Woody Strode has maybe fifteen lines of dialogue in Black Jesus (1968), his first and only starring role. (Despite playing the title role in pal John Ford’s Sergeant Rutledge [1960], he was fourth-billed.) After twenty years in Hollywood, during which he turned in dozens of memorable supporting parts in westerns and jungle adventures, Strode decamped to Europe in the late 1960s in search of better roles and salaries. He found both in Black Jesus, director Valerio Zurlini’s fictionalized account of the asssassination of Congolese Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba in 1960. Strode’s nearly silent performance courageously assumes the lofty mantle of the film’s title. The film is the most formally adventurous entry in the Museum of the Moving Image’s fantastic series dedicated to the actor.

Strode’s Lumumba stand-in, Maurice Lalubi, doesn’t appear until the fifteen-minute mark, after Belgian soldiers tear through Congolese villages in search of the rebel leader. He is not seen in this chilling sequence of colonial violence, but he can be heard preparing his followers for his imminent capture. He beseeches a rapt audience to respond peacefully to the violence against their independence movement while Zurlini cuts to blunt images of corpses lying in the street. The reward offered jointly by the African puppet government and European colonizers increases rapidly until one of Lalubi’s followers betrays his location. At this moment Zurlini offers our first glimpse of Strode, a heroic tracking closeup straight out of Stagecoach (1939). The peaceful revolutionary is then thrust into a prison cell with two thieves and tortured. The sequences are more terrifying than gruesome, with Strode’s prolonged cries and anguished expressions communicating more effectively than any closeup of the nails being driven into his hands would have.

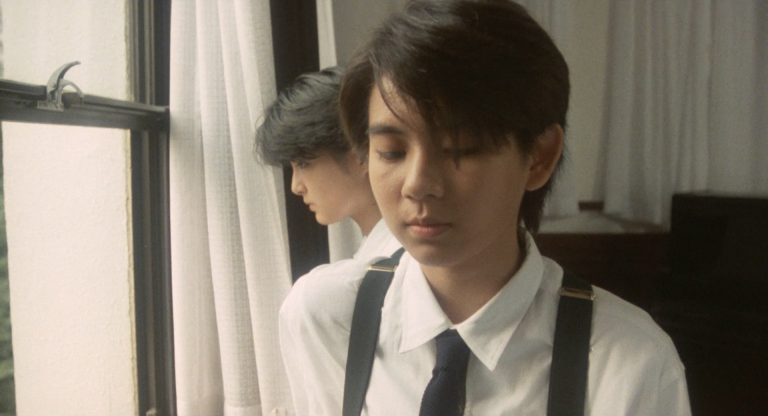

The witnesses to Lalubi’s teaching and suffering are Zurlini’s primary visual concern. Where standard film grammar might dictate one or two shots of attentive disciples absorbing the message, Zurlini piles on two or three times that many. Similarly, the soldiers, some unnerved by the process, others unmoved, observing his torture are seen in more closeups than Strode himself. Foregrounding adherents and tormentors during this messiah’s final hours has obvious biblical connotations, but the technique also functions as a provocation to consider our own relationship to colonialism and its enemies.

Black Jesus screens this afternoon, February 27, and March 4 at the Museum of the Moving Image as part of the series “The Legend of Woody Strode.”