This Sunday school graduate spends an undue amount of time thinking about Pier Paolo Pasolini’s 1962 stay at the Franciscan monastery in Assisi. His residency, at the invitation of a newly liberal Vatican, fell shortly after the completion of his short film La ricotta, starring Orson Welles, which placed him in the crosshairs of anti-blasphemy culture warriors. Yet during the residency the openly gay atheist devoured the New Testament, finding in its passages a romantic sympathy for the destitute and working classes that he vibed with quite deeply—anti-capitalist messages that had once spoken, and potentially could speak again, to the Mediterranean poor. This reading resulted in his film The Gospel of St. Matthew (1964), and plans to further adapt the letters of Paul the Apostle, a project he never would realize.

Pasolini is not mentioned in Jim Finn’s The Apocalyptic is the Mother of All Christian Theology (2023)—a soon-to-be Christmas classic—but their missions as filmmakers are similar: to scrape away hundreds of years of Western doctrine and uncover the real and raw Paul: a Semitic mystic and proto-Marxist who believed, above all else, in the liberation of the slaves, workers, and betrothed women across the Roman Empire. Finn is a polemical multimedia collagist with a democratic approach to archival material. His previous films have remixed everything from North Korean Juche propaganda, the stories of imprisoned Peruvian Maoists, and Soviet intergalactic aspirations, reconstructing them into narratives that gesture toward utopia.

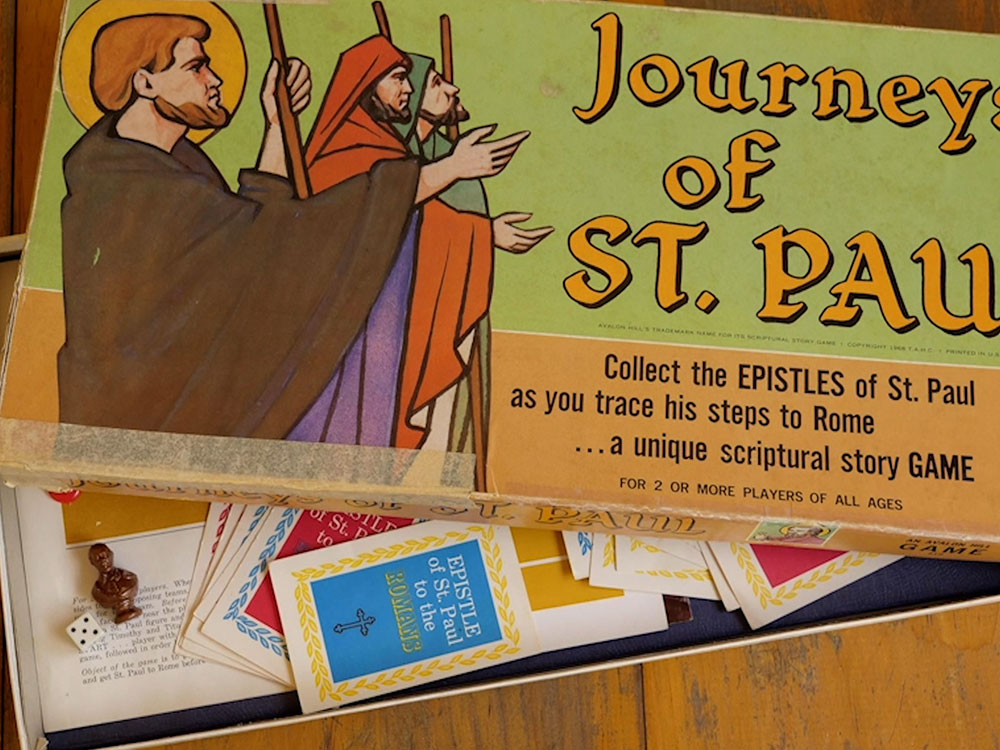

At the beginning of The Apocalyptic, Finn renders a sort of EA Sports character creation screen, envisioning different 3-D models of Paul from centuries of competing physical descriptors (after toggling through several options, the avatar settles on the most logical: “an Iraqi man”). He then combines an ungodly amount of found material to guide the viewer through Paul’s legendary missionary voyages, beginning with his sighting of the risen Jesus at Damascus and then tracing his improbable journeys back and forth across the Mediterranean. Paul’s movements are charted through actual Christian role-playing board games based upon Paul’s life (one of which involves dragons and a cassette tape imploring the player to take this game more seriously than they would a simple round of D&D); rather traumatizing tract-like animated films; and fuzzy, decomposed video and 16mm elements from old Christian film productions. Finn leaves in the faded pink acetate colors of his source material and the woozy reverberations of a rickety, shrunken soundtrack bouncing around the sound head of a Steenbeck. He also runs much of this material through a video synthesizer, reducing the image to strobing RGB colors and pulsing geometric shapes. The end result is something like contemplating an alien artifact while stricken with a bad fever. For a tale set in the Middle East, this portrayal—sketched in straight-to-video cartoons, Christian merchandise, and televangelist broadcasts—feels uniquely American; it is perhaps Finn’s most American film.

Throughout Paul’s quest, Finn continually searches for moments that have been willfully mistranslated for the benefit of modern fire-and-brimstone dogmatism. The film supports the portrayal of a democratic Paul who eschewed all differences between Jews and Gentiles; supported outcasts and weirdos, women, gender-eccentrics, and the enslaved. Paul was ultimately declared an enemy of the Roman empire, leading to his canonizing decapitation (and yes, his famously bouncing and milk-spewing felled head is depicted in Finn’s gloriously goofy-scuzzy video-game engine). Paul’s screeds against sexual deviancy, Finn argues, were in fact aimed at the upper class, who abused their slaves, children, and wives while hypocritically preaching celibacy.

The title is a quote from the German theologian Ernst Käsemann, who studied Christian complicity in the Holocaust and whose daughter, Elisabeth, was abducted and murdered by the fascist regime in Argentina in the late 1970s. Käsemann’s writings on Paul, adapted by Finn in voiceover, can be seen as a warning against self-servitude in the face of judgment. Pasolini would agree—his unproduced screenplay on Paul’s life sees the apostle transported to the 1960s, preaching to political and racial outcasts, and eventually assassinated in a scene mirroring the killing of Martin Luther King, Jr. Of course, Pasolini would soon suffer a similar fate. But perhaps, as Paul would certainly posit, if “the end” lies on the path of virtuousness, it should not be feared but embraced. Only cowards are doomers, after all.

The Apocalyptic Is the Mother of All Christian Theology screens December 6–12 at Anthology Film Archives, its U.S. theatrical premiere. The run is accompanied by a series, “Jesus Christ! At the Movies,” programmed by director Jim Finn.