When I met the film critic and programmer Ricardo Vieira Lisboa in Porto, I asked him a few questions about Branca de Neve (2000), which he included in his Sight and Sound “Greatest Films of All Time” list. (His list consists of ten films “without images.”) I asked him about the coat that Monteiro supposedly placed on the camera during the film shoot and the possibility that a few glimpses of light managed to slip through—that there might be an image somewhere in the film’s complete darkness. “The coat story is probably fake,” he told me. “There is nothing to see.”

It is possible that Monteiro found the inspiration to make a film consisting of a black screen in the Robert Walser book that he was adapting. The play itself often mentions silence, invisibility, and death (“I am speechless and imageless”), but it really could have been based on any written work. In fact, the original idea for Monteiro’s project was to adapt Marquis de Sade’s Philosophy in the Bedroom. In the end, Branca de Neve is a film about literature, poetry, and theater, or more precisely, a film about the transformation of the written word into the spoken word.

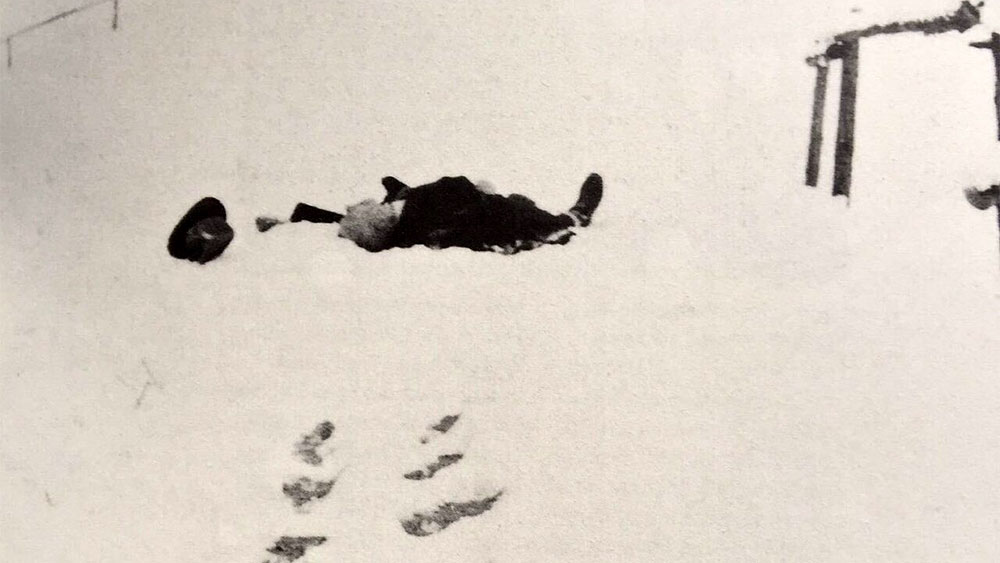

When most of Monteiro’s films were recently restored, the first film that came to my mind was Branca de Neve, not only because it presented an opportunity to see the film’s very few figurative shots in all their splendor—especially the last one, of Monteiro in the forest saying “No” to the camera, but without sound—but because the restoration offered a chance to see perfect blackness, nothing in its original essence. Sure, we do not really watch Branca de Neve, we mostly hear it. But if we do watch it, we witness an oppositional cinema that has only been tried out by the most radical, almost self-destructive filmmakers: Guy Debord (Hurlements en faveur de Sade, 1952), Marguerite Duras (L’Homme Atlantique, 1981), and Nam June Paik (Zen for Film, 1965), to cite a few examples.

Most films are reflected onto the screen when they are projected, such that their light also illuminates us. Branca de Neve is not only one of the few non-figurative films, but it is one of the very few films that produce no light, and perhaps the only one that is still narrative. Tonight at Anthology Film Archives, light will be projected on the screen. But this will be the light of the subtitles, such that the reflected image—perhaps against Monteiro’s wishes—will be the film’s text itself. These subtitles, in a way, contradict the point of the film, which is to experience nothing but the sound of voices—an impurity, as well as a necessity, to make us, non-Portuguese speakers, understand what these voices have to say. And so, it is through impurity that Branca de Neve approaches its impossible end: turning text into image.

Branca de Neve screens this evening, March 22, at Anthology Film Archives.