Founded in 1958 as a drug rehabilitation program, Synanon was a live-in therapeutic facility, intentional community, and religious self-help ideology, once described by Walter Cronkite as “bizarre even by cult standards.” The group, an outgrowth of an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting in Santa Monica, converted a dilapidated beachfront flat into a wellness center that welcomed addicts and drifters into an intense “attack therapy” regimen. Synanon’s sleek branding was closer to the entrepreneurialism of NXIVM than the bohemian self-searching of the Esalen Institute, with many of its residents even moonlighting as the salesforce for its marketing arm, ADGAP, a promotional gift company that sold custom pens and stationary to local businesses. Marshall McLuhan, psyched as he was on the strange emerging social arrangements of the information age, would likely have been amused. His copy of Lewis Yablonsky’s 1965 sociological study Synanon: The Tunnel Back is among the six thousand titles in his personal library now available for research at the University of Toronto.

Synanon’s origins on the beaches of westside Los Angeles, its business savvy, and its propensity to attract the wandering edges of the entertainment industry made it particularly mediagenic. Early patients included former Our Gang sharpster Matthew “Stymie” Beard and veterans of the West Coast jazz scene such as Art Pepper, Charlie Haden, and Stan Kenton. Robert Drew and D. A. Pannebaker visited the Synanon House in 1961 to film David, a vérité study of a dope-hooked trumpet player, and Columbia journeyman Richard Quine shot his studio hagiography Synanon (1965) with stars Edmond O’Brian and Eartha Kitt on the premises. Later, residents of the compound appeared en masse as extras in productions such as George Lucas’s THX 1138 (1971) and Robert Altman’s California Split (1975). Not unlike the teachings of L. Ron Hubbard, himself a self-styled jazz aficionado, the Synanon program made good use of its sheen and proximity to talent; it had expanded into a network of national franchises within a decade.

In 1968, Los Angeles filmmaker Howard Lester traveled to an unincorporated area in Marin County, where the organization had transformed a former radio station into a large-scale living facility. Assisted by Chick Strand, Lester documented the group’s in-house educational system, a radical proposition that divided kids into small cohorts of their own age group to live and learn autonomously, with minimal oversight by adults. The day-to-day of Synanon was structured around “The Game,” a group therapy exercise that asked participants to engage in unrelenting verbalization of their innermost feelings followed by harsh recourse by their peers. Shot in a freewheeling, even-handed style—some of the footage was even taken by the subjects themselves—Children of Synanon juxtaposes interviews with the group’s leadership about their pedagogical philosophy with images of the compound, its classrooms and playgrounds, and peeks in at upset-looking juveniles engaged in lengthy struggle sessions.

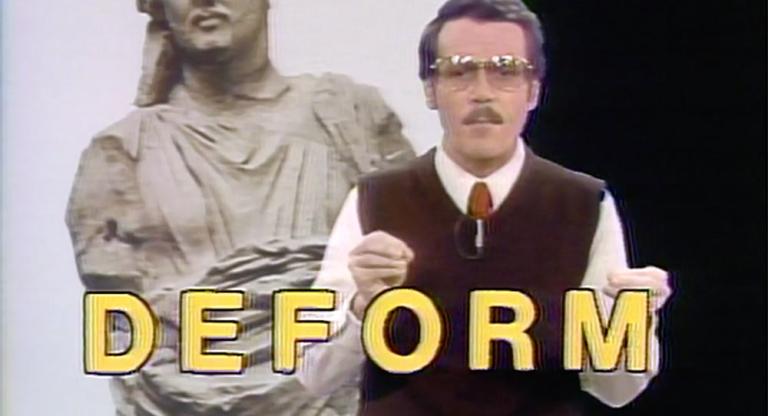

As a snapshot of the zeitgeist, in which schooling was being reimagined, the film fits snugly with The Child of the Future: How Might He Learn, produced for Canada’s National Film Board in 1964. Hosted by McLuhan, the documentary surveys the educational applications of technology by interspersing talking heads from educators and psychologists such as O. K. Moore and Jerome Bruner (a key influence on Synanon’s curriculum, alongside A. S. Neill) with extended pontification by the cigar-chomping media theorist. Scenes demonstrate how closed-circuit television systems, 8mm film, animation, and audiotape were being used in an array of classroom settings, from rural Japan to inner-city Detroit to a prep school in Massachusetts.

“The child of the future is a rather terrifying thought,” McLuhan admits, and frankly he hardly had a clue. Many of the utopian projects that germinated in the anxious postwar landscape had weird, unintended consequences. In the case of Synanon, its sunny promises of the straight life began to falter by the late ’70s, leading to parade of bad press and court cases, the brief imprisonment of Stan Kenton’s son Lance for attempted murder (he had placed a rattlesnake in an attorney’s mailbox), charges of conspiracy and fraud, and finally the group’s dissolution in 1991. Still, traces of its tenets can be found in many contemporary sobriety programs, from Nancy Reagan’s “Just Say No” to the constellation of exploitative, tough-love teen wilderness camps speckled across the United States. The jury is still out on the premise that participatory electronic media can be used to sculpt formative minds into an enlightened citizenry, but there is hope yet.

Children of Synanon and The Child of the Future: How He Might Learn screen tonight at Light Industry on 16mm.

Special thanks to the Filmmakers’ Co-Operative and M. M. Serra for providing a screening copy of Children of Synanon.