The five films screening as part of Metrograph’s mini retrospective, “The People’s History: Early Films of John Sayles,” place complex characters within vivid sociopolitical contexts that mold their material existence as well as their interpersonal relationships. The films span the late ‘80s/early ‘90s independent film boom that Sayles himself foreran with his self-financed debut, Return of the Secaucus Seven (1980). In Metrograph’s series, coal miners (Matewan, 1987), professional baseball players (Eight Men Out, 1988), failsons of property developers (City of Hope, 1991), Irish fisherman (The Secret of Roan Inish, 1994), and South Texas sheriffs (Lone Star, 1996) struggle against the past, the elements, and the dollar in order to eke out a dignified existence.

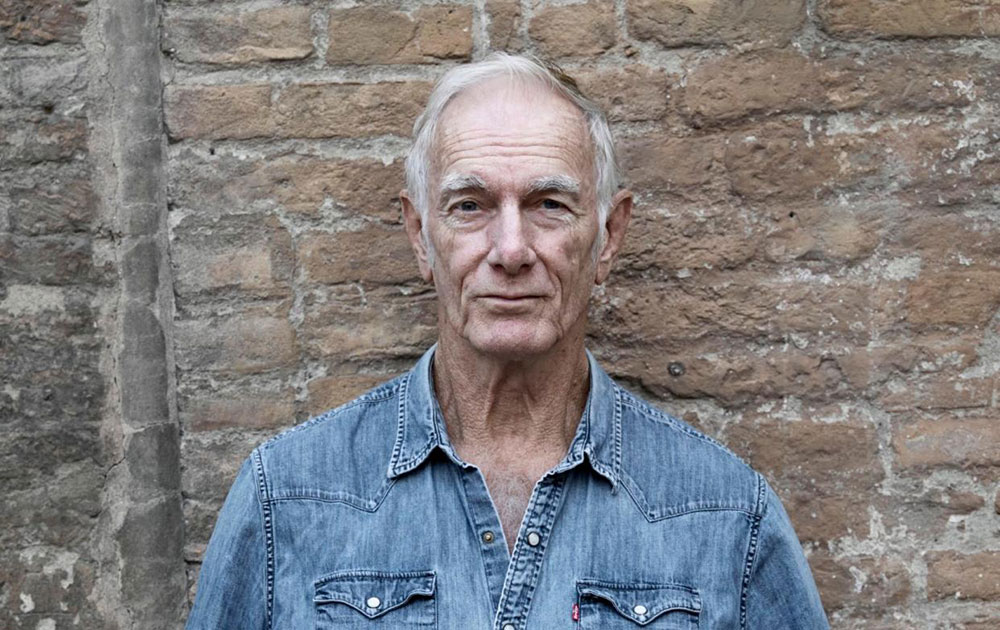

On the occasion of “The People’s History,” I spoke with Sayles about his approach to filmmaking, as well as the desperate state of the movie business. Our conversation has been edited for clarity.

Patrick Dahl: When I look at this group of films, I’m struck by how vivid and diverse the settings are: Appalachia, 1990s urban America, interwar Chicago, the Southern Border, and an Irish fishing village. Is there a consistent moment in the process where setting becomes crucial?

John Sayles: It’s often pretty much Intrinsic to the story itself. You know, this particular thing would happen in this time and place. With Sunshine State [2002], I had written a short story, but when I went to the west coast of Florida, I realized it had changed so much since I had been there as a kid. The story had been about treasure hunters, but after visiting I decided to make a film about the change from mom-and-pop tourism to corporate tourism.

PD: That nullifies my next question, which was going to be: “Have you ever had to change the setting of a movie?” It sounds like you’ve had the opposite happen more often.

JS: I have had to change where I was going to shoot it. A couple of my movies are set in an unnamed Latin American country. Men with Guns [1997] was the first one. It probably should have been shot in Guatemala or El Salvador, but they weren’t safe places to work then for either me or for the people who work with us there. We ended up shooting in Mexico, which was fine.

Right now it looks like we’re going to get to make a movie, a Western, that we had tried to shoot in New Mexico. But then, President Trump closed the government down. A lot of our locations were on government land and our money fell apart. Now, it looks like we may have the money to shoot it in Spain on the old Sergio Leone sets. As far as the movie is concerned, it’s going to be the American West of 1898. As far as we’re concerned, it’s the third place that we’ve tried to make it.

PD: As I was preparing for this interview, I realized that Go For Sisters, released in 2013, was your most recent film. I know you’ve written several novels since then, but I was prepared to ask you if you considered yourself retired from directing. I’m happy to hear that’s not the case.

JS: Not retired. I had been retired, and left to stand in line. Half of the filmmakers I know are still trying to get their next movie made after years and years and years. It’s a really hard thing to get to do, especially if you’re going to work with professionals. I couldn’t even get a two-and-a-half million dollar movie off the ground. Two of those novels were based on screenplays. We finally felt, we’re never going to make this. We’ll never raise that amount of money. So I made them into novels and expanded them. But, they’re not novelizations.

PD: How conscious are you of budgetary restraints when you're in the writing process?

JS: It depends on who I’m working for. I’ve written things for James Cameron and Steven Spielberg. With them, the sky’s the limit. I’ve written things and thought, I don’t know how they’re going to do this, but if they want to do it, they’ll invent it. When I’m writing for myself, I’m very, very aware.

I’ve made enough movies now that I can ask myself: How much night shooting would this require? Do I have a character who’s just sitting there and I’ll have to pay him as a weekly player even if he only works two days? Can I combine his line with another character’s lines so we don’t have to hire two actors? It’s not cheap. I’m constantly editing as I’m writing. I’m also going to be the editor of the movie, so I’m editing as I’m shooting. I’m always mentally saying, I’ve got that, I’ve got that, We’re done with the scene.

PD: Is all of this planning in diagrams or lists, or just in your head?

JS: I have a shot list in my head when I come in for the day. I have a plan of attack for every day, every sequence, and every scene. What I’m doing is emotionally checking things off. That actor really nailed that moment. Somebody blew a line, but I’ve got that covered in another take. I’m editing in my head, so I already know what I’ve got when I go into the editing room.

PD: Because you’re writer/director/editor, the films are very much your vision. You’ve worked with brilliant cinematographers and brilliant actors consistently, but, not to shortchange anyone else, they’re ultimately serving your vision. How do you approach organizing everyone’s work?

JS: I don’t do much rehearsal. What I do with the Director of Photography is go around the sets. I’ll have drawn them some pictures of what’s going to happen. We’ll go there with the production designer so that if the room isn’t built or dressed yet, we’ll talk about what it will look like and I’ll say, “This is what I want. You tell me what time of day I should shoot this.” They have a lot of input in the scheduling. I’ll talk to them about style, usually by giving them an emotional thing. Scene 32, I want this to be tense. I don’t have a technical vocabulary for this stuff, but we find out what combination of variables—lenses, focus, distance—gets us what we want and doesn’t get us into trouble. I know enough technically to know what I can hand over to the people who have skills that I don’t.

PD: How about the actors? You said that you don't do much rehearsal, so are you blocking everything while shooting?

JS: After they’ve been cast, I’ll talk to the actors on the phone, or in person if we’re lucky, enough to be on the same coast. I’ll send them a biography of the character. Even if you have a half-page scene, you’ll get a biography of all the things that I’d want to know about the character if I were an actor. A couple times, I’ve written a little short story from the point-of-view of that character. All I say to actors when they come to the set is, “Know your lines and who you are.”

I like the shock of the new. I’m going to throw actors into the ring with one person, two people, three people. The first take will be the first time you’ve heard these things pitched at your character and you’re going to react to that instead of your memory. I prefer to have people go in knowing what they want and who they are, and then bumping into the other characters in the situation. Sometimes we’ll do blocking rehearsals, but I’ll say, “Say your lines several times outright, but no acting.” I try to make it so they don’t have to look down at tape marks or feel a sandbag at their feet, which are distractions. I might say. “After she says this line, you’re pissed and you’re going to go grab a bottle of wine, but you don’t know exactly where it is.” And I’ll put the bottle in different places on set so that they don’t have to pretend to look for it. It’s not going to be hidden, but they’re not going to know exactly where to get it.

PD: Speaking of acting, you consistently acted in your own films until 1992, but not since.

JS: No, I was in Honeydripper [2007]. And I’ve acted in other people’s movies. The people who [direct themselves] regularly tend to be people who have a persona. Charlie Chaplin, or even Clint Eastwood. He has a couple personas, but they’re pretty close to each other. They’re not thinking, Who am I?, when they’re going back-and-forth between the different sides of the camera. I usually try to play a character who has no arc. In City of Hope, I play this guy, Carl, who’s an asshole. But, he’s exactly the same asshole at the end of the movie. Even though it’s a pretty big part, I didn’t have to think about what he learned or how he’s changed by the end.

PD: A lot of the films in the Metrograph series are period pieces, or have sequences that are period. What does historical research look like for you?

JS: I’ve done quite a bit of research for my novels, as well as my movies. Who you are depends on a lot of things. Although there have been a lot of successful movies where… Let's have it be set in Regency England, but we’re gonna have a cast of all races and people are going to talk in contemporary jargon… That is what it is, but it’s not what I’m trying to do. I’m trying to determine: What did these people know? What were their thought patterns? What was the view of the world they had? Are they in the mainstream of that point of view? Or are they somebody who’s on the outside of it? What were their attitudes likely to be? Was this before Freud? Was this before the women’s movements? Was this before capitalism? Those answers change things quite a bit. Your research addresses how things went down back then. What about technology? If people were shooting guns at each other, is it black powder? Smokeless rifles in the Philippine-American War meant you didn’t give your position away by firing, so the fighting itself changed. The choice to fire or not changed. You discover things as you’re doing research that are really cool and give you better ideas. Or, you discover that you have a character who’s acting in a way that nobody would have acted back then.

PD: Is there a film of yours that you wish would circulate more or have a resurgence?

JS: I would say most of them. Not enough people saw Limbo [1999]. Amigo [2010] didn’t get much of a run. The movie that we probably got the best reviews for ever was City of Hope, but they all used the word “grim” in the opening line. Not that many people said, “Honey, let’s go see something grim tonight.” Our last several films didn’t even have a distributor. We had to find distributors who we paid to put the films out there. That’s how tight it’s gotten with exhibition.

“The People’s History: Early Films of John Sayles” continues through Sunady, April 27 at Metrograph.