In 1893, a literal cabal of fruit companies recruited the U.S. government to overthrow the Hawaiian monarchy. Ever since, these archetypal white pillagers and their corporate antecedents have hoovered up the former kingdom’s resources with impunity, using imported cheap labor in their sugar fields, exoticism peddled by Hollywood and bastardized indigenous culture repackaged for tourists. Director/editor/camera operator Anthony Banua-Simon’s debut feature Cane Fire annotates this long, repetitive arc with an impressive array of archival and original material concerning Kaua'i, the “Garden Isle,” which has served as location to over a hundred Hollywood productions. He combines interviews with his own family, footage from Elvis movies, and a gaggle of nauseating promotional materials to probe the material history of an island and its fraught relation to the world.

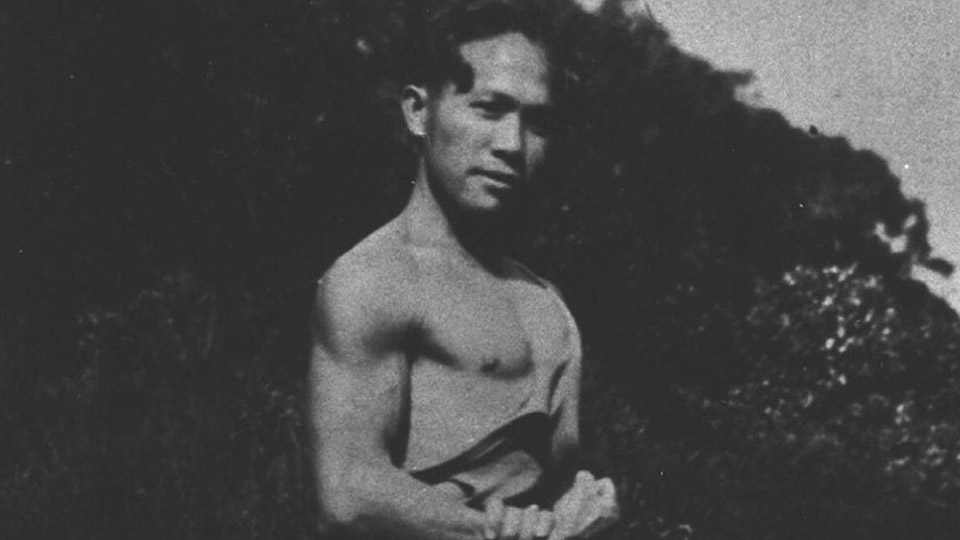

First and foremost, Banua-Simon contrasts the colonial fantasy of Edenic plenty with the reality of the expendable labor pool behind billion-dollar sugar empires and extortionate Mai Tais. Footage detailing the day-to-day existence of three generations of his own extended family documents the transition from an agricultural economy in which labor unions won basic concessions from plantation owners to a service economy’s demands for subservient smiles with little in return. His great-uncle Henry was a proud union man who drove Hollywood bigwigs to set in the 1950s in between stints driving sugar cane trucks, but his grandsons face a burgeoning meth crisis and bleak job prospects. Avoiding such travails altogether are the vultures repurposing plantations into investment properties for wealthy continental Americans. One perfectly-named white realtor, Chad Deal, weeps while recounting a ludicrous story of realizing he was “home” after a native Kaua’ian greeted him decades ago. He now specializes in selling second and third homes to rich idiots who call themselves “locals” because they visit the island one month a year.

When Banua-Simon asks his participants directly if they’re interested in seeing the films shot on their island, he receives mostly shrugs. One key exception is a local musician trapped in an endless loop of stories concerning brushes with celebrity. Not coincidentally, he’s seen late in the film on a witness stand defending a vile developer’s plan to rehab the famed Coco Palms Hotel despite an indigenous activist group’s efforts to reclaim the property, which was built on an indigenous burial site. Their doomed struggle culminates in a court case they can’t possibly win (the developer’s ownership of the land is legally unimpeachable) but nevertheless offers a cathartic moment when the group, acting as their own lawyers, are able to interrogate their persecutor. Slight as it may be, it’s a victory not enjoyed by many on the island since Captain Cook dropped anchor and the swindle began.

Cane Fire is at HIFF through November 29