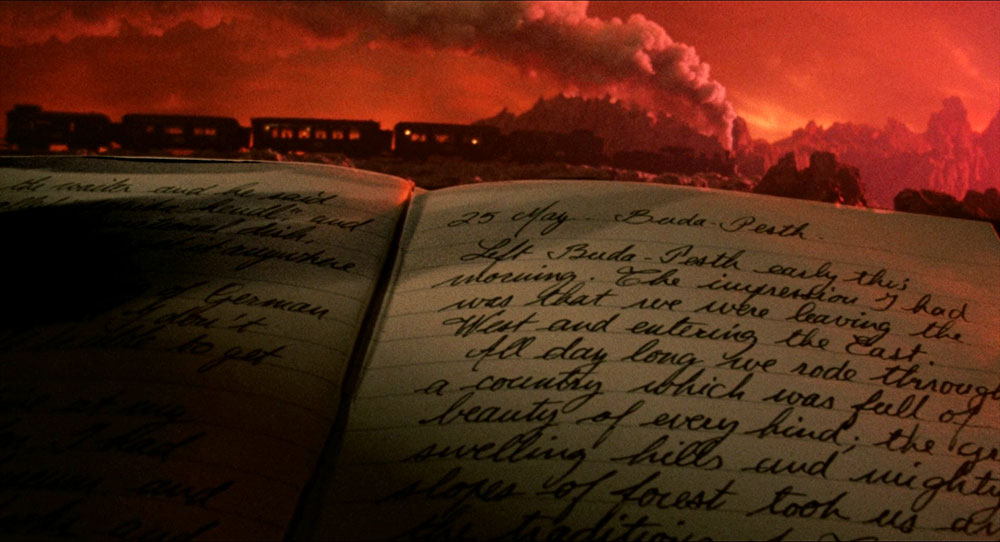

Long considered an outlier in Francis Ford Coppola’s filmography, the auteur-cum-vintner’s 1992 adaptation of Bram Stoker’s Dracula has ripened, some 30 years since its release, from splashy studio release into a masterpiece of gothic horror. The follow up to The Godfather III (1990) harkens back to the director’s salad days at the knee of Roger Corman, stepping in to helm a seemingly random assortment of horror cheapies. For all its elaborate bluster, Dracula hews closer to the esprit de corps of American International Pictures’ efforts The Tower of London (1962) and The Terror (1963), marking a return to form of sorts for Coppola after years spent dabbling in prestige studio filmmaking.

From the sanguine first moments to the spectacular climax, Dracula revels in its timelessness, conjuring decades-old effects techniques back from the dead. Unleashed during a brief vogue for vampire pictures that began with the twin 1987 releases of Lost Boys and Near Dark and concluded with Interview with a Vampire (1994) and Dracula: Dead and Loving It (1995), Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s straddled an uneasy line between operatic, Grand Guignol camp and straight-ahead studio seriousness, wedding hypersexualized ’90s erotica with a deep reverence for Old Hollywood craftsmanship.

Under the guise of “research” for my own forthcoming film, one muggy evening I finally surrendered to a first watch. From the first moments of that blood-spattered prologue, I was rapturously engaged, and by the time the credits rolled I was thoroughly in its spell. A condensed account of Vlad Dracula’s 15th-century origin story—silhouetted crusader carnage, a blasphemous church harikiri set against towering Gothic interiors—kicks the film off on a high, high note. Dracula is more than mere spectacle: it represents a welcome antidote to pervasive, labor-abusing, sportsmode CGI, a sinister transmission from a bygone era when astronomical budgets bore their fruit onscreen.

Combining camera trickery with turn-of-the-century illusions, Visual Effects and Second Unit Director Roman Coppola—son of Francis and, later, director of indie masterpiece CQ (2001)—devised a magician’s bag to set this entry apart from its blood-sucking contemporaries. Determined to uncover the rich history of this project—and pick up a few tips myself—I made like Jonathan Harker in the backwoods of Transylvania and sought out Coppola the Younger. After a very polite exchange with his assistant, I passed along the below questions. Roman replied in a series of mysterious voice memos, the transcript of which has been edited for maximum clarity of vibe.

Caroline Golum: Upon recent viewing, this film has aged spectacularly. The effects look fresh and exciting. How do you feel about the film now that 30 years have passed?

Roman Coppola: I am very proud of the movie; it's fun to see that it's endured. And I do think that the way we approached the effects, with more classic techniques, gave it a certain longevity. Those techniques are tried and true, and had an appealing, integrated quality that, obviously, really suits the movie. The film was set in 1897, and that was the birth of the cinema, so many of those tricks were developed during that time. And so it all feels as a whole, which is credit to my dad's approach of making it with the techniques that would have been used at that time. Now that 30 years have passed—it's hard to believe, to be honest, it has really been that long—I look back with fondness. It was my first directing opportunity, and it was very formative.

CG: Practical effects are increasingly rare, and much of this knowledge is obscure or arcane—trade secrets lost to time.

RC: It's true that these things are less and less familiar, but there are a core group of effects that remain in use. You see a TikTok video where someone pops out of frame and pops in—that would be a use of a jump cut. Many of these tricks were beautifully done in the past by artists like Georges Méliès and others. I was always interested, as I did my research, in the birth of cinema. There was “documentary”, in which you're someone just rolling the camera, and seeing a train go by or street scene. And then, very soon after, there was what was known as a “trick film,” of which Méliès is the most appreciated proponent. Early on in filmmaking, using camera trickery was very popular, very novel, and very beloved.

So many of those techniques we ended up using in terms of being arcane, or so on—if you poke around the internet, there are people who do wonderful visual effects in-camera, as we did: forced perspective, shifting gravity, jump cuts, running film backwards, these kinds of core techniques that continue to be used. Some of the more tricky techniques are specifically the use of matte paintings, which takes a lot of skill.

There are two categories of general camera tricks that continue to be used and are quite well known, and then a few more obscure ones that we were able to do: specifically, latent multipass images—the same camera negative exposed in the camera multiple times, getting new elements that combined in the negative. We did this with the latent and matte paintings, which was rather tricky to the very expert matte painters that we had—Craig Barron and Michael Pangrazio, and others who executed those paintings. We did some other multipass images, which basically means we made multiple exposures in the camera by re-exposing the same film over and over. And that was pretty cool, pretty rare.

Certainly, nowadays, it would be quite uncommon to combine images with that commitment on the original negative since it's rare to shoot film. When images are combined on the same camera negative, they behave in a much different way than when they're combined in post production on digital. For each element that's illuminated it exposes the film, things stack up in a much more organic way, in my view, than with digital compositing.

CG: What was your process like developing the effects in this film? What research did it entail?

RC: Well, I did a ton of research. There are a lot of books that I collected. [A selected bibliography shared by Coppola is available to our Patreon supporters. –Ed.] I am really pretty proud of my little library we built for the movie. We went in and found books that were available, but also other articles. I found a neat article that was written by Gregg Toland, who, of course, is the masterful cinematographer of Citizen Kane [1941], and he spoke about some of his techniques of extreme deep focus and some other lighting techniques.

It was long after the heyday of the visual effects that we were referring to, which was the ’20s and ’30s and ’40s. But, you know, 1992 wasn't that far away. There was a little bit more of a contact with those artists, certainly matte painters. We always tried to do things in camera on set, but there was a lot of work that was done on an optical printer, and that's something that really truly is extinct now. All effects are done digitally. I remember when, not so [long] after we finished up that work, most of the shops took their optical printers and put them out in the parking lot, and they were just rusted out. There can't be many optical printers left. Certainly the expertise and the artistry that we were able to tap into does not exist any longer.

CG: Did you speak with technicians who had worked during the “Golden Age” of Hollywood cinema?

RC: There was a big team of people, we had a lot of different effects companies and folks that did miniatures for us and different things, with a lot of affection, as well as the great Gene Warren, Jr., who led the way on many of the really fun, cool effects that we did. And Linwood Dunn, who's a legend. We tapped into all the skill and talent of the matte-painting world and the miniature world. These kinds of businesses did have that conduit to the past. Those folks had lineage that went back, for example: Gene, from Fantasy II Film Effects. His father, Gene Warren, Sr., had done miniatures. But beyond that, we were reading, learning, and just doing our best.

CG: Were there periods of experimentation, testing, proofs-of-concept?

RC: Luckily I was very involved with the preparation. I helped with the storyboarding. And so, as we were boarding, we were figuring out ways that we could employ certain techniques. I'll tell a little anecdote: when you do a multipass image—meaning you run the film, and then you roll it back, and you run it forward again—you have to have very good records of what occurred at what place and very good notes because, as you roll it back, you have to sync it back up again. And we did have an occasion where we shot forward on a roll of film, we wound the film backwards, and we rethreaded it through to re-expose it again. But we were off a perf, meaning a perforation became maladjusted. Basically the shot was ruined, because we didn't have absolute precision getting back to that exact start point. That's part of the price of admission, you know. You're doing things this way, in camera, you just have to be willing to accept that there are going to be errors and difficulty.

My dad was very gracious and very excited about what we're doing, so we had total support. We were shooting in the MGM studio, which became the Sony lot, but it had an incredible history. There was a feeling of exploration and being able to learn and to fail at times; we had that luxury, which is not so common in many films.

CG: Were there particular effects or techniques that were easier than you anticipated? Or harder

RC: Each different technique had its own challenges. One that was particularly hard, just from a mental place, was a shot where some green mist comes up into a bed where Mina is sleeping, it's Dracula taking shape, shifting into a misty form.

What we did, which was really fun, is we had two sets, side by side at 90-degree angles, and we had a mirror. By shooting through the mirror, part of the image was exposed when we saw it through the mirror, and part of the image was reflected in the mirror. So the two sets were combined. We had a whole set that was basically a replica in black velvet, and then we had smoke that we could control—dry ice with tubes and different little ducts and some fans to guide it so it could kind of go under the covers. We had a puppeted cover that would go up and go down and so on.

But the confusing thing is, we're doing all that, and I'm pretty sure we ran it backwards so that the smoke had that kind of eerie, backwards motion. We start combining mirrors and backwards action and smoke and stuff. I remember [thinking], “Jeez, I hope we're doing this right, too.” We used this kind of Pepper's Ghost—that was a fun one that worked out; that was rather complex for sort of a simple image. But those are the kinds of things—running film backwards using mirrors. . . . To remember and recall how things should be performed backwards is just one more element of the puzzle.

CG: Technology has altered filmgoing: streaming has expanded access to heretofore underseen gems; CGI has become more pervasive across movies, television, even ads. Have we reached peak CGI, or will we ever?

RC: I don't think we have reached peak CGI. There inevitably will be incredible further advances, and it's hard to imagine. But I think computer-generated images are definitely here to stay and hopefully to be used in an inventive, creative way.

CG: Do you anticipate practical effects having a renaissance as bad digital filmmaking becomes more commonplace?

RC: I sure hope so. I think for the right project, practical effects are very suited: miniatures in big movies will continue to be used for things that are hard to replicate. And I think we see in this kind of TikTok generation, younger people using some of these classic effects. So hopefully, there'll be a continued appreciation for some of the “naïve” or classic effects that we all admire.

CG: There are obvious comparisons to be made between Bram Stoker’s Dracula and the influence of German Expressionist filmmakers in the early 20th century.

RC: In addition to the German expressionist movies, John Cocteau was a particular influence—specifically Beauty and the Beast [1946] and Orpheus [1950]. Beauty was a big point of inspiration, with a lot of wonderful illusions that were built into it.

CG: Where else did you seek inspiration? Were there paintings, books, objets d’art, or other media you were looking at during this process?

RC: We made a show reel. Back in those days things were less available, of course, [without the internet and] YouTube and that type of thing. So we had a library of movies that were points of inspiration. And the one that stands out is Beauty and the Beast as I mentioned, but also Blood of a Poet [1932], which is another Jean Cocteau movie.

CG: Mainstream movie budgets seem to grow bigger every year, but you never really “see the money” on screen.

RC: It is remarkable to think that certain movies, whether it's Lawrence of Arabia [1962], or even Apocalypse Now [1979], are these very big-scale images, movies from the past. If they were to be made today, the costs would be, I'm sure, quintupled or something. And it's hard to understand, especially with the advent of certain technology like cell phones, that all the locations were photographed with still cameras; they sent the film to the labs, and anyone who saw it had to be sent a physical copy.

The efficiency we have now with digital technology, whether it's research or sharing media, is far superior, and yet it's odd that the cost [of film production] remains incredibly high.

CG: As a filmmaker with a career very rooted in the physical/material, how do you reconcile your expansive vision with material constraints?

RC: Well, that is always a trick. You know how to realize things for a “responsible budget.” There's fun in trying to invent images that use trickery, or adapt things, or suggest. A lot of my background comes from the second unit, where if you have to use limited scale—like say you need to make an impression that someone is in a more vast location by suggestion; with water reflecting or sound effects or whatever you can suggest a much bigger scene that isn't actually there using imagination. That's probably the key to much interesting filmmaking: how the filmmaker engages the audience's imagination and makes them see things that maybe aren't physically there.

CG: I absolutely adored CQ when it came out, even bought the 2-LP soundtrack. It arrived at an interesting moment for independent cinema, with an aesthetic looking back at mid-century utopian design aesthetics. What drew you to that particular style? Is it something you still gravitate toward?

RC: My story is that I was turned on by a friend, a musician. We did a video for it. He told me to check out Danger Diabolik [1968], and it just really hit the spot. It was so playful and colorful, and I'm a fan of comics. I should actually make a shout out to Mario Bava, who is also a master of filmmaking, but with deep knowledge of visual effects. If you look at his movies, including Danger Diabolik, he used miniatures and was incredibly crafty, probably more than any other filmmaker I can think of. Because he was an effects expert and cinematographer. So his works inspired me, but yeah, I love that time and place. It really was a love letter to cinema, and I tried to evoke some of my early memories of being around my dad, his cohort and buddies, making work and how that impressed me. So that early memory of 1970, when the film was set, means a lot to me.

Bram Stoker’s Dracula screens on 35mm October 19 and October 21 at Roxy Cinema, and was also recently reissued on disc and select cinemas in a new 4K restoration.