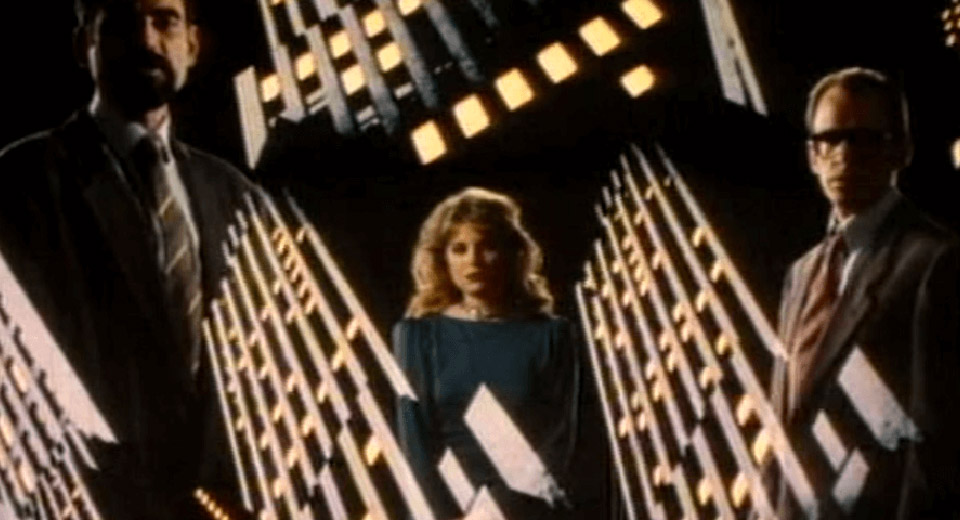

“See? This is just like a conversation,” one man observes to another as they sit at a bar in The Big Blue, Andrew Horn’s No-Wave noir from 1988. The film, which is screening as part of Spectacle’s tribute to the beloved filmmaker and artist who passed away in 2019, is full of circular, tautological exchanges, where characters consistently comment on the present moment, unable to see too far in front of their immediate surroundings. Much as his previous film, the cult-classic Doomed Love (1983), was an exaggerated riff on the Hollywood romantic musical, The Big Blue re-ups tried-and-true noir storylines populated by double-crossings and double-entendres, adding a healthy dose of Horn’s sensibility, at once stark and surreal. Their world, like their storyline, is a facsimile of something familiar — with sets consisting of two-dimensional reconstructions of Manhattan’s skyline designed by Anne Stuhler, who turns the city into a kaleidoscopic, expressionistic version of itself.

What “The Big Blue” is, exactly, isn’t entirely clear, but according to the eponymous jazz tune that plays throughout the film, it “isn’t something that you want.” With a script penned by Jim Neu, who also contributed his dispassionate dialogue to Doomed Love, The Big Blue tells the story of Jack (David Brisbin), a private detective who begins his journey confident in his role as a bystander, maintaining a safe distance from the shady dealings he’s observing from afar. Neu himself plays Howard, whose wife (Sheila McLaughlin) hires Jack out of fear he’s having an affair. Jack instead finds Howard at a bar, pretending to have a “normal” conversation with Max, his co-conspirator in a drug deal. It’s not long before he’s led into their unsavory underworld by Max’s lover Carmen (Taunie VreNon), the femme fatale at risk of becoming the ultimate victim of Max and Howard’s scheme.

"Surveillance gets to be a habit,” Jack says. “You look at something like it doesn’t include you.” The Big Blue is a film about watching, with sequences revealing themselves to have taken place on someone’s television within the larger film itself. As Jack listens to coded conversations among criminals, we realize that anything can sound like nothing, and nothing can sound like everything. Something as innocent as pillow talk between two lovers can sound suspect: “I like it when I believe you,” Carmen says. “I like it when you like it,” Max responds. Neu’s cryptic syntax mimics the spiraling soliloquies of the poet Christopher Knowles, who contributed words to Horn’s short film Cloud Dance, along with Einstein on the Beach, the 1976 opera by the director (and Horn collaborator) Robert Wilson. Here, language becomes a tool for characters to distance themselves from events as they unfold, the only device that rivals the power of the Big Blue itself. But, as the song goes, you can forget about what you want, forget about what you want to do, if you’ve got the Blue.