During Japan’s 1980s bubble economy, demand for anime grew so high that OVAs (original video animation) were released directly to fans, who paid the equivalent of $80 a tape for new material. It was a unique moment of loose purse strings and unprecedented creative freedom in the medium, but even among the resulting experimentations, Angel’s Egg (1985) remains singularly esoteric.

Mamoru Oshii (Ghost in the Shell, Patlabor, Urusei Yatsura 2), and Yoshitaka Amano (Vampire Hunter D, Sandman: The Dream Hunters) pooled their talents to create a languid, abyssal meditation on belief and doubt. Slowly unspooling in long takes with sparse dialogue, its brief runtime belies its weight.

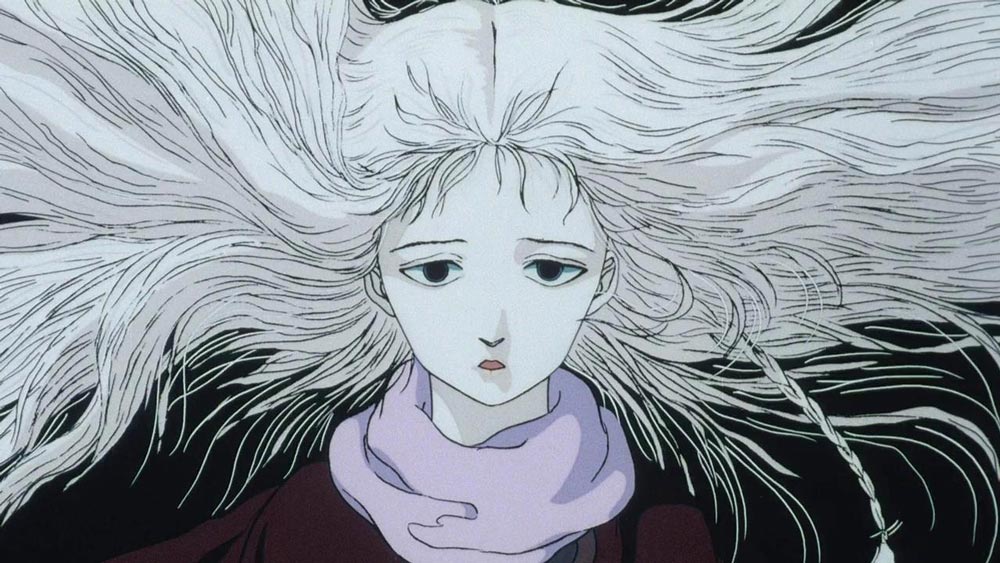

For such an intensely allegorical film, description is fairly useless, especially as the story is told through silences and empty space as much as visuals. A man watches a mechanical sun-church descend into the ocean; a perpetual twilight settles. A pale young girl leaves her observatory shelter, carefully guarding a large egg. Amid decaying baroque architecture crusted with Lovecraftian amphibians, the two meet. The man, possibly a soldier, wonders about the egg’s contents. She believes the egg contains something precious; he points out the egg will have to break for them to find out. They become uneasy companions wandering the shadowy city.

In a rare burst of dialogue the man tells a story of Noah’s dove that never returned to the ark. The uncertainty of the bird’s fate haunts him, and seems to haunt the city, cast over with a stagnant pall. The man’s curiosity and the girl’s conviction about the egg increase, as both ask and seek their answer to a repeated question: ‘Who are you?’ Do they wander a drowned world abandoned by a God still mad at his creation? Is this a limbo for those who can earn salvation at a cost?

Oshii claims not to know what Angel’s Egg is about; rumor has it the film reflects a rough period in his life. As a man who once contemplated seminary school, he was grappling with recently lost faith; after a difficult separation, he was barred from seeing his daughter. Amano’s artwork, normally flattened and simplified for animation ease, appears in full floridity, his hand visible in watercolor and ink blotches. When critics describe the film as a personal work, most mean it is personal to Oshii, but Amano’s emotional investment shouldn’t be understated. Oshii originally intended Angel’s Egg to be more comedic until he saw Amano’s designs and realized he needed to honor their full gothic fantasy.

Oshii recycled elements for the film from his never-realized Lupin III movie, also planned as a collaboration with Amano. The film was nixed by producers who thought his nuclear-annihilation ending (a hint of non-commercial instincts to come with Angel’s Egg) might be bad for the brand. In the unrealized film, a depressed Lupin decides the only thing left worth stealing is the impossible—a fossilized angel’s egg kept in a giant tower, where a mysterious young girl lives. Oshii shifted the story’s focus from a protagonist seeking meaning to two protagonists at peace with their respective ideologies, though the tension between the girl’s intentionally static, regressive faith and the soldier’s questioning makes them doomed to clash.

Unfortunately (though unsurprisingly), Angel’s Egg didn’t sell well. The film’s cold reception turned Oshii into a capitalist realist—during a recent TIFF interview he said he now develops his stories knowing future jobs depend on the current project’s success. He added, unprompted, that Angel’s Egg cost him three years without work.

In our era of “explainer” videos, it’s comforting that this movie with mystery as its focus paints a blunt demand for answers to be as fruitless as spears hurled at shadow-fish. They’re thrown by the city’s other inhabitants, otherwise ossified men coming to life in raging desperation to pin down an intangible. In their blind pursuit they miss the futility and physical destruction of their actions.

It’s easier to accept the film as depiction of one man’s personal hell illustrated by another if the concept is closer to the Jewish Sheol; not a place of post-mortem punishment, but the palpable absence of God’s light. Then again, a cavernous darkness where all share in isolated perception could just as easily refer to filmgoing. Never intended for theatrical release, it should be fittingly singular to sink down into Angel’s Egg with an audience at Japan Society.

Angel’s Egg screens tonight, October 14, at Japan Society