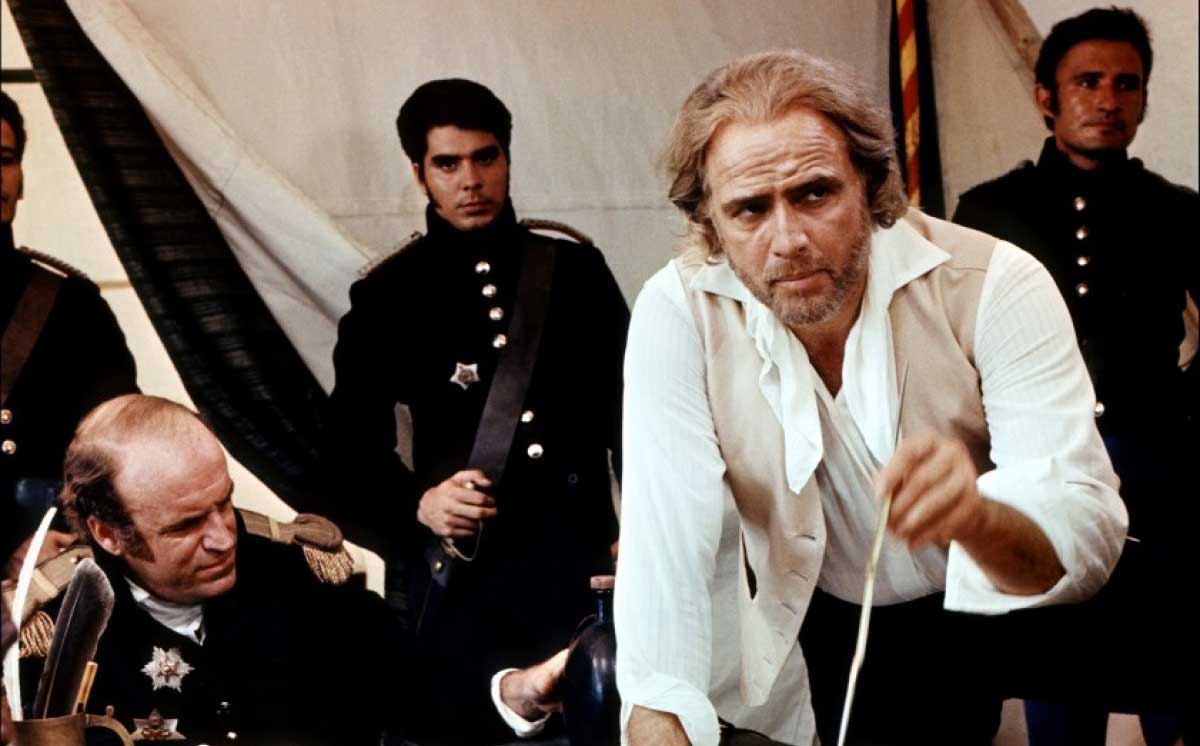

For all the accolades lavished upon The Battle of Algiers (1966), it’s intriguing how little retrospective attention is given to Burn! (aka Queimada!), Gillo Pontecorvo’s big-budget follow-up starring Marlon Brando as a fictional British mercenary called William Walker, named after the real-life American whose 19th century adventurism in Nicaragua and Honduras was later skewered in Alex Cox’s Walker (1987). Pontecorvo’s Walker is an agent sent by the British to instigate a revolution against the Portuguese in the sugar-producing Caribbean island nation of Queimada (“burnt,” so-named after the original colonizers murdered the indigenous population and imported slaves from Africa.) A mulatto politician named Teddy Sanchez (Renato Salvatori, in brownface) is installed to set policies preferential to the British Royal Sugar Company. Walker mentors a dockworker named José Dolores (Evaristo Márquez) who goes on to lead a guerrilla struggle against Sanchez’s administration. Then, Walker is tasked with returning to Queimada to face his old friend Dolores; ten years after instigating a bogus insurrection, he must now figure out how to suppress a real one.

Burn! fits alongside Walker in the slim but fascinating pantheon of anticolonial period pieces that includes Med Hondo’s West Indies (1979), Moustapha Akkad’s The Lion in the Desert (1980), Steven Soderbergh’s Che (2008), and John Sayles’s Amigo (2010). Dizzying, breathtaking sequences include Sanchez’s assassination of the island’s Portuguese-backed puppet government and too-fast ascent to the presidency. Similarly, the exploitative nature of triangle trade is brilliantly illustrated in a scene that depicts the adjustment of sugar prices in the London Stock Exchange ten years after Sanchez’s consolidation of power. The types of massive battle sequences typically left to the likes of David Lean are given a handheld fluidity by Pontecorvo; Walker’s ruminations on brute colonial force and its discontents among the islanders feel like an expansion of the infamous paratrooper colonel Mathieu’s even-handed monologue in Battle of Algiers. Pontecorvo also uses the iris of Walker’s spying glass to stress the nature of his vampiric relationship with Dolores, while distant jacobins on horseback come into jittery focus, serving as a kind of Marxist corrective to Omar Sharif’s introductory scene in Lawrence of Arabia (1962).

The film is also a complicated, quintessentially post-breakthrough movie whose grandiosity is commensurate with the tortured history of its production, which took place in three different continents over the course of nearly a year. Burn! came after Brando threatened to quit Hollywood filmmaking, and Walker is arguably the apotheosis of his career’s first leg, building on his self-interrogating roles in Sayonara (1957) and The Ugly American (1963). Brando cited Burn! among his favorite performances, but also as the most trying shoot of his career; he nearly walked off the production multiple times. In Stefan Kanfer’s Brando biography Somebody, the star describes Pontecorvo as “a complete sadist,” indifferent to the rampant drug abuse among his crew, and a hypocrite for paying the film’s Black Colombian extras far less and feeding them lower-quality catering than their white counterparts—a condition Brando insisted he change lest the whole operation go up in smoke.

Pontecorvo’s film represents a strained and surreal endeavor to locate humanity within established archetypes, and to confront viewers with the bloody toll of globalized capital in the guise of a swashbuckling epic. (At the end of the film’s first half, Walker muses to Dolores that his British superiors are sending him next to Indochina, an all-but-veiled reference to the contemporaneous American quagmire in Vietnam.) Both veterans of spaghetti westerns, screenwriters Franco Solinas and Giorgio Arlorio design Walker as a stand-in for a particularly British flavor of aristocratic colonialism, yet Pontecorvo and Brando remarked on the subtlety of the character, who begins to question his own nonexistent politics during the second campaign in Queimada. Evaristo Márquez, a Colombian herdsman who had never seen (much less acted in) a movie before he was discovered by Pontecorvo’s location crew, deserves special mention for holding his own as Jose Dolores opposite one of the biggest movie stars of all time.

Pontecorvo’s mad dash to make a fictitious banana republic stand in for Third World liberation struggles at large make its signifiers questionable—the freed slaves ululate identically to the Algerian freedom fighters in Pontecorvo’s last film—and its historical shorthand testifies to the compromises of working with United Artists, who insisted Pontecorvo make the Portuguese out to be the film’s villains lest they lose a substantial chunk of the Spanish moviegoing market. All too appropriate that there exists no perfect way to watch Burn! Your options are either an Italian-dubbed director’s cut or the english-language version showing at Film Forum, which runs 18 minutes shorter. While a new print of the extended Italian version began making the rounds in 2004, the english-language Burn! is still worth watching. Not fully bowdlerized, it at least features Brando’s actual voice. He gives Walker a dastardly English accent within which lies another bit of self-reflexivity, as Brando had played the silver-tongued Lt. Fletcher Christian in MGM’s version of the Mutiny on the Bounty (1962) just six years earlier.

Burn! screens tonight, December 24, and December 26, in 35mm at Film Forum as part of the series “Brando 100.”