A riveting cult oddity and a minor miracle of happenstance, comprising one part documentary and two parts fictionalization, The Beaver Trilogy (2000) is a portrait in triplicate. Its primary subject is a 21-year-old wannabe entertainer from Beaver, Utah—billed here only as “Groovin’ Gary”—but the film is no less starkly revealing of its maker, Trent Harris. The Beaver Trilogy opens without ceremony or explanation on the footage of the pair’s fateful meeting in a Salt Lake City parking lot in 1979, as recorded by the director. Harris was testing a video camera outside the TV station he worked at when he spotted Gary, snapping pics of the lot like it was Monument Valley. Gary, spotting Harris in turn, moseys his way and proceeds to launch into a series of heartily unconvincing to-camera celebrity impressions. The bell-bottomed fellow is positively giddy at the prospect of “making the tube,” strewing his patter with squawks of laughter and aw-shucks asides: “Boy, I love hamming it up.”

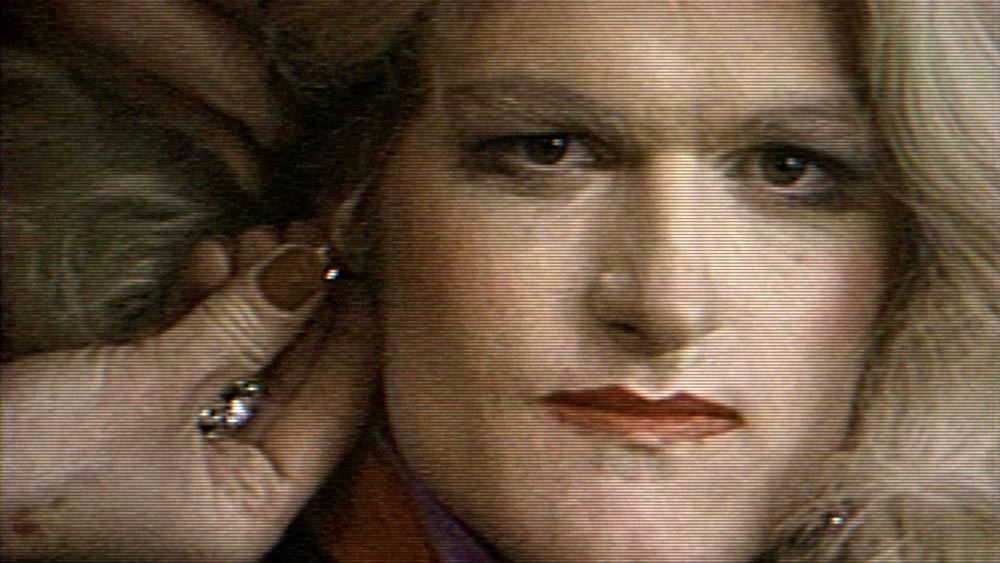

Gary’s impromptu monologue is a mini-masterwork of anti-comedy. How could Harris rebuff the young man’s exhortations to come document the talent show he was putting on, in which he was to perform, in drag, as his idol, Olivia Newton-John? From the 8 a.m. make-up call at the Beaver mortuary—note the touch of gay panic in the mortician’s opining that Gary isn’t doing one of his other, which is to say male, impressions instead—to the falsetto grand finale, the talent show makes for a queasy piece of small-town spectacle. Gary’s good-natured gusto cannot dispel the acute second-hand humiliation.

Harris’s footage never aired, for reasons that would become part of the text in the dramatized shorts to follow—in which the Beaver Kid would be reincarnated, through two more serendipitous turns, first by Sean Penn and then a few years later by that screen oddball non pareil, Crispin Glover. Harris caught both actors on the cusp of Hollywood fame, just before Fast Times at Ridgemont High (1982) and Back to the Future (1985), respectively. The Penn version is a scrappy affair shot on black-and-white home video for a reported $100 (most of which, Harris says, went toward pizza); the 16mm Glover version—Harris’s American Film Institute thesis film—put fifty grand into the sympathetic, and lightly mystical, expansion of the Kid’s backstory. Both dramatizations feature an unscrupulous director character (Ken Butler) who dismisses the Kid, now called “Larry,” when he expresses post-show anxiety about “that Olivia number,” and in both versions, Larry subsequently attempts suicide—a plot point Harris later confirmed to have been based in reality.

With that disturbing revelation, Harris’s doubling-back to the story reveals itself as a kind of repetition compulsion. The insertion of an ugly self-portrait, coupled with the successively happier endings he gives his Kids, appear as gestures of atonement. Harris began screening the three films bundled as one in 2000 and together, they function as a coming-out fantasy for Gary—not necessarily as queer (though it can certainly be read that way), but as someone who proudly, defiantly grooves to a beat all his own, long blonde wig or no.

The Beaver Trilogy screens tonight, June 11, at Nitehawk Williamsburg as part of the series “Additional Dialogue.” Trent Harris will be in attendance for a Q&A.