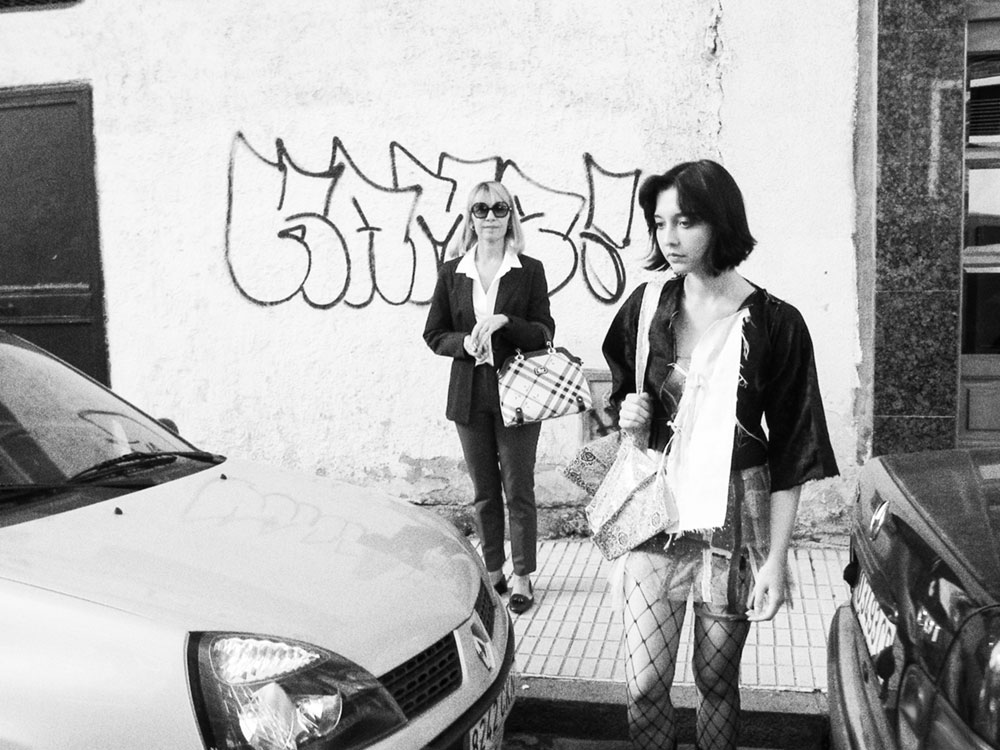

One of the year’s most outstanding debuts is Amalia Ulman’s El Planeta, her first feature in a career focused on a restless assortment of installations, net art, and performance pieces. Ulman plays Leo (short for Leonor), a designer who lives with her mother, Maria (played by Ulman’s mother), in Gijón, Spain, eking out an existence in a flat they can barely pay for. Mom keeps up appearances, with the odd scam or two, the two of them quarreling and making up, but despite their easy sense of style, they’re scrimping and barely hanging on. Elegantly conceived and with unfailingly sure-footed comic sense—both she and her mother are, not incidentally, note-perfect performers—the black-and-white film tells a story partly about precarity (of the sort countless earnest indies have attempted). As ever, Ulman is subtly sharp on how power dynamics are deceptively fluid. One of her most famous pieces was an Instagram work, when she created and performed multiple attention-courting personas in the app’s earlier days.

Based in New York, the 32-year-old Ulman grew up in Spain but her parents are Argentine (and hipsters, in her words). I talked with her about the rich nuances of El Planeta—from the particularities of its Spanish calculus of class and identity, to the thinking behind its look—as well as her artistic practice, labor, New York, and not being a Zoom messiah. El Planeta had its world premiere at Sundance, which is how I originally saw it, and it screens August 27 as part of Rooftop Films, with Utopia handling its September 24 theatrical release.

How do you describe the movie to yourself? Part of what I love is that it’s hard to pigeonhole.

I think of it as a dark comedy. I like the logline “a comedy about eviction” because it’s a contradiction of sorts, because of the subject matter. I think it was important to me to tackle that subject with a little lightness.

How was it working with your mother?

It was super easy to collaborate with my mother because she was acting in the film. That’s not how she is. She always helped me with my art projects a little bit behind the scenes, but she could never properly collaborate because she doesn’t know much about fine arts. But she does know a lot about movies. She took some acting lessons and read all the Strasberg books and had a lot of different references for putting together her character. Obviously a lot of it came from Grey Gardens and things like that. The only part that was hard was revisiting certain painful moments from our past or having to reenact the fight, which she didn’t want to do. She enjoyed the more comedic aspects of the film.

It’s a wonderful performance, not only the comic moments but also things like when she’s on the phone talking about being homeless, really a challenging monologue. What aspects were particularly hard to do?

Well, we did lose our home, so that is one of the things that we used as fuel for our performances and also the arc of the story, to be able to make something that was truthful to going through something like that. How one can go from being a so-called normal person and suddenly having to deal with homelessness. Which is obviously very shocking for anybody that hasn’t been homeless for a long time. It’s a gradual process. It’s not something that happens overnight. And it can be very stressful and damaging for the person going through that. So that was something that we used for the film and the characters and also to be able to tackle it with more humor. Because we could do that. We didn’t have any guilt or detachment from the subject matter.

The movie is so remarkable in having a light touch while chronicling tough moments. Like the scene in the beginning when your character is meeting a guy (played by director Nacho Vigalondo) about getting paid for sex. It’s sort of funny but also she’s in a tough spot. And then you end with a little Buster Keaton shrug.

All of that is very intentional. I think it was very important to set the tone, because people, especially from big cities or richer countries in general, forget that it’s one thing to hustle in a place where you might be surrounded by richer people, and another thing trying to hustle when you’re trapped in a small city. If you’re doing something like sex work, the pay is so, so low. It was a way of showing how trapped the character of Leo was in that situation. I know that a lot of people in big cities are able to do that, mingle with the richer people or have friendships with people from different classes. But what happens when you don’t have access to that even if you wanted to? What else would you do if you couldn’t even do that? So I think that helped set up the framework of how hard it is for these characters to survive.

You also show the characters working around class boundaries. The mother has all these techniques for getting a free meal or a nice outfit. And there are details with your character, the elegant euphemisms when talking to the magazine editor who wants to hire you, because she knows he wouldn’t get or accept her situation.

Yeah, that was a very important part of the movie. One misconception about the movie by people that don’t know Spain very well is that the characters used to be rich, or really rich, or something like that. And that they’re clinging to that lifestyle. But actually the character of the mother—which denotes the upbringing of Leo—is that they’re conservative Spaniards. And in Spain, there are two Spains. You have the right and the left. Right-wingers—and this is something that as an immigrant I’ve always been fascinated by—keep up appearances and dress posh only because of their politics. It has nothing to do with their actual income or anything. I’ve met plenty of fishmongers that work at a supermarket who dress in Burberry and Lacoste because of their politics, not because of their money. And then you would find an old family of socialists that has gone to college abroad and they don’t dress like that because of their politics. They dress like from Zara or whatever. That’s something that is very particular to Spain. Posh people would send their kids to so-called private school, which is not really “private,” it’s just Catholic. That’s where they wear the uniforms and everything. The cost of sending your kids to Catholic school in Spain is very low, like 20 euros a month. So it’s not about monetary access but politics and beliefs. I went to regular school—atheist school—the state one.

I’m fascinated by that sort of class, clinging to those ideas which are related to old colonial Spain, despite not being real anymore. It’s not really that the characters had been rich—I mean, maybe if we are talking about Spain [generally] being a colonizing power, but that was hundreds of years ago. So it’s not like a movie like Blue Jasmine, for example, where the main character was actually wealthy. In this case, it’s more like they’re keeping up appearances, because that’s what goes on in their whole lives as Spaniards—and it’s such a brittle existence that something little happened and now they’re homeless. And obviously the wife has always been a housewife, she never had a job, which is very, very common in Spain of that era. That didn’t mean they were privileged, that’s just sexism. [chuckles] Women stay home taking care of the kids, that’s all. When something happens, you are left alone without any sort of security or access to any sort of welfare.

So in that sense, the idea of class “passing” is a bit more nuanced because of the setting. It doesn’t have much to do with how you are portrayed in the U.S. or anywhere else. It’s particular to that notion of how people dress for their political views in Spanish which has a lot to do with the royal family and being posh, And British culture and dressing in Lacoste polos...

The badge of respectability.

Yeah, it’s more like decency and respectability.

I read one description of the movie that confidently said it’s set in 2009, is that right?

It’s not really based in a particular year. If anything, it would be whatever year Scorsese went to the Gijón festival [a visit that keeps getting referenced during the movie], 2018 or something like that. Basically, the city and Spain in general got stuck after the 2008 crisis and never fully recovered, especially smaller places. Everything that is depicted in the film could have been anytime after that crisis. It got stuck in that bubble of time. Obviously with the pandemic it hasn’t gotten better sadly.

You show regular shots of storefronts that are closed or for rent.

Yeah, it’s also the perspective of their existence. Those stores are there, they’re empty, but you especially notice them if you are looking for a job. I know that feeling of looking for waitressing jobs or some small thing, and you see all these restaurants closed down. You become more desperate because you have fewer and fewer options. So that also heightens what they’re going through. A lot of people from my city haven’t even really even noticed because they have stable jobs. They’re not paying attention as much as anyone that is trying to survive.

Talking of perspective reminds me of a particular shot you use in this film: these inserts of silent reaction shots.

[Brightly] Oh yeah!

They remind me of shots in silent movies. What was the thinking behind those?

Yeah, it was a version of that. A lot of inspiration for the film came from really old movies. I knew that either way I would include those references, they would turn out to be something new, because the distance from it is so huge and obviously we’re not in 1920s costumes or anything like that. But I’ve always liked those close-ups of people’s reactions to someone else. We introduce that in a bit of a new way, but it definitely comes from those shots of an emotional response to something that’s happening, that is very particular to that era.

What was your approach to the look of the film? Did you ever operate the camera if you weren’t in front of it?

I had a great DP, and I just let him do his thing. I prepared shots in a way that was already photographic. I planned every scene and under that direction, the DP did his own magic on it. Generally I’m behind the camera for artworks and things like that.

How did you connect with the DP?

I haven’t lived in Spain for a long time, so it was a bit hard to find a Spanish crew, but from all the people that I saw, I saw this movie that he did, Yo La Busco, and it looks beautiful. He made that film with a simple DSLR. So I thought if this guy is flexible enough to do his thing with DSLR he is a perfect candidate to use a Black Magic and be creative about the use of camera. We had a very limited budget so I really needed to be able to trust somebody that I knew was resourceful. And that was the case.

El Planeta has been compared to independent movies in New York in the 1980s and early ’90s. That made me think of something else about your movie: you’re playing an artist, but you’re not ironic or romantic about the economic situation.

Right. I feel like the one person that does that in his films from that era would be Hal Hartley. There are a lot of plumbers or something who have artistic inclinations. And I always appreciated that. I’m lower class myself and then through grants or whatever I was able to make art and go to art school et cetera. But it became very obvious when I went to London that the class divide was huge. All these people I was surrounded by were really, really rich. So it was a bit of an unhinged situation navigating gallery dinners, museum dinners, et cetera, and talking with collectors, and then going back to my reality of being hungry. That didn’t diminish my capacity as an artist. I was still the same artist. It was this idea of, who is allowed to make art, who is allowed to be eccentric.

I feel like when people are portrayed in contemporary movies about poverty, everyone is very nice, very humble, and they just want their little job and don’t bother anyone. I think that’s what the upper classes want. They have that sort of idea of poor people as people that don’t want to bother anyone and are humble. I don’t think that’s the case and that sometimes poor people are extremely fascinating and talented and funny and witty. So in that sense, I feel like 1930s movies are much better at reflecting that than current movies. But when times are better in general, there’s more opportunities for people from lower classes to make art, and I think that gets reflected in culture. When everything goes bad, only the very very rich people are allowed to make art. I think that changes the landscape a lot. I don’t know what the situation was with these movies in the 80s and 90s in New York, but there’s definitely more of that.

How does it compare for you as a working artist today in New York?

New York, hmmm, the thing is... In Spain I was already an immigrant and I never really had deep roots there. My situation was so fucked up that I had nothing else to do but to leave. I had nothing to lose. So I aimed higher. [Laughs] Which I think is the case of a lot of people that I know in New York, you know? It’s people that are here because they have nothing left to lose. But in a way, New York is a great home to this kind of people. And always has been. So in that sense, I love big cities, and despite my disability [from injuries sustained in bus crash in 2013], I love walking around and seeing things and stuff. I go out every day and see the city.

I love New York! It’s the best feeling. And it’s a very inspiring place and most of my friends are here, and you have that energy I think that makes it worth it. There’s a lot of movement, and there’s a very strong sense of community. In terms of being able to afford it or not, I mean, Berlin used to be cheap, it’s not anymore. Los Angeles is as expensive as New York, it’s just the spaces are bigger. London is over because they left the European Union. So yeah, compared to many other places I’ve been to, I feel like there’s more opportunities as well being able to afford it. I feel like that’s how it feels for me and my friends. If you love New York, you’ll do everything to stay here. Of course, I guess I could be able to afford to mortgage a house in Kentucky. But I really don’t care. I would rather die renting in New York than... I dunno, living in the middle of nowhere. That’s just me. I guess it depends on what kind of art you make. I like the noise of the city.

Speaking of your art practice, what has the past year been like, as a pioneer in net art? Has it affected your perspective, when so much had to take place online?

I mean, it was so, so stupid, that whole thing. A lot of people came running to me desperately at the very beginning of the pandemic, like, “What are we going to do? Tell us what to do!” For free, obviously. With zero funding and really limited ideas of the internet. Oh, let’s do all these letters on Zoom. And it’s like... no. I’m not the only one who dealt with that. A lot of net artists dealt with people asking them, “What are we going to do? Now is your time to shine.”

“Lead us!”

Yeah. So that was a strange moment of desperation from a lot of people. My interest in any of this has been through my interest of how people present themselves and interact with one another and appearances and class. And that obviously had reflected in Instagram and other things. That’s the only reason I was ever attracted to it. Otherwise, each artwork that I make requires different disciplines. I also made a lot of installation and video work. I have a long series of video essays that I made with PowerPoint presentations—which influenced the movie, because of the transitions used. I feel like I respond to different things, different times.

It was funny to have people being so crazy about trying to make things work. But I think it’s always from the wrong perspective of trying to replace the real world. And I think one of the reasons my first performance was successful was because I was using the language inherent to the internet instead of trying to replicate anything else. It was working with that place in our brains that generates stories without us knowing about it even. That sort of dumb scrolling... I was not telling anyone, I was not explaining what to look at, I was just using the internet the way it’s naturally used. And I feel like in a lot of these cases, people were just trying to replicate all these things. A Zoom Party is not a fun party.

Become a Zoom consultant sounds like a nightmare.

When anyone wanted to approach me, I was like, “That’s a terrible idea. You should go away on holiday and come back.”

What’s the biggest difference between filmmaking and gallery art or net art, formally speaking? Is it partly how each form structures time?

For me it’s a very simple answer: legal paperwork. It is really restricting for an artist. In art, a lot of those things are absolutely neglected and no one gets credited for anything and there are no unions. In film, everything needs to get accounted for and everything has to be papered. And I actually think that’s great. It’s really good that if you’re creating this vision and you’re using other people’s artistry, whether it’s their music or whatever, they get credited or compensated in some way. Which in the art world is not even considered. No one gets credited. That’s why art videos don’t even have credits at the end. It’s not because no one has worked on it, it’s because no one cares. It’s this idea of the genius master that is the only name that gets credited, and everyone else is like...

So that was a big learning experience from working in film. All the crew came from film backgrounds, so they took their breaks religiously, their lunch, their days off. And that was fascinating for me because I never got a lunch break. Ever. Working, setting up a show, anything—I never got a lunch paid that was not a gallery dinner. You couldn’t say, “I’m going to rest today. I’m still getting paid, of course.” People would be like, what? So for me that was a big difference. The changes in structure were in the way you work. Because in the art world, people make films with a lot of appropriated material and they take from here and here. And film creates a different workflow.

How many shooting days was El Planeta?

Seventeen.

I know you’re doing different work these days but how does creating Instagram pieces compare with shooting a movie? Did you shoot the Instagram images at once?

Yeah. Originally, when I was still testing things, I was performing here and there [while working on a piece], but it was very distracting. So what I would do is that I would go into character for two or three days in a row and create all these photographs that I would then upload when I was not performing. I had an archive of videos and everything. So in a way it was pretty similar to working in a film: a pretty intensive workflow and then you organize and you edit it. The shooting times were very intensive, and then there was a lot of time to decompress, edit it, all that stuff. Obviously working from a sort of script, creating all these costumes, and finding a location—in that sense it was a bit similar.

It’s easy to forget how artworks like the Instagram pieces can be created in a compressed manner but the presentation, the construction of the piece in time, is a different thing.

Right. Which is how a lot of girls do it, a lot of influencers. They do shoot a lot of stuff and scout locations, and everything is very prepared. It’s not like, “I’m just walking around and took a photo.” There’s a lot of editing. This was very early on [with my projects], so people weren’t expecting so much editing, and then it became normal because influencers became professionalized. And they had to deliver all this content and stuff. and it changed how people originally used it, which is you take the picture directly from the app and you upload directly from the app, and there’s barely any editing and it happens in the moment.

It makes you think what “live” is. It becomes in this case the quality of liveness or recent-ness. It’s almost another color, how immediate something feels is. The tense of the picture.

Yeah. I mean the one reason that I became fascinated and wanted to do that first project was because I had seen a lot of girls very carefully choosing the mirror where their pictures are taken. They would go out to hotels and things like that. And those were definitely not their homes, right? So they were creating this idea of class through their social media. Because a lot of them were sugar babies or whatever, so they had to have this image of how they deserve luxury from sugar daddies. I thought that was very fascinating, how that became another accessory for a lot of girls—the way they typed online.

I tried to read very little about El Planeta before watching it, but afterward, I saw people say the movie was based on a real-life mother-daughter grifter team. How much did you actually draw upon that idea? I didn’t feel I needed the reference point at all.

Yeah, that sparked the original drive to make the film, but not because of them per se. What they did is pretty simple. There’s nothing spectacular about it. It’s just two women that pretended to be rich and ate for free at restaurants. And it ends there, you know. What was fascinating to me was how that story was a portrait of the town more than like themselves. Because it was such a ridiculous scam that it’s the kind of thing that could only happen in that sort of town where I’m from and not somewhere like Buenos Aires or New York. So I thought that was very funny how these women got away with it because they’re Spanish and they can do that, but me, as a foreign South American can never do that, or any other immigrant in Spain, because they could not pull that off. So that part for me was fascinating. That it would be so simple to trick people because there are so many people that still live in Spain from old titles, like royal titles, that don’t translate in money anymore, but a lot of people have these connections, et cetera et cetera. It’s representative of a very old Spain that’s still there. And that’s pretty much it. Everything else [in the movie] is more of composite of my and my friends’ lives and anecdotes and things like that. Very little was kept from those characters [the grifters].

For you personally, you identify as Argentine?

Well, I definitely grew up in Spain but, being an immigrant in a small town in Spain where there were no foreigners at all, all my attempts to be Spanish weren’t too successful because everyone would remind me that I was foreign all the time. There’s not much of an awareness, like in America, of being American while being from another culture as well. So even today, I have those limitations when I meet people because I look too exotic for them or my name is not the typical Spanish name and everyone’s confused. I grew up in Spain like any other normal Spanish kid so I’m very aware of the culture, but my parents are very Argentinian and my cultural baggage is Argentinian. My grandma is indigenous from the north of Argentina and all that stuff is like Argentinian history, not Spanish. So that’s there, too. [chuckles]

I recognize some of this because my parents were not from the U.S. And growing up, things always felt a little bit different...

Yeah, you know, it’s always like... that little thing.

And your parents were hipsters?

Yeah, they’re Gen-Xers, my dad is a punk, my mom is more like “indie.” I grew up surrounded by that which has a lot to do with appearances. I remember my mom crying when Kurt Cobain died. And they paid a lot of attention to how they presented themes within a community of underground, whatever. You had the mods and the rockers and the punks and the this and the that. And everyone had to have the right jeans or the right boots and all that stuff. That’s sort of where my interest in fashion comes from as well, being surrounded by this constant attention to detail for all these very stupid things. But yeah, that says a lot about my upbringing because there’s not that many people that I’ve met that had that experience. Personally, that’s why I’ve been very suspicious of appearances in terms of subcultures, or trying to defy the system by dyeing one’s hair green or something.

And that makes my background a little weird, because we were immigrants and we were poor, but we were not the regular kind of immigrants. So some of my experience was immigrant experience—of sending money to my grandma on Western Union, or calling my family from those old places that used to have phones, you know, especially for immigrants. So that’s one side, and the other side of my experience is my parents trying to get into a Green Day concert when I was a baby. My dad used to have a skateboard factory in the ’80s in Argentina, and I’ve always been surrounded by that. They’re the kind of people that would read the original Vice magazine, that sort of sense of humor. And that’s why I’m kind of over that, because that’s my parents. Johnny Knoxville kind of stuff. Which is funny, because it’s not most people’s parents.

Where does the freezing curses thing come from? In the movie your character’s mom writes curses on slips of paper and freezes them.

That’s a common little housewife trick thing. My mom does that for real. I don’t know if she got it from a Cosmo magazine or something like that. But then many girls contacted me after seeing the film, telling me that their moms would do the same. I don’t know, it’s like something happens to moms’ brains under too much time alone in their kitchens, and they start doing these things. So yeah, that’s a real thing. I doubt it does anything.

Doesn’t hurt, I guess. But it’s another sweet detail about the mother in the movie. I haven’t really asked about the small romantic arc in the movie (with a guy who’s taking care of his family’s store), maybe because I think the true romance is between you and your mother.

I think that was very intentional that all the male characters were secondary to the love story between the mom and daughter, which was the main part. Yeah, I feel like the film has been criticized for having shitty male characters. Um.... but I feel like that was not intentional. The people who worked on the film were men—it was not an anti-man film in any way. But I think it was also a response to the energy that these women were putting out there. Because in their desperation, all their relationships were transactional. And that can never end that well. So that’s why there is so much disappointment. It’s because nothing that they’re doing with men in particular is a genuine connection. It’s more like I’m counting the minutes that I can monetize this because I’m desperate. And that’ll never work for anybody. I don’t know how it works, if it’s the energy or the chakras or whatever. But also when one is in that situation, the worst kind of people come to you because they smell the desperation, how they can abuse that.

To end with the credits: there’s TV footage from the Gijón festival, including people on the street getting interviewed. Is that your mother in one of those shots?

Yes. That was a lucky moment, where the actual prize ceremony that is mentioned throughout the script happened on the last day of the shoot. There were a lot of police that year because the younger princess was attending and a lot of people wanted to kill the king in Spain. So it was impossible to bring a crew. But we thought, let’s have her in character and hope for the best. Her charisma attracted the cameras and she was on TV, and we took that footage!