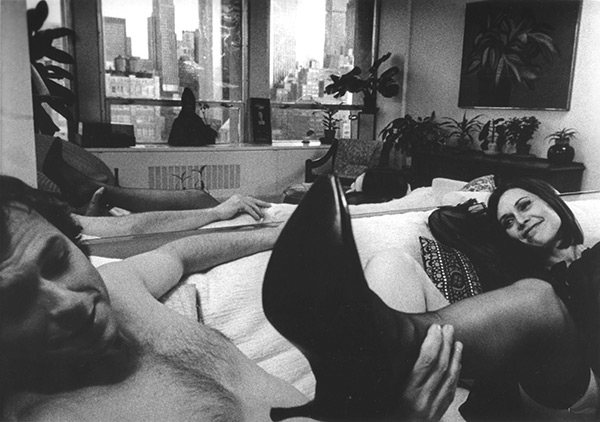

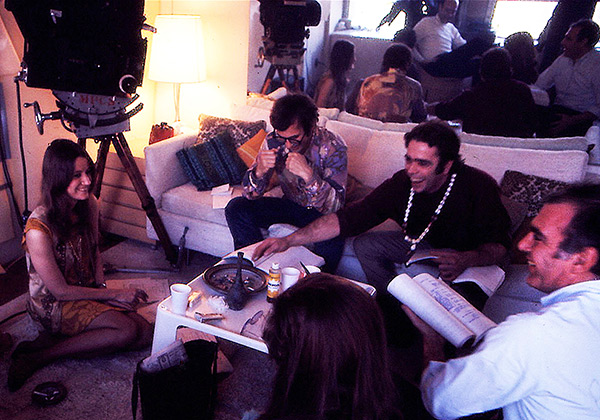

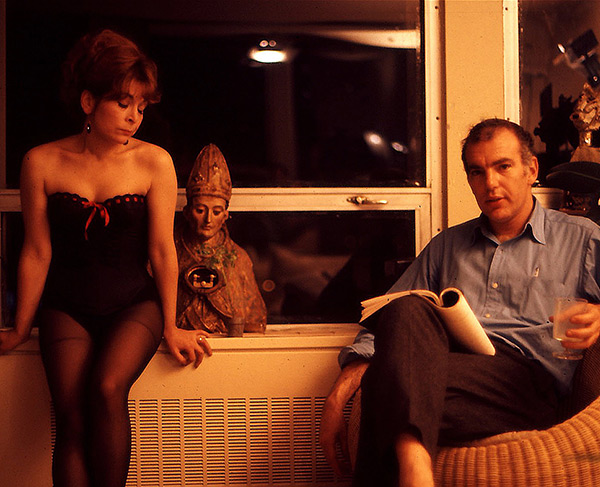

All production photos courtesy of Milton Moses Ginsberg.

Something of a cause célèbre in the local film rags and cognoscenti press, Milton Moses Ginsberg’s Coming Apart was heavily publicized as a zeitgeist picture, piggybacking on the success of I Am Curious (Yellow) by teasing X-rated action while positioning itself as a heady bummer trip for the arthouse set. In a rare lead role, Rip Torn plays a Kips Bay psychiatrist descending into psychosexual maelstrom, setting up a hidden camera in his practice to document his trysts, benders, and meltdowns. Since it is structured around vignetted encounters—Torn patienting a nymphomaniac, flirting with a neighbor or McGovern campaigners, confronting an ex-mistress (Viveca Lindfors)—we’re not directly told why he’s gone to the trouble of documenting his breakdown. It could be a fetish thing, or a self-administered pseudo-psychological study, or, most likely, he could be trying to reconcile his lost grip on reality by outsourcing it to the camera.

More than its fellow late-’60s voyeur films like Jim McBride’s David Holzman’s Diary or Brian DePalma’s Hi, Mom, the static, occasionally inopportunely-framed shots of Coming Apart bring to mind the unsettling yet familiar experience of watching a security cam, or being confronted by an empty room while someone grabs a glass of water on a Skype call. Its most harrowing moments are its most mundane: lulling room tones, barely on-screen action, mumbled dialogue, fumblings to turn on and off the camera. While content-wise Apart is not dissimilar from the middle-class domestic dramas of Faces or Euro-modernism, it formally corresponds more closely to net-era atrocity spectacles like the live-streamed break-up of Internet entrepreneur Josh Harris, the lunatic video-diaries of Björk stalker Ricardo López, or the explosion of multiplex found-footage horror ‘90s onward. (Perhaps it’s worth noting that the same week the film debuted, web precursor ARPANET sent its first successful communiqué—LO for ”login”.)

The interest surrounding the film was punctured by a string of harsh reviews accusing Ginsberg of simply putting "the gloss of culture on his grind movie,” as Judith Crist put it, most notably in a widely-read dismissive write-up by Andrew Sarris in the Village Voice. But with the themes that might have seemed overdetermined in 1969—gender relations, the crisis of psychiatry, compulsive self-documentation—barely having faded from the consciousness, and its barebones visual and performance style proved more than a gimmick by the acceleration of bare-knuckle independent cinema in the years to come, Coming Apart can now be seen sans hype-poisoning as stark and timeless.

Fifty years on from its October 26th opening, the film plays as a special one-night engagement at Metrograph with Ginsberg in person. On the occasion, I chatted with the filmmaker in his Upper West Side apartment, charting how the film was made and the cultural climate of ‘60s New York.This interview has been edited for length and flow.

OK, to backtrack: you graduated from Columbia. You studied with Lionel Trilling?

Yes. And a fellow named Meyer Shapiro, who taught fine arts. His classes were so intense, you had fallen behind by the third lecture. Trilling was great. So was a guy named Dupee, a Henry James scholar. I took a course with Quentin Anderson, Maxwell Anderson’s son, who taught American literature. In those days I was overpowered by Faulker. I didn’t read them until the last year. I was stunned by the quality, the depth of his writing. This guy in Mississippi writing novels on par with Joyce.

You came out of working in television, and you also benefited greatly from the rich arthouse, international cinema scene in the city at the time. I think you can see both of those poles in the film.

In 1960 I saw L’Avventura and La Dolce Vita in the same week. I hadn’t been going to the movies at all. And later another film that affected me profoundly: a guy named Ernnando Olmi was making films, and one of them was The Fiances, which I think is a masterpiece. I saw these films and thought maybe that’s something I could do. These guys were crystallizing the same kind of emotions in film that I had only seen and felt in the novel before, so maybe I could do that. As hard as writing fiction was for me, getting into cinema and writing for cinema came very naturally.

How did you move into film editing?

I got jobs initially. I got a job right away as an apprentice editor at NBC News. They were establishing a documentary unit along the lines of Leacock, Pannebaker, and Maysles. I was an apprentice on a kid's show in that unit, and the editor started giving me more and more work to do. He saw that I was very capable. He said, well, I'm going to treat you as an assistant not as an apprentice. They made me an assistant, and about three or four weeks later I hear that Pannebaker and Leacock looking for editors. So I applied for the job.

[My boss] said, “Listen, you don't have an assistant. I'd like to give you an assistant. Teach him what you know.” So he brings this kid from England named Ridley. I was still very young. I was in my twenties, the kid was in his twenties. His name was Ridley Scott.

We worked together for about two days and he says, “Hey man, you're the greatest. I love this. I'd like to show you some of my photographs.” So I say, “Look, really, I'm under the gun here. I gotta deliver this thing in a couple of weeks.” I’m scared, I've never been full a full editor on anything. So I said, “I'll look at your photos after the screening.” I'm thinking, what is this? This British kid’s coming to New York, going down to the subway with his Nikon, you know, taking these high contrast black and white pictures of people in the trains or whatever—lovers, bums, whatever. I said, “Look, Ridley, I'm very anxious to see your photos, but please don't bring it up until after the screening.”

Finally we have our screening. It goes very well, we all go out for a drink. It's a Friday afternoon. I came in the next morning and the room was filled with his photographs. And the photographs were stunning.They looked like the photographs of Cecil Beaton. I said, “Whoa, I've got to tell you something, but please don't whisper it around. I should be your assistant.” Unfortunately, I never acted on that impulse.

And meanwhile, you’re working on your own material.

Basically, my mind was on the Italians. I wanted to make films. I began to work on screenplays. By then I really knew my way around film. I was shooting and doing camera gigs. I got a job in 1966, the Supremes were going on an Asian tour. I wrote a script just after I got back in ‘66 from Japan. It was optioned. It was cast with Ben Gazarra and Lee Remick at the time. These producers were handling it, and I was so energized that I wrote another, a wonderful screenplay called High Flying Bird, and they optioned that the day I gave it to them.

Writing was a very turbulent business for me. It was always very emotionally turbulent. I was living up on the 76th and Madison. I used to use the library in the Metropolitan Museum to go in and write, because there'd be people around, but you couldn't talk. It comforted me, having company, in a manner of speaking.

What were the two optioned scripts about? Anything that bled into Coming Apart?

The first one was called Lady with a Pink. It was about a young man who was an art restorer for a museum—a dark romance. The next one was High Flying Bird, and that one was much more interesting structurally. It was about this young guy who wants to make movies, who takes money from some very bad people, some mafia people, to write a porn film. And instead he writes a film about a young man who takes mafia money to write a porn film. So it was this “birthday cake” structure so to speak.

About two months in, [these producers] said, “Look, we're not getting anywhere with your screenplays because you insist on directing them,” which I had. I said, “Well, why don't you give me some money? I'll shoot a scene from one of them.” They asked me how much I would need, and I said $20,000. Then I said, “But if you doubled it, I'll write and make a whole film for you for $40,000.” And that was Coming Apart.

What went into the film, culturally speaking?

As you say, things were happening in New York. There was a theater in the mid-Sixties called the Charles Theater. They would show underground movies there, and literally you’d come in with your reel, send it up to the projectionist, and sit in the audience, waiting for your film to come up. You always knew whose film it was, because they'd stand up and applaud. There was some great filmmakers like Maya Deren. People did documentaries on the subway. I had made a documentary on the subway and I brought it in and they showed them.

There were other factors. Andy Warhol was a factor. I was intrigued with Chelsea Girls. I thought in one sense, compared to the Europeans, it was dreadful filmmaking, but there was a rawness to it that was very attuned to the culture I was experiencing at Max's Kansas City. I used to hang out at Max’s Kansas City every day—used to close the place. I used to see Warhol with his entourage of drag queens sweep into Max’s every night around midnight, heading for the red room in the back. He had grown wan from the Valerie Solonas shooting, which had haunted me.

And then suddenly there was hardcore porn showing in theaters in New York. I remember going to see that. I went in, I said, “Oh my God, I can't believe this.” They were actually showing people doing it. And let me tell you, it had power. It was pornographic power, but it had power. It was a significant form of human behavior, and suddenly it was on the screen. I said, “Jesus, I want to do that.” Not in that form, but I wanted my films to have that, and I wanted them to have what Warhol's film had.

Somebody I was going out with who was a young film editor—she saw a film called David Holzman's Diary and said, “You have to see this film.” That really cinched Coming Apart. You know, diary form. That's what I was looking for.

And my personal life, which is probably the biggest factor. I've never said this in interviews—all of those scenes that I wrote were based on incidents in my life. Including the dark character who played Joanna, the Sally Kirkland character. I was hanging out in East Hampton with a group of psychiatrists. I was seeing a psychiatrist who was older and brilliant, but I was hanging around with younger psychiatrists in the Hamptons who were leading the same life I was leading. Promiscuous. And without being aware of it, I had begun to realize this promiscuity was a two-way sword.

How did the casting come about?

I had wanted Rip Torn for the first film, though we got Ben Gazzara. I called him again, I said, “Look, Rip, it's me again, sorry to bug you. I have this script”. He said, “Is there a male lead in it for me? I'm tired of backing up Paul Newman.” I said “You’re in every frame. It's dark and it's erotic.”

During the early sixties, I was living on Christopher Street. There used to be this flashy girl who'd walk in front of my building, and I developed a crush on her. Then I realized she was an actress after a while, found out she was an actress and her name was Sally Kirkland.

She was a part of LaMama, and also had some peripheral Warhol affiliation.

Yes. LaMama, that was the theater I was going to. I actually saw her in a play before I cast her, by Terrence McNally probably, about an assassination.

I think Sally's performance in Coming Apart is the greatest female performance I've ever seen. And maybe Rip's is the greatest male performance. A little prejudiced here — maybe Brando in one or two films. Their performances are great, and Sally is pure Actor's Studio, Method to the core. She comes in, I look at her script and it was like the Talmud. There was my text in the middle, but there was enough space on the outside—she had written in various colored pencils all around the emotional triggers for each line.

I said to her, look, “Sally, I know you're a method actor. I know how you work, but I'm going to ask you to do something. After you work up to a line and you deliver the line, I want you to let the work go and don't speak again until you build up again.” I'm not sure what I was telling her, but she understood. Years later she said I was trying to anchor her in real time, which I did. There's an authenticity in Coming Apart. You know, sometimes it's tough on an audience. You're getting a lot of darkness and eroticism, but you're getting a lot of slow playing out in things too.

I had an afternoon where I was just hitting all of major New York publications, reading the reviews of Coming Apart. You can tell it's bad PR because a lot of the reviews are responding to the press and not the film.

The producers hired a dreadful PR guy. A dreadful human being—sick–before they found the right one. It really got us off to a bad start with a lot of press.

There are a couple of good ones. Richard Schickel, who I've always admired, loved the film. And then Gene Siskel wrote a review about suicide. He says in his review: “If you’ve never considered suicide, the point of this film might go way over your head.” Which scared the shit out of me, but he was right. I mean, it was about despair. Siskel got it. And there were other reviews.

So the film opens, the press rolls out. Sarris’s review is really harsh. Do you go to any of those opening screenings?

It’s hard for me to look at the film. Because I lived with it in an editing world for 5 months, it’s hard. I stood outside one of the theaters on opening night. People are coming out of the theater. This guy comes out, I say, “Sir, how was the film?” He says, “Piece of shit, don’t waste your money.” Then a couple come out. I say, “How was the movie?” And the guy says, “This was the greatest movie I’ve ever seen in my life.” And the girl says, “Actually we’ve just sat through it twice.” And I thought to myself, that’s my focus group, I’m getting out of here.

That’s the way the response to the film was. The response was great among the people I hung out with. Max’s Kansas City types, psychiatrists, artists. Nobody disliked the film except the reviewers.

Was that your apartment in the film?

I lived there. In fact, I continued to live there for about five years. I moved into the apartment to make the movie—literally, I was looking for an apartment with that kind of window and light. Initially publicity was so great, they wanted to evict me. But I explained, “Look, the paper said I filmed it here, but you can’t make a film in a studio apartment!” And they were convinced.