The Yugoslav Black Wave remains one of the most fascinating and subversive golden ages of cinema history, an all-too-brief period in which the stars aligned for the country’s film industry. Emerging from the Second World War, Yugoslavia’s Socialist government, led by Tito, set about rebuilding the nation, sometimes by force, transforming a mostly rural population into an urban one. The state invested heavily into film, the fruits of which gradually emerged. By the time the Black Wave flowered, from the mid-1960s until early 1970s, it did so with a unique sense of the geographical reality of the country, concretely setting films in recognizable parts of the country rather than nowhere in particular, as if the films are saying not just “this happened”, but “this happened here.”

Yugoslavia was, after all, a country made up of six republics, comprising various ethnicities, languages, and religions; it contained dry, rocky coast; karstic mountains; untouched forests; and vast flatland. Much of the rural population—which was, prior to the Socialist era, largely illiterate—moved to rapidly expanding cities with the prospect of education and employment. Tito recognized the propagandistic, nation-building power of cinema to psychologically conjoin a fragmented people in this rebuilding project, particularly in the wake of the mass trauma of the war.

The Yugoslav film industry was federalized, with each republic gaining its own state-run studio and infrastructure, situated in Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Serbia, Montenegro, and Macedonia (the autonomous regions of Vojvodina and Kosovo would get theirs later, too). This decentralized structure allowed the then-nascent film industry to develop along multiple lines and structures, with regional and cultural specificities, although the smaller republics such as Montenegro tended to focus on documentaries.

Investment came not just from the state, but also from abroad: American and Italian productions frequently used Yugoslavia for location shoots, lured by cheap crews and geographic variety. The domestic crews, in turn, learned from master craftspeople. Investment, technical infrastructure and a reasonably lenient censorship regime made the 1960s a prime moment for Yugoslavia’s filmmakers to emerge as artists. And although the state may well have wished for a rather sunnier vision of its post-war success, the Black Wave filmmakers instead found a false utopia, forever falling short of its purported ideals and directives.

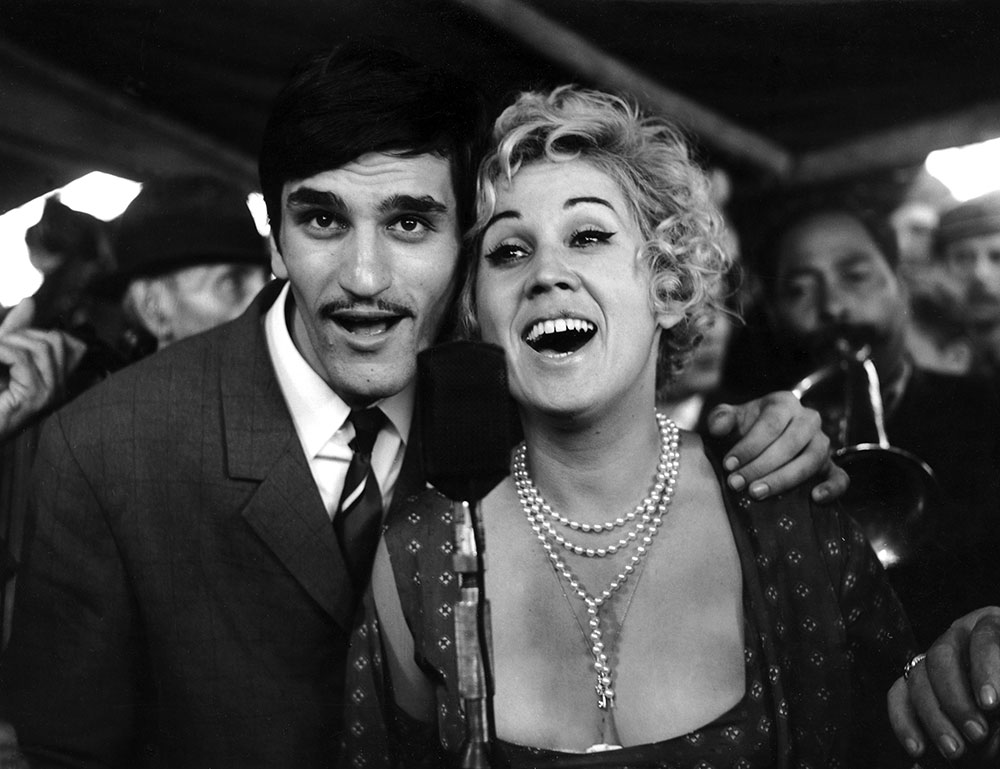

The single greatest achievement of the Black Wave—the bleakest and the blackest—may well be Živojin Pavlović’s When I’m Dead and Pale (1967). It tells the story of Jimmy Barka (Dragan Nikolić, one of the major stars of his era), a layabout from the Serbian countryside. Fresh out of a job, he starts working as a folk singer in village bars and kafanas. He’s really not very good, but he is young and good-looking, and folks seem to like him. He fucks and drinks his way through the dog-ends of provincial towns, manipulating lonely wives and naïve teens to keep a roof over his head until eventually he makes his way to Belgrade, where he auditions for a talent show. Competing against psychedelic rock ‘n’ roll bands, he comes face to face with his own redundancy, is booed off stage and returns to the sticks, tail between his legs.

Pavlović isn’t interested in Jimmy so much as the world in which he finds himself. The provinces are desperate and lonely, a landscape of dashed hopes. The village halls and kafanas in which Jimmy plays were newly built by the Socialist state, but the accompanying Socialist ideals have yet to arrive. The city is no better, a hostile place in which Jimmy’s easy charms are suddenly ineffective; the youthful trends his generation has adopted in the city are light years ahead of him, leaving him swirling in self-hatred. The rural and the urban exist on either side of a vast chasm that is not easily crossed. When I’m Dead and Pale was only Pavlović’s fourth feature, but he had already refined his neorealist style, forgoing close-ups, favoring long takes, allowing the viewer to gaze over the geographic reality of Jimmy’s world.

Previously, Pavlović had directed a segment of Grad / City (1963), an anthology film with contributions from Marko Babac and Vojislav “Kokan” Rakonjac. In “Obruc / The Hoop” a man (Stojan Arandjelović) journeys out from the city center to the suburbs over the course of an evening, with an expressionistic, noir atmosphere encroaching as time passes. The man’s journey to the edge of the city and to the edge of his memories is increasingly shrouded in darkness; he walks unlit roads as if descending into hell. It remains the only Yugoslav-era film to ever have been officially banned (other films that fell foul of censorship laws were either stopped before completion or conveniently made “unavailable” by distributors very soon after release). Grad explores the violence of modernity, following one man’s journey to what is either the edge of the abyss or a suburb of Belgrade. Though the film is devoid of any obvious critique of the state, the censors may have seen something of their own circumscribed paths reflected in it.

Grad is often regarded as a key starting point for the Black Wave, with watershed moments coming thick and fast thereafter. But the wave was contiguous with the wider Yugoslav film industry, and filmmakers had been laying the groundwork for years. Dancing in the Rain (1961), directed by Boštjan Hladnik, ostensibly tells the story of a love triangle in the Slovenian capital, Ljubljana. Beneath that is a story about coming to terms with the vast changes of post-war life: its structure and order, but also its utter shock to the soul, transforming a previously sleepy region into an industrial powerhouse (Slovenia remains one of the richest parts of the former Yugoslavia).

One of the protagonists, Maruša (Duša Počkaj), is an aging actress who, in a dream sequence, goes back to the small Alpine village of her birth, imagining herself as a star returned, her precarious living conditions and craving for fame belied in her fantasies. In an ambitious film, powered by elegant, expressionistic camerawork that flows through the city streets yet always seems stymied by their shadows and dampness, Maruša’s dream sequence is the only segment that feels fresh and vibrant. In hurtling so quickly toward modernity, the three protagonists have crashed and find themselves stuck, running through the same cycles of disillusionment and hopelessness. It’s as if the divide between the rural and the urban is too great for one generation to bridge.

If these films depict the inability of modernisation to solve ills of the human soul, then Aleksandar Petrović, perhaps the most high-profile name of the Wave in his day (though it’s his contemporary Dušan Makavejev who seems to have had the most staying power) found ways to articulate the hardships of the rural world. I Even Met Happy Gypsies (1967, whose literal Serbo-Croatian title is Feather Pickers) is set in the northern province of Vojvodina. Much of that region is entirely flat and agricultural, an endless horizon stretching off into the distance. It should feel limitless, but it is more often claustrophobic, particularly in winter, when the fog seems to stick to your lungs, and then later, when thawing snow turns the plains into a giant mud bath. The film deals frankly with the lives of Roma communities, who were often excluded and marginalized by the state, and who were mostly cast in Yugoslav films as sideshow characters: musicians and thieves. Here, yes, some exist as musicians and thieves, but they are also represented as families, friends, enemies, and lovers. Rural poverty dominates the film, though Vojvodina was then one of the richest agricultural heartlands of the country. The economic benefits of Yugoslavia’s post-war boom failed to reach its marginalized communities. The state barely exists in I Even Met Happy Gypsies, whose characters exist largely outside of the law and have to build their own means of self-management.

If that all sounds gloriously depressing, it’s because it is. The Black Wave earned its title because a critic for one of the national papers accused the movement of looking at Socialism through “dark glasses.” But it was a movement that challenged the supposed utopia of the state head on, that searched up and down the country and found its ideals wanting, regressive habits gestating, and harshness aplenty, whether in the city or in the country, high up in the hills or in the muddy plains.

“Black Wave to White Ray: Yugoslav Films of the 1960s” runs through September 21 at the Museum of Modern Art.