What is an anarchist film? The easiest answer, “a film made by an anarchist,” is unsatisfying and insufficient: films are collaborative undertakings, and so never truly beholden to the vision of a single individual. And anyway, anarchism itself is infamously hard to define. It means rejecting the state and capitalism, but beyond that, no two anarchists are likely to completely agree. Anarchism has no canonical texts, no single tradition. Combine that with more than a century of popular slander, and anarchism can be a very difficult thing to pin down.

But this definition trouble also reflects a core strength: Anarchism is a living tradition that tends to evolve and transform directly in relation to social struggle and practice. Anthology Film Archives’s online series Anarchism on Film, organized with Richard Porton and running now through February 16, most of it screening for free, highlights connection to lived struggle as perhaps the crucial aspect of anarchist filmmaking. All of the films in the series depict rebellion, insurrection, organizing and/or revolution in some form. As a whole, the series offers a somewhat scattershot but fascinating glimpse of filmmaking styles and struggles, while putting forward a tentative thesis about what “anarchist film” might look like.

Maple Razsa & Pacho Velez’s 2010 Bastards of Utopiais a documentary following three anarchist organizers and activists in Croatia circa 2003-4. The piece captures a movement in decline, the tail end of the “alter-globalization” and “summit-hopping” era. We see one of the many days-long internationalist gatherings of resistance and riot attempting to shut down global economic forums, conferences, and summits like the WTO, IMF, or G9 that made the movement’s core. We also see the three organizers’ context at home, as they struggle in the face of a hard-right, nationalist atmosphere after the Yugoslav Civil War. Eventually we see their collective dissolve when a squatted free store they are running is raided by police. But anarchist film tends to refuse elegiac and mournful modes, insisting on the continuation of struggle in the present: Bastards follows up with its three organizers in 2008, as they have continued to organize and fight, now in different cities and different ways.

The Old School of Capitalism picks up historically where Bastards left off, mixing documentary and reenactment to focus on a period of explosive workers’ revolts in Serbia in 2008/9. The collapse of state communism led to capitalists in the 90s and 2000s stripping economic infrastructure for parts across the former-USSR, emptying factories and decimating employment. These tendencies came to a disastrous head in the financial and economic collapse of 2007/8, and a wave of struggle emerged in response. While some activists interviewed in the film want a return to state socialism — another typical feature of anarchist film is giving space for the arguments of anyone present on screen — the film mostly follows a group of workers engaged in escalating direct action to try and get two years of back wages stolen after their factory is liquidated.

They squat the now-empty factory, get in shoot-outs with the bosses, knock down one of the buildings and redistribute its bricks amongst themselves, all the while arguing about tactics with a group of young anarchist activists who’ve joined them in solidarity. The film features the protagonists of this story — actual workers and activists — reenacting and creating a version of the struggle they’ve just taken part in. Intercut with documentary footage of mass demonstrations, the film allows conflicts with the bosses, other leftists and one another to play out and remain unresolved, showing how difficult and disorienting social movement and class relations are in the wake of both Communist totality and capitalist dreams: all the old scripts feel useless, but new ones have yet to be improvised.

Both of these works capture a particular moment aesthetically and culturally: shot on cheap handheld digital cameras, with a distinctly DIY aesthetic, these video documents have a kind of rambling looseness to them. The aesthetic shifts a bit for Razsa & Milton Guillén’s 2017 Maribor Uprisings: the digital cameras are better for one thing — there are drone shots! — and the filmmakers have created a branching choose-your-own-adenture docudrama. At screenings, they would change what they showed depending on audience response to prompts embedded in the movie, meaning no two screenings were exactly alike (an experience not available under COVID-19 digital-festival conditions). Cutting together documentary footage of two massive uprisings that shook the city and all of Slovenia in 2012-3, they create a third, fictional uprising in Maribor, place viewers on the street beside the camera crew, and ask them to decide and debate what level of action they are willing to take and which camera/activist they will follow. The film acts as an interactive essay and consciousness raising session about the questions of non-violence, direct action and repression in uprising, while giving the audience an experience of indirect participation.

As levels of social struggle increased dramatically in the years between 2008 and 2017, so too does the tactical urgency of the questions being asked and addressed. While the audience of Bastards of Utopia and The Old School of Capitalism are outsiders and the films depicts people trying to figure out how and where to begin, Maribor Uprising’s audience are presumed movement participants. The questioning of the role of the filmmaker remains tantamount, now including the audience as co-authors of the film experience.

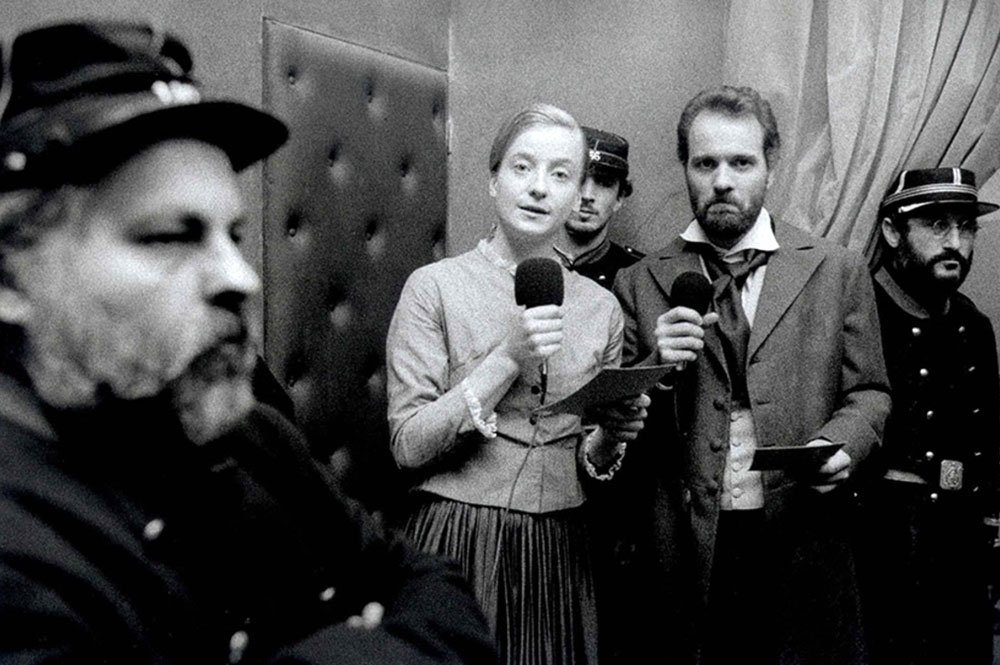

No film collapses and captures these tensions as beautifully as La Commune, Paris 1871, (2000) recognized by far too few for the absolute masterpiece it is — no doubt due to its prohibitive 5-hour length. In the film, a diverse group of Parisians — director Peter Watkins advertised and hired his actors through public audition calls in a range of different daily newspapers, in order to get people of varying political leanings and class positions — live together on a sound stage for two weeks to reenact 1871’s workers’ commune. The narrative was filmed chronologically and the dialogue was almost entirely improvised, creating a kind of reliving of the key events of the commune. Long documentary sequences of actors’ assemblies, in which they discuss the filming process, debate what the commune meant and how it relates to their lives in modern day France, give the events a living active meaning well beyond what could be achieved through simple reproduction.

All of these films ask the audience to question the authority of even the film itself. But unlike many cinematic self-reflexive gestures, they do not do so through aesthetic technique, allusion or irony, but rather through engaging people on the screen directly in dialogue. Not so much breaking the fourth wall, anarchist film often doesn’t really let it build up in the first place.

This means anarchist films are often somewhat open ended politically — they often make a point to show disagreement, dissensus or failure, demonstrating the limits of any activist’s or filmmaker’s capacity to master events — while being formally didactic. Abigail Child’s essay film Acts & Intermissions: Emma Goldman in America uses passages from anarchist thinker and activist Emma Goldman’s autobiography to draw out the relevance of the turn-of-the-century labor movement to 21st century anarchists. A little more conceptual and formalist than the others in the series, Acts and Intermissions mixes reenactment, archival footage, original documentary and abstract montage to counterpoint modern labor conditions, movements and workplaces to the thought and experiences of Goldman, revealing how much and how little has changed in the last century.

Ken Loach’s 1995 Land and Freedom is a bit of an odd man out aesthetically. A rather straightforward historical war drama about the international militias fighting in the Spanish Civil War, it does portray debates between peasants, soldiers and ideologues as they argue about the best way forward for the struggle. Along with a framing narrative about the protagonists’ granddaughter becoming politically inspired by learning about his role in the Spanish Civil War, it undermines period pieces’ tendency to treat history as a complete and knowable object, made up of great men and grand gestures.

Anarchist film, in this series at least, involves depicting, recording and remembering struggle as a living inspiration, drawing connections across time, borders and cultures as a mode of historical critique and activist memory. It destabilizes the role of the filmmaker, inviting the audience into a work of reflection, co-creation, and questioning that necessarily goes beyond the walls of the cinema. It depicts people in the process of making films and making political change, demystifying organizing, struggle, and filmmaking at once.

What is anarchist film then? Perhaps any film that shows us that anything can be changed, any authority challenged or overthrown, and furthermore that there is not one proper way to do things, that we can simply begin by acting wherever we are. Anarchist film carries struggles beyond the boundaries of their own context and movement, transports participants past their own lives and time, catches and reproduces a little ripple in the social crust that threatens to spread, expanding into a seismic event of upending and transformation.