A human gene sequence, as it is glimpsed scrolling across the frame in Mary Helena Clark and Mike Gibisser’s A Common Sequence (2023), is a daunting sprawl of capital and lowercase letters depicting our DNA’s nucleotide bases. The scans of genetic information in the film reminded me of what happens when you open an image file in a text-edit program: human sensory information converted into a computational spew of characters. And yet both are still, technically, a representation of the same thing.

A Common Sequence is an investigation into the privatization of biology—when an apple, the regenerating limbs of an axolotl, or the genetic makeup of a human being is turned into ones and zeros (or As, Cs, Gs, and Ts) can it be owned? Can it be patented? Mary Helena Clark’s more experimental work usually concerns parceling narratives into a form of cryptography, multimedia puzzles with no clear solution. Despite this film being more straightforward and ethnographic in form, the translatory topic fits her filmography well.

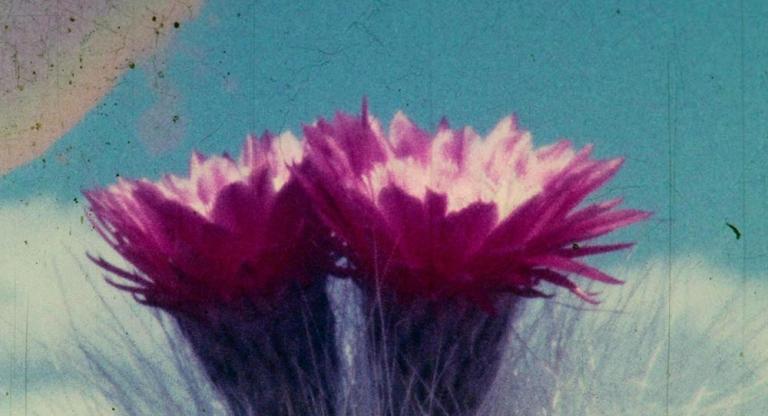

The film has a mutative structure, one segment associatively linking to the next. It opens at Lake Pátzcuaro in Mexico, once well-stocked by a now extinct species of axolotl, which served an important function in the local economy. A nearby convent harvested “syrup” from the amphibians and sold it for its purported medicinal properties. The convent is lined with murals of the hand of God presenting an axolotl in his palm, and a painting of Jesus waving to a fishing boat. Now that the local species is extinct, the nuns raise a limited amount of axolotls in captivity. The film’s disembodied narrator explains the paradox of the axolotl—its regenerative mysteries have turned it into “probably the most widely distributed amphibian worldwide,” with even the Department of Defense importing them for study. However, the captive axolotl have genetically deviated from those originally found in Lake Pátzcuaro to the point where they are essentially a different species.

The film transitions to apple orchards in Washington State, where the jerky, kinetic limbs of a hulking machine grasp for fruit. By describing the “number one apple” to an artificial intelligence, a researcher at Washington State University tells us, the program can devise unique, unnatural combinations of tree grafts to be patented and planted. The AI’s data set is seen in flickering montage, endless rows of apples pulsating before an uncanny eye. The film’s third sequence introduces an Indigenous scientist from the Native BioData Consortium giving a presentation on “data sovereignty.” He argues, chillingly, that attempts to make genetic data openly available are a means of creating an information-rich reserve to be exploited. Researchers consider Native DNA valuable, and although the United States overruled a patent decision in 1995 that allowed for the private ownership of a human gene sequence, these laws do not apply to synthetic sequencing—as soon as the sequence is removed from the human host, it’s fair game.

It’s disquieting, and more than a little foreboding, to hear genetic makeup talked about in terms I am more familiar with relating to intellectual property. (Just as Winnie the Pooh is in the public domain as long as he isn’t wearing his Disney-licensed shirt, do you cease to own yourself when you’re translated into a form that can be printed on the pages of a scientific study?) These inventions may not be new, but A Common Sequence ties them together in a neat web of synthetic horrors, posing unanswerable questions—what’s an apple to a machine that cannot eat?

A Common Sequence screens this afternoon, March 18, at the Museum of the Moving Image as part of First Look 2023 and “Science on Screen,” the film’s New York premiere. Directors Mary Helena Clark and Mike Gibisser will be in attendance for a Q&A.