Con artists have always fascinated filmmakers, who perhaps recognize in their own spectacular sadism a kinship with some of the more dazzling violators of the social contract. Audiences, for their part, seem to enjoy juggling identification with these too-smart operators and the rubes who hang on their every word. Writer-director-editor-star Wendell B. Harris, Jr., toys with this dynamic in his astounding first film, Chameleon Street, newly restored and ready to claim the accolades it deserved upon its release in 1989. Harris spent years interviewing fellow Michigander William Douglas Street, Jr., about the latter’s hilariously prolific rap sheet of impersonation schemes in order to transform a true crime oddity into a lacerating critique of double consciousness.

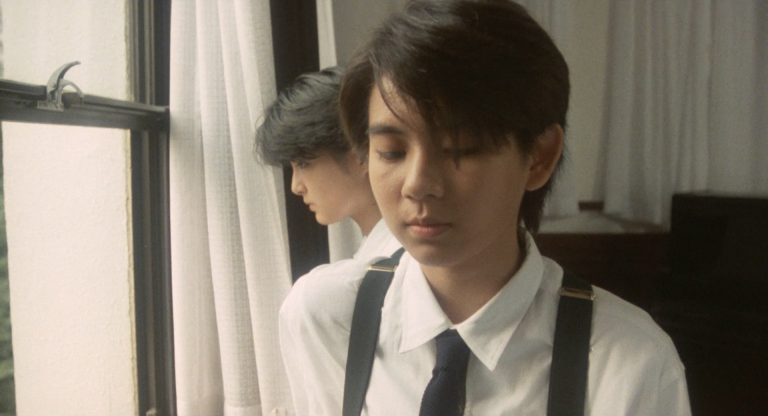

Harris stars as Street, whose poverty, boredom, and brilliance conceive a series of identities that keep his adrenaline up and bank account out of the red. With supercilious affect he performs surgery, matriculates at Yale as a foreign-exchange student, extorts a baseball player, and contributes to Time magazine, while many happy suckers bask in their own appreciation of such an exemplary Black man. Harris avoids any psychological profiling of his character and instead treats the crimes as pretext for an examination of race and authority. Street has no trouble conning administrators eager to see his brilliance as a reflection of their own upstanding racial convictions; it’s those further down the ladder who smell his bullshit. Harris embodies Street as a sneering aesthete armed with an arsenal of cutting witticisms his victims masochistically enjoy. Contrary to contemporary depictions of sociopathy, the film manages a clear distinction between its own charms and those of its subject.

According to Harris, the actual Street saw the film and despised it; his only comfort was the fact that no audience would turn out for something so awful. Perhaps he’s spent the past three decades rejoicing at the film’s initial failure to find an appreciative public, but that had nothing to do with its quality and everything to do with a timorous, incurious industry. Harris left Hollywood after years of pitching to cringing bean-counters, with nothing to show for it except a check from Warner Bros. for the remake rights to Chameleon Street. Few indie-boom debuts so unambiguously announced a major talent, and few what-ifs of the era are more distressing to contemplate than the career Harris should have enjoyed.

Chameleon Street screens October 22–28 at BAM.