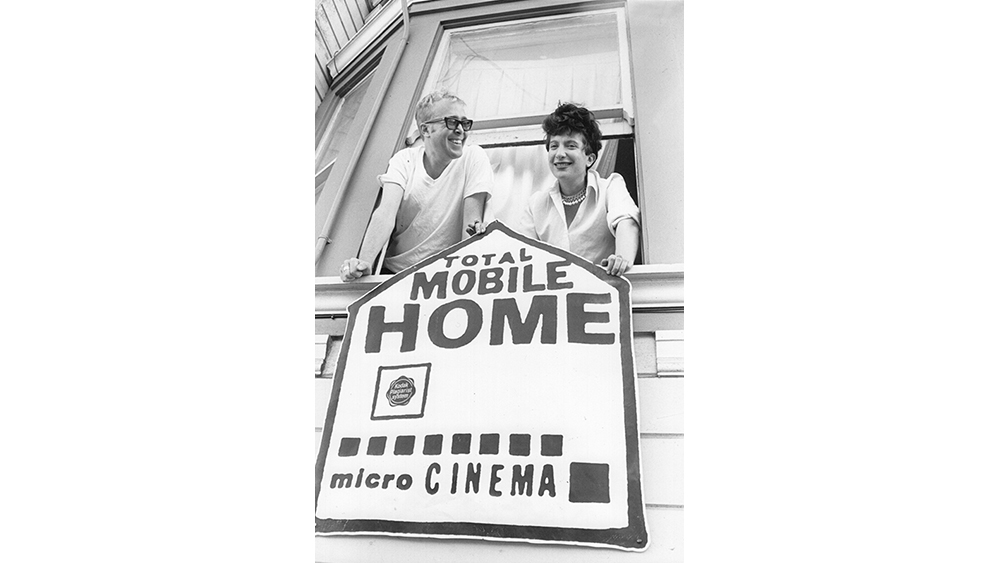

In 1994, filmmakers Rebecca Barten and David Sherman began illegally operating Total Mobile Home microCinema out of the basement of their rented apartment on McCoppin Street (near the corner of Market and Valencia) in San Francisco. Doing so, they accidentally coined the term “microcinema” and set into motion a new model for what a cinema could be—a small gathering space rather than a large receptacle for spectacles.

Total Mobile Home microCINEMA ran for about four years, hosting a who’s who of experimental cinema’s finest—Bruce Baillie, George Kuchar, Nathaniel Dorsky, and Vivienne Dick, just to name a few. These intimate screenings, which often revolved around 70 minutes or so of projected film, usually ended up running for hours on end, driven by winding conversations among attendees before and after each screening. The humble dimensions of Barten and Sherman’s microcinema were part and parcel of its homeyness—prototypical of the ethos subsequent microcinemas, whether they knew it or not, ended up adopting in the years to come. As such, Total Mobile Home microCINEMA has earned a quasi-mythic status in American independent film history—its genius lies in its unorthodoxy, which posits that the grandeur of cinema not only survives a move from the big-screen to the small-screen, but that its power becomes amplified due to an audience’s concentration, in numbers and spirit, at such an intimate scale.

On the occasion of Barten and Sherman’s guest appearance at Light Industry tonight, where they will present a new live cine-essay looking back at the life and times of Total Mobile Home microCINEMA, I spoke to the duo about the history of the storied microcinema, its Arizona afterlives, and how San Francisco has changed since the ‘90s.

Nicolas Pedrero-Setzer: In your description for the upcoming event at Light Industry, you describe yourselves as “accidental neologists” with regards to the term “microcinema.” What does the term “microcinema” mean to you?

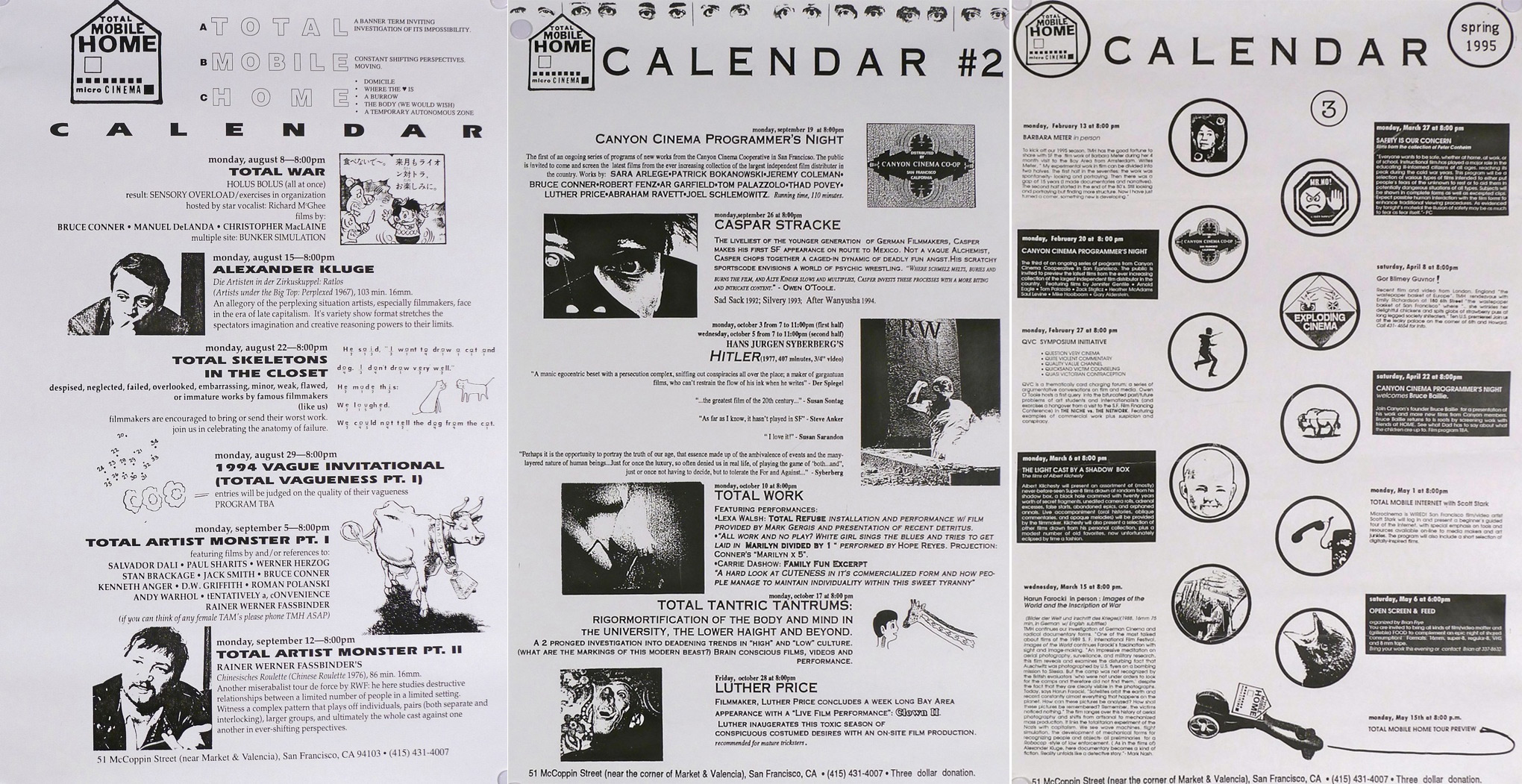

Rebecca Barten: We remember quite clearly when we thought of the name microCINEMA. It was a conversation at our kitchen table. micoCINEMA was not just microCINEMA, it was Total Mobile Home microCINEMA. Linked up, it was part of an investigation into all of these terms together. We realized it was not going to be a neat endeavor early on, so we broke it up. I’ll read it to you. We defined “Total” as a “banner term inviting an investigation of its impossibility.” “Mobile,” we defined as “constantly shifting perspectives and moving.” “Home,” we defined as “a domicile where the heart is, a burrow, the body we would wish, and a temporary autonomous zone.” And “microCINEMA” we defined as “a word of our own invention, a small space for the projection of film and a category of action.”

David Sherman: For us, all of these words were conceptual investigations. There’s been nobody who's ever written about us and referred to this definition, as well as the conceptual nature behind the project. Even the word “microcinema,” for us, was a contradiction. “Cinema” tends to connote a large space—big image, large audience. Adding “micro” in front of it creates tension. They don't work together, but now nobody thinks about the contradiction between those two terms. They just seem to fit well together, though that wasn't our initial intention. It was more about the dialectic.

NP: I'm curious about the fact that all of the terms you've described have an action component to them—in the “autonomous zone” or in the “projection of film.” Alongside the conceptual approach, there’s also a political dimension to the creation of a microcinema, the term “microcinema,” and your own microCinema. What was the scene at the time, both politically and artistically, that influenced the making of your space?

RB: All through my twenties, for eight years, I lived in Baltimore. It was about 1983 and I was at the film department of the University of Maryland, which was founded by the filmmaker Stan VanDerBeek. When I showed up there, to poke around and see whether it was a department I was interested in engaging, it turned out that he had just died. The film department was a wreck, meaning there was a nice amount of film equipment for both people interested in making Super 8 and 16mm films.

Right from the get go, I heard that there was a room full of all of the bits and pieces of what Stan VanDerBeek had left behind on film. His family had come and taken his complete projects, but he had left behind lockers and lockers of found footage, and bits and pieces of elements from different experiments. Having not ever even touched film before, the very first thing I did when I got there was to get the student job of going through all of these film elements on rewinds and teaching myself how to come up with a system of viewing, logging, and becoming intimate with film.

I started to closely identify myself with an experimental film practice by making my own films on 8mm and 16mm, and then becoming active as a student who got little grants to invite people who I had become interested in, such as Cecile Starr, with her Len Lye book [Discovering the Movies: An Illustrated Introduction to the Motion Picture, 1972], and Barbara Hammer, among others. Within the next couple of years, I became involved in a short-lived and small anarchist film collective where we started borrowing films from the Enoch Pratt library collection and showing our own films, as well as other people's films. Also, unbeknownst to me, I was talking to David Sherman on the phone because he was already working at Canyon Cinema. One of my greatest pleasures was to pour over the Canyon Cinema film catalog and talk to David Sherman on the phone. I met him when I moved from Baltimore to San Francisco, and within the first month or two, I was hired by Steve Anker and Ernie Gehr to be the office assistant of the film department at the San Francisco Art Institute. That’s where I met David, who was beginning his graduate program at the San Francisco Art Institute.

DS: I went to Hampshire College, which was an experimental college that had a very prominent film program. The Canyon catalog was in the film office and I would look through it. The catalog had a mythic quality to it, because at the time The Film-Maker’s Cooperative’s catalog in New York City didn't have any photographs. It was all text. But Canyon did have photographs and it was graphically much more interesting. That was something that was very enticing to me, so after college I moved to San Francisco and started interning, and then working, at Canyon Cinema.

I was there for 12 years, I believe. There was a huge amount of education that happened there through viewing films in the collection, conversing with filmmakers who would call in about various issues, and seeing how the distribution system worked with various alternative venues versus colleges and institutions that rented films. At that time, a lot of these first generation, New American Cinema filmmakers were still alive. People like Bruce Baillie, Peter Hutton, and Kenneth Anger would come through. And, I would talk on the phone with Stan Brakhage and so forth. That gave me a sense of the work’s connection, nationally and internationally, as well as specific films and the aesthetic investigations that were represented in the collection.

NP: Once you two met, how long did it take until you founded the microcinema?

RB: I moved to San Francisco in the beginning of 1993 and we began Total Mobile Home in 1994.

DS: We had an overlap of one year during which I was in graduate school. At least for me, there was a disappointment with the dialogue that happened in this graduate program. It seemed like there could be alternatives to discussion and viewing experiences outside of the graduate program. At that time in San Francisco, there was a big scene and there were a lot of screenings going on in the city. The San Francisco Cinematheque ran three shows a week, Craig Baldwin’s Other Cinema was every other Saturday, the Pacific Film Archive had a night of experimental film every week and a night of video-art every week, the Exploratorium had experimental film screenings, and there were films shown in other contexts as well. But somehow, in the place between the institutional presentation of a visiting artist and the slightly more, or way more, chaotic environment that Craig Baldwin was screening films in, we felt that if there was such a vital scene, then maybe there was an opportunity to do something that combined a concern for intelligent engagement that wasn’t academic and institutionalized, while also being open to experimentation, new ways of presenting work, and developing community that was different from anything that was happening at the time.

RB: David and I realized, soon upon meeting, that we were both completists in the sense of wanting to go to every program that was available. Often, the kinds of conversations that we were having with each other, or with friends after each screening, seemed to be of our own making. When we made our space we designed it in such a way that… And this is another interesting thing, when we interviewed people recently in what we called an oral history project, we were curious about what people remembered about the physical space. A lot of the memories are personal memories, emotional memories, political memories, but remembering the facility itself really varied from person-to-person. Some people said, “Oh, there were 50 seats and a very, very low ceiling, and a projector in the space itself.” Which, there never was. We had actually sawed a hole in the utility room so we could have a proper projection booth and not have the sound of the projector in the space.

We really wanted the architecture of the space, with what was available to us illegally since our landlord never knew that we had made a space out of his basement, to be an architecture that allowed for conversation. That conversation would happen before the show in a space that we called the Grotto, which was just the utility room. Then, there was the space itself. And then, there was a backyard. Often, these evenings that were, say, 70 minutes of projected image, would end up being three hours in all, or more, because of all of the conversation and dialogue spilling out of the event itself.

DS: The design issue was somewhat out of our control, in the sense that Rebecca had found a place on the first floor of a San Francisco apartment building. The basement space was directly below—the hallway and the utility room. We realized that this space wasn't being used for anything—it was just storing bicycles and had all sorts of detritus that was dirty and funky. There was something to whether this space, which was completely unused and small by most people’s sense of a cinema space, could manifest as a unique space for a viewing experience and community engagement. Then, as far as the proximity to the sound and stuff, we didn't have to worry because Rebecca's apartment was right above. To use the bathroom, one would have to literally go up the stairs, through our kitchen, into the bathroom and…

RB: Not flush the toilet because the plumbing ran right over the space. We really did embrace the notion of the microcinema being part of the home. For example, for our very first show we had a live video-feed from the bedroom itself down to the cinema. When we did a show at the San Francisco Cinematheque, we called it “From the Bedroom to the Banquet,” and we took our little home logo and taped it up over the Cinematheque sign.

DS: We handmade wooden benches that two people could sit on and the space looked a bit monastic. We couldn’t afford to buy chairs, but the aesthetic worked. People responded to it; for example, Harun Farocki came with Kaja Silverman and he said, “This looks like a bunker.” Then we did a show with Nathaniel Dorsky and he referred to the space as a chapel.

RB: That reminded me of Stan Brakhage’s practice of going to movie theaters and referring to them as “The Temple of Light.” Whatever was screening, it was always “The Temple of Light.”

DS: We were also listed in alternative weeklies, as well as the daily paper. Even though we had no permits or anything like that, there was a way of getting out what we were doing beyond flyers and calendars. We made physical calendars and wrote program notes for everything, as well zines for different shows. The context of how we were presenting what we were presenting was incredibly important. That leaned more toward the institutional side of things, but it was done in a completely DIY-manner.

NP: With people coming in all the time and being listed in different alt-weeklies, how long did it take for your landlord to notice?

RB: He never did.

DS: He lived in Hawai’i.

NP: Regarding the first program, how did it come to be? What was it and how did you organize it?

DS: Part of it was just about the celebration that we had put up drywall, installed a sound system and lights, built the benches, and all of that. Since we were already part of the local film community, there was some anticipation about this new microcinema. The first program was really focused on defining the new space with its concepts and having different works like the video-feed to create a collage around the concept. That tended to be an operating principle for a lot of our shows. It wasn't just what people wanted to see or how we could get the largest audience, because the literal constraint of smallness created such a different dynamic from any other space. We embraced that and it gave us a different way of looking at what could be done, and what connections could be made.

The intimacy and the connections between the garden and the grotto made it so that the space was both informal and structured. That intimacy allowed for very engaged conversation and community. That’s one of the things people responded to when we asked them to describe the physical layout of the space. They started talking about the connections and the conversation in the community, as well as the freedom of expression, which had nothing to do with the wooden benches. The size of the place informed the audience's consciousness.

NP: This microcinema model is also something you've taken elsewhere. At one point you left San Francisco and started other cinemas.

RB: One of the two other major projects we did was the Bisbee Underground Film Festival in Bisbee, Arizona. It’s a town that’s a couple of miles away from the border with Mexico, a small mining community that has a population of a couple thousand people—these are people who have moved there from various cities.

DS: It’s an artist community. There was a WPA Park outside with an amphitheater, so we did an experimental film festival there for three years in a row. We invited George Kuchar one year and had other visiting guests. People would bring their lawn chairs and watch.

I remember there was a Scott Stark film that we showed where somebody was so disturbed by the flickering images that they threw up. One of the things that was interesting was that a lot of people had migrated from New York. For instance, the filmmaker Dick Preston had been there since the ‘70s and he was friends with Jack Smith, and Jack Smith shot Flaming Creatures [1963] on the roof of this theater that was right next to Dick Preston's apartment. So, he gave us a print of Un Chien Andalou [1929]. There were a lot of artist expats and local townspeople who were really into the festival.

RB: Over a period of three days, for the three years that we did the festival, we would have 800 people dragging their lawn chairs—the town is built up-and-down mountain sides—down to an outdoor WPA Park and watching whatever we projected to them for free. We were showing a lot of experimental films, but we were also doing things like live music accompaniments. We would find an old William S. Hart silent western and an Arizona-based pianist, and then drag a piano to the park to do a live score for a western. But, we were still using our Total Mobile Home approach toward collaging the evening. After that, our third collaboration was another microcinema that we called Exploded View.

NP: Where was this?

DS: We found a storefront in downtown Tucson, in the arts district, that was very reasonable, so we built out a gallery space that was significantly bigger than the basement space of Total Mobile Home. We would do visual art shows and things like that. It was a bigger space, so we did things like poetry readings—a lot of things grew through collaborations with the community. It was a really wonderful space that we've consequently turned over to another group of people to operate and program.

The community was very different from the San Francisco community in the ‘90s. There was less of a history of media art. The space was significantly bigger, which meant people were less intimate with one another. The same kinds of connections weren’t happening there—that could be historically related or spatially related. We did that for eight years, but it was very different because the audience was less attuned or interested in experimental film.

RB: There were maybe a handful of people who shared historical references with us. We may have actually called it “Total Mobile Home,” except that the term “Total Mobile Home” in the southwest refers to “mobile homes.” Occasionally, we still get correspondence from people thinking that we actually sell mobile homes, or that we ran our original space out of a mobile home. So, we called it Exploded View instead.

It was an entirely different project. We ended up functioning more as a destination. I mean, our audience was quite open and excited about what we were going to bring to them, but really didn't have the references. That was exciting for us because it was all so new to the people in Tucson. We ended up doing a lot of collaborations with local musicians, which is probably one of the most robust parts of the artist community there. For example, we've been carrying three copies of Un Chien Andalou for years and we ended up proposing a night called “Three Dog Night,” where we had three different bands scoring the same film. We had another night called “Fall of the House of Usher Times Four,” where we had four different bands sequentially scoring music for the same film. It became quite the exciting thing for local musicians to explore film accompaniments. But then, in addition to that, we became part of a corridor of cinemas in that part of the country where people would propose a stop if they were touring through there.

NP: Now, with this new live cine-essay you’re presenting at Light Industry, it seems like you’re going on tour. What other cinemas are stopping at?

RB: Just one on this trip, Pittsburgh’s Sound and Image.

DS: But we are looking for microcinemas. We want to do a western New York tour that includes the Visual Studies Workshop [in Rochester] and Squeaky Wheel in Buffalo. Scott MacDonald is interested in hosting us at Hamilton College, and we’d like to do a show in L.A. Perhaps we also go to Great Britain and other parts of Europe in a year from now. We are doing Experiments in Cinema in Albuquerque later in May.

RB: Maybe the Brattle in Boston…

DS: I mean, we just don’t know how it’s going to translate for much larger spaces, but we’re willing to give it a go.

NP: What is it that prompted this desire to look back at the history of Total Mobile Home microCINEMA?

RB: For me it was coming back to San Francisco on the occasion of Craig Baldwin’s Avant to Live! [2023] book release, which also happened to be timed with Scott Stark’s 70th birthday celebration. We really had a moment around the release of Craig's book when we were able to assess the partial collapse of the San Francisco economy. Microcinemas have always depended upon available cheap space, so the fragility of everything really hit us like a locomotive, even though it's been practically 30 years since we first started the Total Mobile Home project. That history is still very fresh and alive with the community that still exists here.

We’ve always maintained our archive fairly well. To call it an archive would be a bit pretentious since what we've carefully taken care of amounts to a stack of boxes of film and video-documentation of shows that we did, all of our calendars, all of our program notes, our correspondence, and our documentation for other projects. We decided that it was time to revisit all of this material and make it into a program for everyone’s sake, and to put ourselves at ease about not losing our documentation. I mean, we’re always scolding other people about how they don’t keep better track of all of their material and documentation, so we really wanted to put ourselves at ease about getting a handle on all of this stuff.

DS: Realizing how fragile the scene is and seeing our mentors retiring, or leaving the Bay Area due to its precariousness, presented us with an opportunity to revisit our work. We had 8mm and video-documentation of various shows, including Luther Price and Stuart Sherman, both of whom have passed. George Kuchar, he’s no longer with us.

RB: Carolee Schneemann.

DS: Robert Frank.

RB: Bruce Baillie.

DS: The retrospective surrounding Craig’s work and seeing the community that was still in San Francisco prompted us to look at our stuff and reinvest in our history, not just be nostalgic about what we did, but also to honor artists who were very influential to us and who we were able to work with.

NP: What’s become of the space Total Mobile Home was in?

DS: We visited it. It’s in the essay since part of the piece is about looking at aspects of San Francisco that have changed. One of the things that’s different is that people, because of the easy access to media available through streaming, don’t experience a certain amount of discomfort that sometimes audiences feel about really engaging with one other people in personal spaces…

RB: The space is now a storage room. On our last visit to San Francisco, we visited the building and rang every doorbell. A woman, perhaps the last person still living in that six-unit Victorian on McCoppin Street, popped her head over the balcony and let us into the basement so that we could visit the utility room. The cinema space itself was boarded up and she explained to us that a fire had happened.

DS: This line between makers, audiences, and audiences who are also makers, or audiences who are also artists in different respects, seems to result in slightly less exchange going on among audiences. Maybe people are just out of practice because so much communication is done through email and other abstracted forms. I don't know if what we did then could work now. Part of this program is to examine some of those constructs that we have always felt were very important, but are also more at risk due to the economy and where artists can live.

The closing of the Art Institute was a huge blow to San Francisco. So much of the infrastructure has changed. Once again, not to be nostalgic, but looking at how we were able to create this community around different concepts and presentations, might reveal a way forward for people doing microcinemas now.

Total Mobile Home microCINEMA takes place tonight, December 3, at Light Industry.