Shot on the streets of New York City sans permits for just $20,000, Blast of Silence (1961) follows the hitman Frank “Baby Boy” Bono (writer-director-star Allen Baron) in his repeated attempts to extirpate a well-protected target. Baron’s lo-fi aesthetic, which tightrope-walks between intimacy and grotesquerie, is steeped in the textural filth of several converging cultural moments. The unvarnished realism of its black-and-white 35mm photography rebukes the polish of a waning studio system, laying the groundwork for both the American neo-noir and the American independent film. Its coarse expressivity, sonic flights of fancy, and provocative interest in violent subjects are all symptoms of its representation and embodiment of disaffections––aesthetic, moral, institutional––that mainstream filmmaking began to properly reckon with in the late ‘60s.

The action in the film is serenaded by scintillating jazz and a second-person narrator, whose bilious responses to Frank’s surroundings––and taunting recitations of his darkest impulses––lock us into the young man’s tortured headspace. Though his background remains shady throughout, the film opens with an abstract rendition of Frank’s traumatic birth. As the camera makes a forward thrust through a pitch-black tunnel into daylight, a woman’s screams are cut short. “Your job is done,” says the narrator, and Baby Boy’s cries blend with the sounds of train-tracks and swelling strings. Born in pain, born in hatred, the film suggests Frank was bred for murder. His evident maladjustment manifests in repressive and compulsive isolation; a pillow shot of a seagull flying apart from its flock accompanies the declarative mantra: “On your own again, nothing to worry about.”

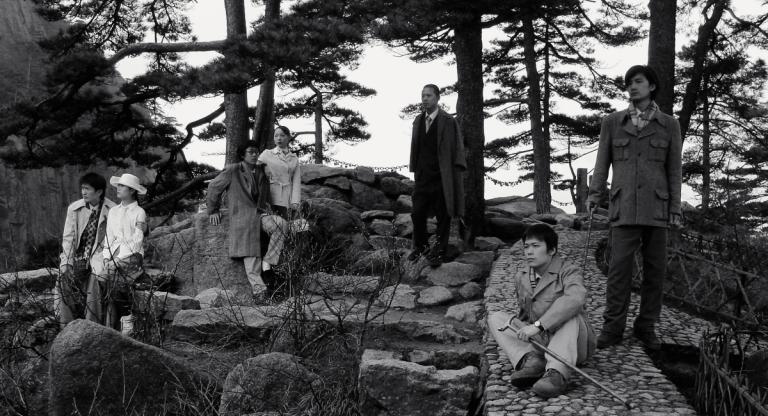

This willful self-estrangement is put in jeopardy when Frank collides with familiar faces from his past, fellow alumni of his childhood orphanage who refuse to let him spend Christmas Eve alone. One of these faces belongs to Lori (Molly McCarthy), a beautiful––and romantically unavailable––young woman who throws Frank off-axis. “Danger signal,” the narrator warns at various moments, imbuing Frank with a spidey-sense for trouble that rarely helps him out of it. So much of his covert work consists of waiting, stalling, lining up the perfect kill, and it’s at these points of standstill that he becomes genuinely vulnerable. Various time-killing side quests prolong and exacerbate the side effects of human connection, introducing glimmers of hope that pull double duty as nails in Frank’s coffin.

Quite possibly the most uses of the word “hate” per minute in any motion picture, Blast of Silence numbs the viewer to this virulence through its unrelenting unification of style and subject. Its poster promises audiences the experience of walking “shoulder-to-shoulder” with a killer and the film delivers on this exploitation premise with the bitter irony of a monkey’s paw. Its dilapidated world is inextricable from the hollowing-out of its human focal point. Blast of Silence’s jagged jolts and rough-hewn emotions build toward appointments with death that carry the bathetic weight of an apocalypse in miniature; it ends with both a bang and a whimper.

Blast of Silence screens tonight, November 7, at Nitehawk Williamsburg on 35mm as part of the series “The Deuce.”