In November curator, author, and filmmaker Stanley Schtinter conducted a brief tour of Brooklyn’s art houses and microcinemas in support of his recent book Last Movies, an exhaustively researched chronicle of the final films viewed by notable cultural and public figures. At Spectacle, audiences were treated to thirty minutes of I Want to Live! (Robert Wise, 1958), cut off at the approximate point that Sergio Leone died of a heart attack while watching on television. Later, Light Industry stopped the projection 15 minutes into Burt Topper’s War is Hell (1961), the point at which Lee Harvey Oswald was arrested after sneaking into a screening at the Texas Theatre following the assassination of JFK. As Chris Petit says below, “Cinema has an incredibly high body count,” a truism that extends beyond the boundaries of the screen.

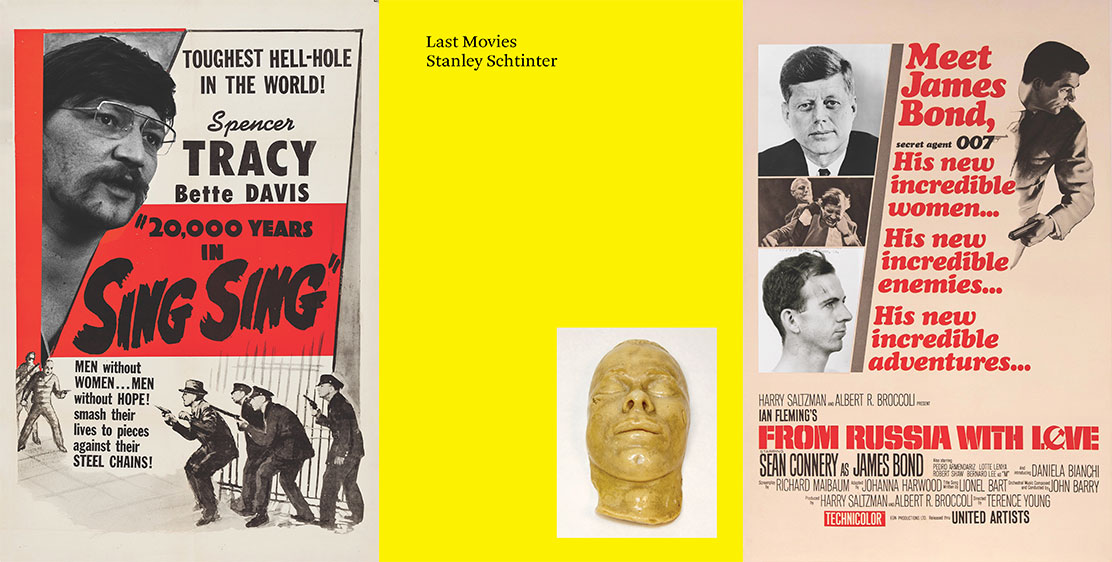

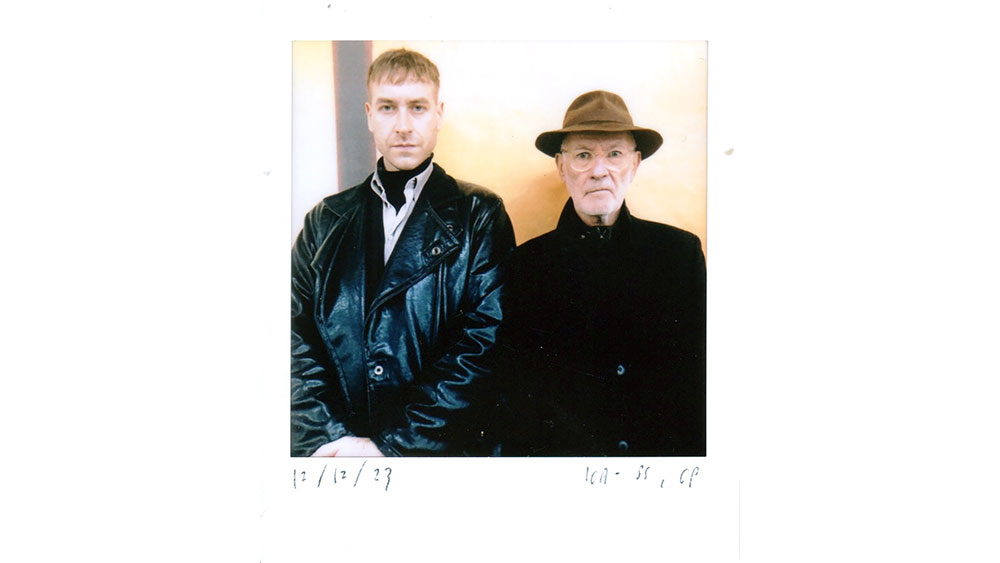

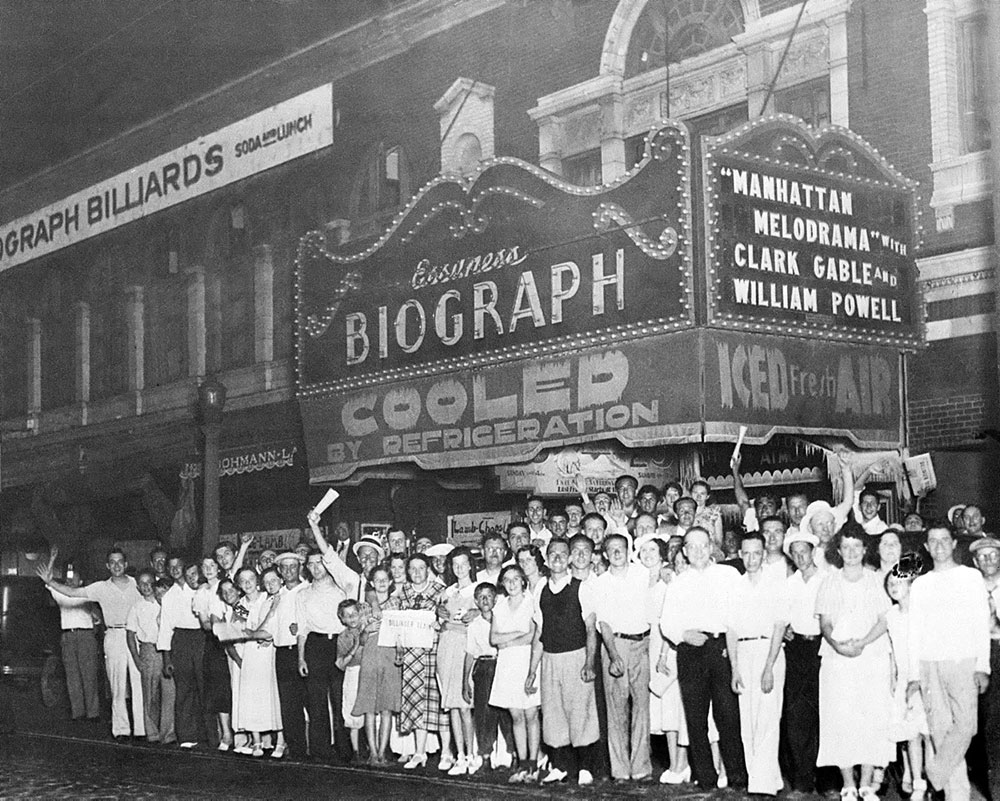

Last Movies continues to sweep Europe: in the next few weeks a four-month series at the ICA in London draws to a close, a new season at the Watershed in Bristol begins, and a twenty-four hour installation edition opens at ZDB Gallery in Lisboa. To mark these occasions, Screen Slate is pleased to run a conversation between Schtinter and novelist and filmmaker Chris Petit (Robinson, Radio On), which took place at the ICA on December 12, 2023 following a screening of 20,000 Years in Sing Sing (Fassbinder’s final film) and Manhattan Melodrama (John Dillinger). Their discussion has been transcribed and edited by Schtinter and Petit for this publication.

CHRIS PETIT: The thing about Last Movies is… there isn’t really much to say.

STANLEY SCHTINTER: I’m not sure it was even intended to be a book. What’s there in print is a sort of incidental over-sharing of possible programme notes. The writing was an attempt to bring some order to the chaos of the possible film presentation, forcing open the drearily academic tendencies of programme notes. It’s up to the audience to consider the perspective of the viewer who last saw the film: be that Fassbinder or Dillinger, be that JFK or Lee Harvey Oswald. That’s the double-header we launched with here last month, on the 60th anniversary of Kennedy’s assassination.

PETIT: Lee buying a coke at the book depository, and then getting to the cinema and buying popcorn?

SCHTINTER: The publisher pointed out early on that this is as much a project about food and drink as it is about cinema and death. Heinz Baked Beans were huge in Ian Fleming’s Bond novels; there’s a long sequence in The Spy Who Loved Me about Bond foraging a can and eating them cold. It’s a product placement that sadly never made it into the films. Coke, on the other hand… even Fassbinder can’t escape Coca-Cola. Bottle after bottle of the stuff in Ali: Fear Eats the Soul.

PETIT: I'm curious to know whether Fassbinder’s films stand up. Have you seen any recently?

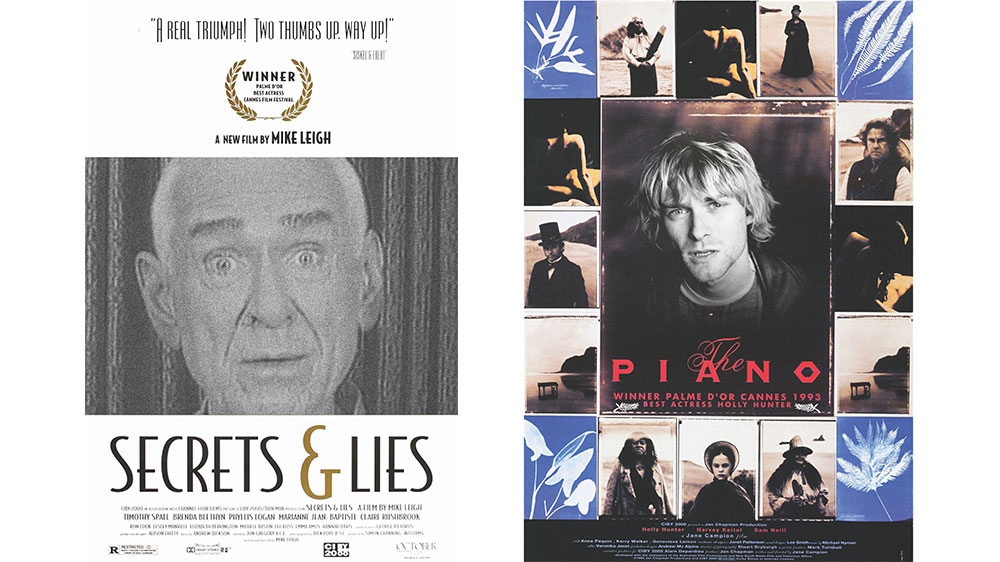

SCHTINTER: I most recently watched In a Year with 13 Moons. 1997 was one such year, and it was also the year William Blake prophesied to be the last. Heaven’s Gate, the San Diego religious group, knew as much, abandoning their earthly bodies to ascend to the eternal spaceship, hidden as it was, so they believed, behind the Hale–Bopp comet. They watched Mike Leigh’s Secrets & Lies last, which might have been the final push they needed. But all throughout 13 Moons I wondered what might have been had they watched Fassbinder instead? By the end Marshall Applewhite (the leader of the Gate-crashers) had withdrawn completely into Old Testament conspiracy, and it was his inability to deal with his homosexuality, and possibly gender dysphoria, and totalising grief at the loss of his creative life-partner, that pushed him into that position. Fassbinder deals with all of this in a way that’s as gentle as it is dangerous. In one scene the protagonist attempts to talk a janitor out of suicide: “You don’t understand,” he responds to her. “Suicide is not for those who want to die, but for those who want to live.”

PETIT: 13 Moons is one of the ones that I haven't seen.

SCHTINTER: Did you ever meet him? Fassbinder?

PETIT: I was with a critic Jan Dawson in Cannes to interview Kurt Raab, who was an actor in Fassbinder's films and also his art director. He'd just been in the film The Tenderness of Wolves, directed by Ulli Lommel. Jan and I sat at the top end of the table with Raab at a Fassbinder lunch party on the beach, and the Fassbinder boys, about fifteen of them, were all in a terrible sulk because we were talking to Raab who was lording it over the table. Fassbinder was in a strop about the whole business and was predictably decked out. It was about 85 degrees. 90, maybe. Leather jacket, string vest, sitting down the other end of the table. There was a cameo from Werner Herzog, who came down the steps onto the beach and had a whispered conversation with a PR woman who handled all of their stuff, and she promptly burst into tears. Herzog left and the table went into even more of a sulk. He appeared again about 15 minutes later, and I struggle even to believe the image, but he came bearing a huge amount of red roses, presumably bought off one of the many street sellers, and presented them to the woman who burst into tears all over again. By this time, Fassbinder was beside himself.

SCHTINTER: Herzog’s cameos in this project—and it’s important to remind everyone I don’t have control over any of the characters and cameos—are probably only rivaled in quantity by James Bond’s. As maker, traveler… Bruce Chatwin sees Herzog’s Herdsmen of the Sun. Chatwin, close to death, hoped Herzog could repeat the epic journey by foot he undertook for Lotte Eisner, his mentor, close to her death, and save him. There's also the famous story of Joy Division’s Ian Curtis watching Herzog’s Stroszek on the night he died. He probably did, but Cape Fear was on TV afterwards, and then international golf highlights. I suspect he did them all, and the letter he left behind tacitly supports this. You were telling me a good story about Herzog earlier?

PETIT: Werner had been away, traveling, making films, during which time his long-suffering wife had an affair. Werner came back to this, and there was a row which involved gunplay, and as a result when he went to Cannes he was being kept in the hills by the German contingent and barely showing his face, except at the German reception, which was one of the big parties. Everyone was told: don't mention the shooting. As it was, no one was talking to him but I knew him slightly, in fact I think I was the first person who ever interviewed him in the UK for Aguirre when he was like he always is, so when I mentioned I'd worked in forestry in Bavaria, he said, ‘Jah, jah, it’s good to work with the hands!’ But to go back to the Cannes party, he was standing on his own so I went up and politely asked, 'How's it going?' And he said, ‘Jah, jah, there was a shootout,’ at which the whole room went quiet. And I asked, ‘What happened?’ And he said, 'I hit the lintel.' The doorframe. So I said, 'Well, I'm extremely impressed that you know the word lintel.' And that was the end of our conversation.

To go back to Lee Harvey Oswald, if anyone can explain to me... I mean, did he act on his own or did he not? You get an interesting correlation between conspiracy and drift, which really are at the opposite ends of the spectrum. Was he part of the conspiracy or this ultimate drifter? What I don't understand in the whole story is how you make what they call the patsy angle work, in terms of setting it up, as in really, really work? What exactly was the frame and what was his position? What did he expect? And to go back to the popcorn, and it gets complicated after this, there is a story that there were two Oswalds in the cinema, and you get into the whole Oswald double thing. There was apparently another Oswald driving around in the weeks before, which is interesting because Lee couldn’t drive. And just as a side track: when he was a marine he got into an argument with a sergeant, and he smashed his Johnny Cash record, which I always thought was a significant detail. On the day before the Kennedy killing either Lee or the other Oswald went and bought a ticket to a Johnny Cash concert taking place on the Saturday night at the Sportatorium, which was canceled. But to go back to the popcorn. It was rumored that the Oswald who made that final purchase was in fact not Lee but the other one, who was up in the gallery when Lee was downstairs. And the story was that one was taken out the front, arrested by the police, and the other one was snuck out the back. Now, how does that work as part of the patsy angle? Why do you have to have two Oswalds in the cinema? I have no idea but there are screeds of stuff on this material. Anyway, I hope he enjoyed what he saw of the movie War is Hell. You reckon about 15 minutes.

SCHTINTER: War is Hell is an officially "lost" film, which is weird because it had huge distribution, especially after United Artists took it on to screen as a double-bill with JFK's likeliest last, From Russia with Love, when that film was eventually released. (JFK had seen an advance copy.) This good humored if macabre marketing stunt, riffing on the strong-man image JFK cultivated and Oswald’s Communist past, was central to this project's inception. In the only available copy of the film, lasting about forty minutes total, there's a convenient scratch in the celluloid around 15 minutes in, just after the long opening and the credits. The image curls and collapses through a stroke of black into bright white. I figure this is the moment the police busted in and took out Lee. The timing works. The B-movie then, the living matter of the celluloid, is shocked by its sudden, unexpected appearance in… history. When War is Hell is shown as part of the Last Movies programme we cut it at the point we can say the character would have stopped their viewing, in Oswald's case due to the arrest, or others due to death. Sergio Leone dies watching Robert Wise's I Want to Live. Not far from here a cartoonist called Mel Calman died at the Empire on Leicester Square. He was watching Carlito's Way, and had a heart attack at the point Pacino's Carlito spares his eventual killer, Benny, the same fate. He commands his henchmen to "Just Do It!" As in let him free... I couldn't resist but cut at this point because it establishes a perfect segue to Heaven's Gate, with its 39 crew members famously ending their lives in brand new matching Nike trainers, giving the company's “Just Do It” motto an unfortunate suicidal edge. For what it's worth, I think of their final collective act as an artistic rendering of Revelation to rival any other.

The shoe-store owner opposite the Texas Theater called the police because he saw Oswald skipping into the cinema for free. What if he had paid? The purchase of the popcorn I don’t believe. If he’d snuck in to the auditorium for nothing on that afternoon of scant attendance, was he really going to emerge back into the foyer to purchase some popcorn? Of course a fair point could be that . . . he might have really, really wanted some popcorn and not had enough cash for both admission and the popcorn, but . . . I don’t think so. It’s hard to know what really went on in there. There was a wheeler-dealer manager at the cinema who almost certainly sold the chair that Lee wasn’t actually sitting in for the premium of the assassin’s sweat, and the cinema still today does business on Lee’s final film there. There’s a chair named after him, but architecturally inside the place it’s totally different.

PETIT: Who do you think got the best movie?

SCHTINTER: The ones tonight are pretty good. And specifically here at the ICA, as we've got an original 1934 print of Manhattan Melodrama. It's a pre-Code picture and so is 20,000 Years in Sing Sing. I expect Fassbinder would've liked his accidental union with John Dillinger through Sing Sing on film. The connection? In the earlier film Fassbinder watches last there’s a sequence in which a minor supporting role, Blackie, stares confusedly into a mirror. “Leaving us tonight, Blackie?” Taunts a prison officer passing his cell. “Not tonight,” responds Blackie, resuming his confusion with the mirror. In the later film seen by John Dillinger, also set at Sing Sing prison, though it obviously has nothing actually to do with the other, Blackie is the name of the leading role: we can say then the inmate finally “finds his face” in Clark Gable. When this Blackie is betrayed by his best friend, Jim, the prosecutor in the film, there’s a long sequence justifying Jim’s betrayal through the perceived lawlessness of Depression-era America; through the crimes of Dillinger and his like. This long courtroom sequence was later significantly cut down and didn’t make it into digital restorations, so you need to see an original print to get it. I don’t know why.

Dillinger's death more or less coincided with the introduction of the Hays Code, Manhattan Melodrama narrowly beating it into existence, which would restrict what could and couldn't be shown on screen. No coincidence. J. Edgar Hoover intended to control cinema to his own benefit, to create the kind of law enforcement agency he wanted. You can trace what the FBI are today directly to that moment. The potency and power of cinema, however, became too great. Killing Dillinger wasn't enough. He was educated by prison, in the way Malcolm X spoke fondly of, and the movies, when the outlaw's virtue was the thing. The law had to restrict what could be shown.

I think 20,000 Years in Sing Sing is excellent, too. As I said, Bruce Chatwin watched Herdsmen of the Sun, the Werner Herzog film about the Woodabe people. This is very beautiful. Brannigan by Douglas Hickox by contrast is not. Total shit. Unforgivable, even with the cameo of Tony Robinson being thrown into the Thames. The BFI recently splurged your tax money on a blu-ray release of it. John Wayne is a police officer in Chicago, and he comes to London to extradite a gangster. Peter Sellers watches this on the other side of Saint James' park, where we are now. He was holed up at the Dorchester Hotel and effectively died there. He saw the film premiering on TV, and would have paused to view the uncanny camera’s descent onto the Dorchester, where the film’s villain is staying. The villain leaves the hotel, crosses the park, and walks up the very steps that flank this cinema, for breakfast in Soho.

Audience questions?

Audience member (Adam Feinstein, authority on Michael Curtiz’s life and work): Stanley: in the book you speculate about whether if Fassbinder had been watching Michael Curtiz's Flamingo Road instead, with the upbeat ending, he might not have died. But actually, seeing that's the ending of 20,000 Years in Sing Sing, of course, which is very Double Indemnity. It's straight out of Double Indemnity with the homoerotic—perhaps—overtones that people read into the end of. What do you think Fassbinder made of the other ending? Did he say anything about that? And the other thing is, you mentioned the date. Coincidence of a date. What? I've seen this film quite a few times, but the emphasis on Saturday, on not doing on Saturday. Bette Davis was born on a Saturday. And she hated Curtiz. She loved Spencer Tracy. They were both born on the same day. They shared a birthday. But anyway, the ending: did Fassbinder ever write about the ending of Sing Sing?

PETIT: He never lived that long.

SCHTINTER: Exactly. Sing Sing’s celluloid ghosts gave Fassbinder’s body subliminal permission to join them. He became cinema, like Dillinger had before him. It’s unclear whether that night was his first viewing of the film or one of many. He did write an essay about Curtiz, titled “Michael Curtiz – Anarchist in Hollywood: Unorganized Thoughts on a Seemingly Paradoxical Idea.” In this he "confesses" to no great knowledge of Curtiz's work, and no biographical insight. He says that he's only seen about a dozen of the films. Flamingo Road was his favorite, starring Joan Crawford. She's great, and the story is too, but I think the book is far superior to the film. The film weirdly removes the race element of Crawford’s carny girl, which is key. It isn’t hard to imagine Fassbinder really brilliantly remaking it, in the way that he did Sirk in Ali, Cokes, popcorn, and all. Also, Sing Sing was based on the actual memoirs of the prison warden…

Audience member (Adam Feinstein): He gave the permission for the film to be filmed there! The same warden was still there.

SCHTINTER: Later, when Bette Davis was asked about the death of Joan Crawford, she said... You shouldn't say anything bad about the dead. Joan Crawford is dead? Good.

Audience member: What do you get out of stalking the dead?

SCHTINTER: Have you read the book?

Audience member: I'm allowed to ask a question if I haven't read the book.

SCHTINTER: The cinema is the stalker.

PETIT: In the end I think all cinema becomes about death, just through the mechanical process of reproduction. And the people who were there in it are no longer and that becomes more pronounced as the history of cinema develops. Roland Barthes makes the same point on photography. There is a photograph of a man who is condemned to die, so he's both about to die and he's dead. I think cinema is a very deathly business. Talk about stalking the dead. Cinema has an incredibly high body count. I mean, how many people has it killed in its history? Starting with the extras, and I don't know what to make of it, but the act of death in film, any action film the body count is phenomenal, and I've never really seen the matter addressed. I think there's a very patient gentleman waiting to ask a question.

Audience member: I don't know if I remember this correctly, but I think in JFK, the film with Kevin Costner, he plays some sort of detective. And I wondered if we could for a second imagine that that filmic world was allowed to continue. If we maybe think that Kevin Costner had the cajones to find out what really happened on that dreadful day on the grassy knoll, or do you think maybe he wasn't the person for it.

PETIT: I think the problem with the question is: the point of the cover up —and undoubtedly there was one — is that at some point it has to stop making sense. The answer has probably already been provided but the cover up just goes on so you miss the answer. I've wasted far too long on it. I think it's pretty obvious who was responsible, but there's no proof because there's no paper trail.

Audience member: So, so maybe the film, JFK, was actually funded by the FBI in order to really put the nail in the coffin?

PETIT: Anything is possible.The only thing which you cannot dispute or no one has disputed yet is the fact that Jack Ruby shot Lee Harvey Oswald. So I'm trying to work on the theory that maybe he didn't.

SCHTINTER: JFK the movie is total fiction, and yet it has somehow become a legitimate part of the story, so mixed up and confused as the whole thing is. But you said you spent a long time on it. So what do you think? What do you think happened?

PETIT: You don't have to look much further than the CIA. The CIA had a secret policy of regime change abroad. It was basically the tool of a wide range of vested interests represented by the American establishment. I rather like the fact that Allen Dulles, who was head of CIA at the time, or rather wasn't by then because he'd been fired by Kennedy for the Bay of Pigs fiasco and Kennedy had said, ‘I will smash CIA into a thousand pieces’ — anyway, I'm very struck by the near rhyme of Dulles and Dallas, and I think that's your clue. That's the extent of my detective work.

Audience member: It's a Hays Code question. Looking at that film now, I'm not completely convinced about the radical impact of the Hays Code thinking in particular films. The core morality of this film means that it probably could have been made post-code? And I was thinking: James Cagney in the classic Public Enemy role. I mean, he could have easily played Spencer Tracy's part.

SCHTINTER: He was due to play it.

Audience member: What distinguishes Public Enemy from Angels with Dirty Faces, is that in the former its rival gangsters who kill him, whereas in Angels its the state who take control of the death. He's come to justice either way, though the latter has this sort of morality to it possessed by the state. The state then post-Code is the final arbiter of life and death, but so it is in 20,000 Years in Sing Sing? So it has a kind of post-Hays Code feel about it, and I'm struggling to think whether there were definitive differences between them. The sexual side is another matter, but in terms of justice and retribution?

SCHTINTER: But Spencer Tracy's character is in control, right? I mean, at the end, it is the prison warden whose hand trembles, who can't stand it. Although the warden wields the power as a representative of the system that incarcerates and kills, it is as such a rotten and incomprehensible kind of power when pulled into focus like this. Tracy takes possession of his fate. Confronts the charge. And I think that the strictures of the Hay's worked in often more subtle ways. Curtiz's Casablanca is case in point. The ending had to be changed. Early in the film the relationship between Bogie and Bergman was possible because she thought her husband dead. Discovering then that this wasn’t the case meant that her and Bogart couldn’t possibly end up together.

Audience member: All married couples need to be united.

SCHTINTER: Exactly. Bogie and Bergman were meant to end up together in Curtiz’s telling, but the Hay’s prevented this from being the case, giving us the ending the film is known for. You know, Casablanca is the one through-line of all Presidential viewing habits. Kennedy’s favourite, Obama’s too. In the 90s, Trump was in a fierce bidding war for the “Play it again, Sam,” “You Must Remember This” piano used in the film.

As we draw to a close, I want to bring your attention to the playlists compiled as part of this project by DJ Tippit (DJ being the black mirror of JD Tippit, the police officer Oswald was pursued for the murder of before he was linked to Kennedy’s). If you [follow this link] you’ll get to Tippit’s YouTube profile. There there is an accurate list of songs from Fassbinder’s films that were played at his funeral; there is an imagined playlist for the after-party at his favorite gay bar (featuring mostly music from Curtiz’s films, including Casablanca), and another yet for the comedown on Monday morning (all of the saddest songs from Fassbinder’s films). Finally, there’s a playlist compiling for the first time all of the songs Elvis sang about food: “Do the Clam,” “Song of the Shrimp,” “Vino Dinero y Amor,” “Old MacDonald,” among many more.

Last Movies is written by Stanley Schtinter and published by Tenement Press. The parallel film programme ends its current residency at the ICA in London on 12 March 2024, with Schtinter and CM von Hausswolff in conversation. Subsequent events are taking place each Sunday at the Watershed in Bristol, with a twenty-four hour installation edition of Last Movies at Galeria Ze Dos Bois in Lisbon on 23 March 2024.

Stanley Schtinter has been described as an ‘artist’ by the Daily Mail, as an ‘exorcist’ by the Daily Star. Recent projects include The Lock-In and Important Books (or, Manifestos Read by Children).

Chris Petit has been described by Le Monde as the Robespierre of English cinema. His films include Content, Radio On, and The Falconer. His books: Robinson, The Hard Shoulder and Ghost Country.