This essay ran in our daily email dispatch Stream Slate. Sign up here.

Last Friday, between canned food supply runs and last-minute pre-quarantine housekeeping, I made the uncharacteristic purchase of a Nintendo Switch — the last in the store, and my first video game console buy in well over a decade. Like the chorus of Twitter accounts imploring Nintendo to unleash its game early in light of COVID-19, I too have been in dogged anticipation for today’s release of Animal Crossing: New Horizons, the latest installment in the enduring social simulation series.

The Animal Crossing franchise has been lauded for its soothing simplicity, an open-world environment where players can fish, garden, catch bugs, practice home decor, design clothes, and interact with anthropomorphic villagers. First introduced in Japan in 2001 and stateside in 2003, the game came about almost as a fluke: initially pitched by creator Katsuya Eguchi as a Diablo-style dungeon-crawler for the 64DD, a failed disc drive addendum to the Nintendo 64, it had to be scaled down considerably when the system was scrapped. The dungeons were done away with, leaving a souped-up JRPG village, an emulation of the feeling of moving to a new town replete with all the fun of adult life, like small talk and paying off debt.

The series’s primary innovation is tying its gameplay to an internal clock. The sun rises in the morning and sets in the evening, seasons turn, and certain events like blossom festivals and Halloween take place only once a year, all in real time. If players neglect to check in regularly, their village becomes overgrown with weeds, and neighbors will move. It’s a temporal limitation that Euguchi meant to encourage patience, favoring small daily maintenance over long hours of binge-playing. In the United States, it was nevertheless marketed in a series of The Real World-inspired TV spots with the anxiety-inducing tagline, “the life game that’s happening every minute of every day — whether you’re playing or not.”

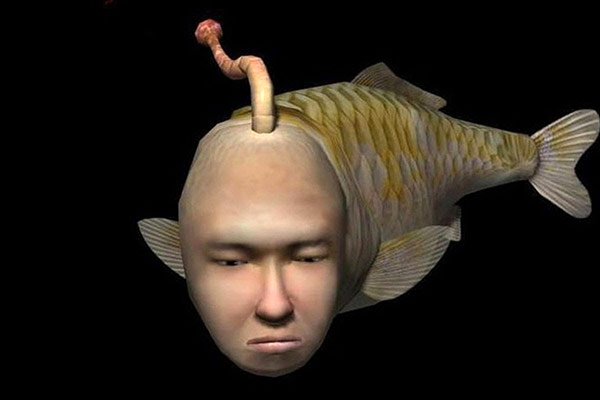

Seaman (1999)

Animal Crossing was part of a proliferation of life simulation games timed around the turn of the millenium, beginning with the much-maligned pocket fad gadget Tamagotchi and cemented by the wildly popular The Sims (2000). During this epoch of gaming, before most consoles (or many PCs for that matter) were properly equipped for online play, there was something like an arms race to produce seamless artificial life products, terrariums inside the angular black boxes of consumer tech. Some odd goods came out of this wave: the Dreamcast’s bizarro Seaman (1999) was a digital fish-human chimera — voiced in Japan by Eros + Massacre star Toshiyuki Hosokawa and in the United States by Leonard Nimoy — that players could control and talk to via voice command microphone; Black & White (2001) positioned the player as a god tasked with training tribes of AI avatars using pattern recognition.

One central predecessor of life sim gaming was Activision’s curio Little Computer Person (1985), released on Commodore 64, Apple II, Amgia, and other systems, the brainchild of artist and technologist Rich Gold. An ex-pat of the San Francisco experimental music nexus, Gold had been key in developing the user interface for Serge Tcherepnin’s People’s Synthesizer before studying under Robert Ashley and David Behrman at Mills College. He co-founded and was a roving member of The League of Automatic Music Composers, pioneers of dense “networked” electronic music and among the first to expand computer composition from solo to group endeavor. He was also known for a series of mid-’70s durational performances he called Books in a Day: he would inhabit a gallery space for 24 hours and write an entire novel, pinning the pages to the wall on butcher paper. In later iterations, he would develop AI systems to aid in the writing process.

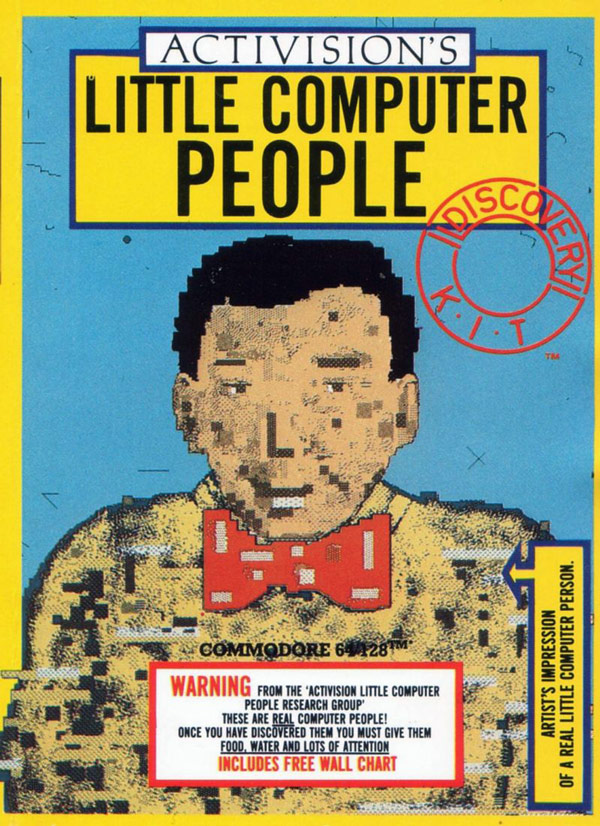

Box art of Little Computer People (1985)

Rich Gold spent much of 1980 as a visiting curator at the University of Buffalo’s Media Study Center, organizing exhibitions of the likes of Gary Hill and Bill Viola, before leaving art and academia for a career in the burgeoning video game industry as a sound department manager in SEGA’s coin-op division. There he began to devise Little Computer Person as a virtual update of the 1970s novelty toy, the “pet rock.” Its conceit was that it merely made visible for the player the tiny inhabitants that live inside every personal computer. Each copy of the game renders a digital dollhouse, randomly generating an inhabitant with a unique name and look as its occupant. In initial designs, players were only able to observe the little autonomous being, who spends his days wandering the house, playing with his dog, and listening to records. With the input of Activision co-founder David Crane, a rudimentary keyboard command system was introduced, as was the ability to play poker with your person.

Little Computer Person’s novel maneuver was positing the computer game world as one that runs with or without your input, wrapping the relatively simple algorithms that govern the game in a twee mystique, teasing out players’ instincts to nurture. It enjoyed a short-lived but robust prominence. In Japan, the game was licensed by Square, the developer of Final Fantasy, who localized the game by gender-swapping the house’s inhabitant and redubbing the game Apple Town Story; a decade later, Will Wright tapped Gold for core feedback on The Sims. Rich Gold later moved on to work as a toy developer at Mattel1 for the remainder of the '80s, leaving in 1990 to join the Xerox PARC research team under Mark Weiser. In later years, Gold became part of a fleet of computer scientists who built out frameworks for terminologies like “ubiquitous computing” and “calm technology,” devising the conceptual underpinnings of our hyper-networked era of smart tablets and the Internet of Things.

Still from Animal Crossing (2003), Little Computer People (1985)

I am usually inclined to resist video games, simulations of most sorts, technology’s attempts to ingratiate or endear itself to me, the hyper-surveillance capabilities of ambient intelligence, and the relentless 24/7 attention required of digital life — but at the moment, the immersion and assurance of Animal Crossing and the whole project of life sims seems particularly comforting. It’s partly a nostalgia trip; partly that I want to feel like I’m caring for something in my petless, mostly plantless apartment; partly I’ll be glad to have a daily time-keeping ritual; partly could be fun to have a different way to spend virtual time with my friends. (My friend code is SW-5357-0927-2787, and you’re welcome to visit.) [Ed note: my friend code is SW-3460-7463-2528.] But it’s in large part that I’d like to indulge in the fiction that there’s something friendly and reliable just behind the screens that I’ll be sharing the coming weeks with, and that the image keeps on going even if I turn it off, something that cinema, for all its good qualities, cannot totally deliver at the moment.

1 Rich Gold’s hand can be seen in the notorious feature-length product placement The Wizard (1989). He was a team-leader in the development of the PowerGlove, a largely failed video game accessory modelled after the VR prototype the DataGlove, developed under Jaron Lanier—another alum of experimental music who, per his book Dawn of the New Everything, would fight Charlemagne Palestine for the piano bench at SoHo’s the Ear Inn.