In one of the most famous trans allegories in cinema history, The Matrix (1999), directed by the Wachowski sisters, the main character Neo is offered a choice: take the red pill and experience awareness—the awful truth of the world made manifest. Or take the blue pill, and return to the ease of illusion.

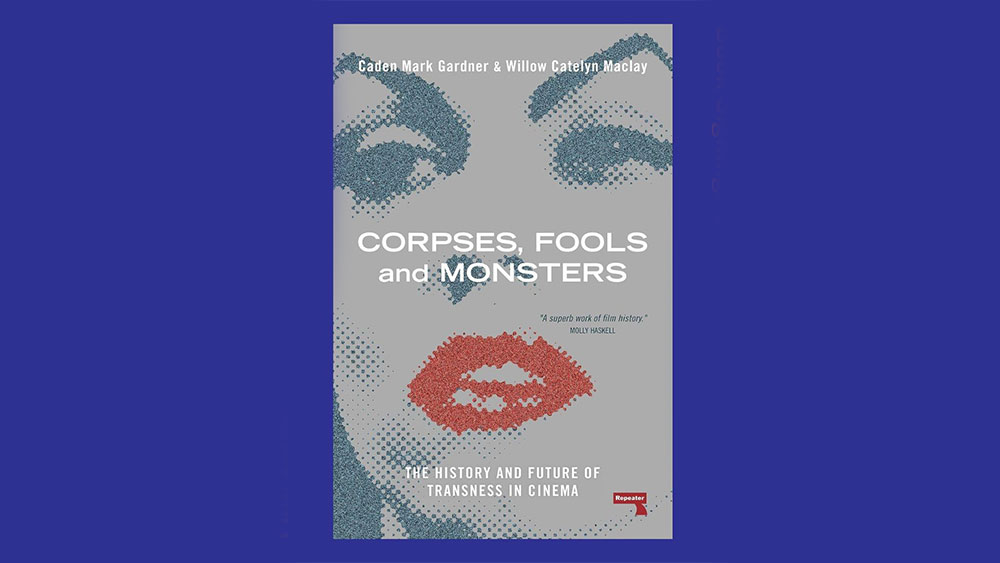

It’s an image so repeated as to be cliché, rehashed and recontextualized so ubiquitously that it arrived to me for the first time in the form of a meme. At risk, then, of repeating a cliché: the critics Caden Mark Gardner and Willow Catelyn Maclay have constructed an equally revelatory pill in the form of their new book, Corpses, Fools, and Monsters: An Examination of Trans Film Images in Cinema, which launches this week in tandem with a screening series called From the Margins, July 13-20 at the Museum of the Moving Image.

Over eleven extensively researched, passionately argued chapters, they detail the history of the trans film image in mainstream cinema, tracing a complex body of work that goes well beyond the reductive tropes of “corpse,” “fool,” and “monster.” In highlighting film images that alternately subvert and reinforce those archetypes—correspondingly complicating and maligning their offscreen counterparts—Gardner and Maclay chart a path to a new frontier for trans cinema, one in which its subjects are no longer forced to negotiate the grounds for their very existence. By the end, I was looking at the world with new eyes, returning to the films of my childhood in search of trans film images at the margins. Blue pill be damned; especially now, we all ought to see.

Leah Abrams: You both have independent careers as critics and you live in different physical locations. Yet your book reads so seamlessly as a coherent project. How did you achieve that on a process level?

Willow Catelyn Maclay: Caden and I did frequent Zoom meetings to discuss the book. I think we were talking like once a week or something. So we figured out: Okay, Caden's going to write about this film or this topic, and I'm going to write about this film or this topic. After we were done with the draft, we would come back and meet each other in the middle and edit one another, and make it sound like one voice. The most crucial thing is that we had really good communication with one another.

Caden Mark Gardner: It’s one of those things where it's a departure from our Body Talk series, which is an actual, conscious dialogue.

But I definitely think it helped that we’d known each other for so long and had been having these conversations for so long, both as critics and as friends. We weren't just strangers plucked from different parts of the world and told, “Well, you're a trans man and you're a trans woman. You can clearly make this work.”

LA: The book gives a historical account of the trans film image, almost in chronological order. How did you decide to structure it that way?

CMG: I think we always wanted to position Christine Jorgensen as the first significant trans film image—that kind of changes everything. A lot of queer storytelling comes from this pre-stonewall, post-stonewall mindset. But I think we both always had the intention of positioning Christine Jorgensen as that figure. Because the tropes that eventually become prominent within trans storytelling come to light after the American public learns of Christine Jorgensen.

There was this sort of exoticism surrounding Jorgensen, going to another country and changing to a whole different sex. People were like: “Oh, she was an American GI. What happened? What are we going to do with this person?”

It also denotes how—in American society, at least—there wasn't really this progression that we aspire toward when it comes to the possibilities of trans visibility. Instead, we see these cycles of activity that happen. Visibility, then backlash. And I think in terms of doing the historical progression, I thought it was important.

WCM: We also wanted to present it chronologically because, one thing we want the reader to come away from the book with is that the trans film image—or the concept of “trans cinema” as a whole, if you want to call it that—is something that has been in a constant negotiation with itself. It grows and then fades and then grows and then fades. All the while, it's struggling to be born through this entire process… to the point where even films that are more modern are in communication with the films from 30, 40, 50 years ago, because we've been stuck in this kind of starting gate feeling.

LA: You quote the Susan Stryker film [Christine in the Cutting Room, 2012] in that early Jorgensen section—and it brings up this distinction between the private image and the public image. And I wonder whether that fracture or disruption is central to the trans film image and how it’s created

CMG: It's not particularly novel to say: I respect the hell out of Susan Stryker. We owe so much of this book to her. It can't be understated.

But yeah, it did make me think back to that post-World War II period where, with so much change, there were so many possibilities. Even in the case of Jorgensen, we cite old newspaper clippings of her coming out, and there was an initial kind of positivity. Like, look at what we can be capable of as humans. But then people got nervous. And we continue to see that reverberate today. This might sound crazy, but the reason why we're years behind in trans healthcare is the same reason why we don't have universal healthcare, or a bullet train system. We could do it. We have the resources… But these conservative, parochial power structures prevent it. And trans people don’t ask for this debate. We don’t want our bodies to be sites of political discourse or tabloids.

LA: That brings us pretty naturally to the framing concept of the book. You start with this idea that mainstream depictions of trans characters are confined to “a lost highway of corpses, fools, and monsters.” I would love to talk a little bit more about how this concept came to you and how these three tropes set up a grounding principle for the book that you write both into and against.

WCM: I think it was born just from our own cinephilia and our own anecdotal experiences of growing up when we did. Caden and I are both children of the nineties. So this is right when Silence of the Lambs [1991] hits. So there’s your monster. It's right when Ace Ventura [1994] hits, so there's your fool. As for the corpses, you saw all these television shows, procedurals like Law and Order and CSI, where every now and then there was an episode investigating a murdered trans sex worker or something. Then you have Boys Don’t Cry in 1999, which is the ultimate trans martyr film.

So these tropes were very obvious to us because they were just in the air when we were growing up. I don't even think it was something we decided to pinpoint from the very outset, it just emerged because these tropes are so common and so dominant within trans film images in the mainstream. We wanted to take these tropes and—not so much reclaim then—but just shed light on the fact that this is how the world sees us.

I think it's important to stress too, that these are prevalent up until very recently. The Danish Girl came out in 2015, less than ten years ago. The Hangover had a trans panic joke just fifteen years ago.These things were still percolating when Caden and I were coming out of the closet, and even when we were becoming film critics in 2014, ‘15, ‘16.

CMG: I think it was The Hangover Part II [2011].

WCM: That’s right. But we prefer to forget The Hangover franchise.

LA: I think we can all agree there. Your analysis is able to both point out the places where those tropes are subverted in film, and other places where the tropes themselves are endowed with their own almost liberatory power. I’m specifically thinking of your discussion of Ginger Snaps [2000], where the main character’s monstrous transformation is read as a parallel for the dysphoria of puberty. How did you find this line with each work?

WCM: I think intent matters a lot. If the director is coming from an empathetic place when considering the monster character—which we can date all the way back to James Whale’s Frankenstein [1931]—it changes everything. Frankenstein is a great model for this sort of trans empathy toward monstrous characters in horror. You mention Ginger Snaps. The way that film functions is that it depicts the horror of puberty and menstruation for cisgender teenage girls, and how it fucking sucks a lot of the time. I think that the film empathizes to such a degree that they incidentally ran into this experience that rings true for trans feminine people in their own puberty. The main character is experiencing changes in her body that she doesn’t want. She transforms. I like to say that any character who undergoes a transformation is a trans character. And that film is a great example.

CMG: Just to go off of what Willow already said, I remember going to the Toronto Film Festival screening of Under the Skin [2013]. I was closeted at the time. I remember Jonathan Glazer introducing the film and you could tell that he was bracing himself for a very polarized response. So he gave this qualifier, like: “Try to imagine Scarlett Johansson's character as a prism observing humanity.” And when I watched it, it just hit me on a deeper level—this person who is observing human behavior—but then she starts embracing and enjoying the embodiment of womanhood. We see her recognize something true about herself in the performance.

It's not intentional by Glazer. I don't think he had trans people in mind at all when making the movie. But still, it hit me very powerfully when I watched it. And I found that experience of projecting my anxieties onto that image so moving.

Then, on the flip side, Dressed to Kill [1980]. I don't expect Brian De Palma's work to always be in good taste. In fact, I usually expect it to be in bad taste—and some of that can be very enjoyable as far as popcorn entertainment. But finding yourself, as a trans person, reduced back to the Psycho [1960] trope in his work… I do wish that when certain directors just insert trans people into their narratives that they would be careful. And I'm not saying, “Oh, they have to follow the GLAAD media guide version of it,” but more like: “What purpose is this character serving? Are they just a plot device?”

LA: The book is accompanied by an upcoming series at the Museum of the Moving Image, From the Margins: The Trans Film Image. Why did it feel important to have a companion series with the book? And how was it to narrow it down to these five films? I do not envy that task.

WCM: I think we always wanted to have films playing alongside the book. We worked with Michael Koresky from MoMI, who’s been really supportive of the book, to create this launch… And, it was a long process of trying to narrow down which films would be a very concise portrait of what the book offers.

We have a wide ranging selection. Some are more populist than others, but we're passionate about all of these films and they all tie to a different aspect of what we were going for in this book. I would just like to add one thing about Ma Vie en Rose [1997]. That was one of the films we definitely wanted to include for political reasons, because we're both so heartbroken by what's going on with trans kids in the United States in particular. We wanted to stress that film in the series because we wanted to underline how transness does manifest within children. They know what they're talking about. And we have to listen to them when they speak and describe how they feel.

CMG: We do point out in the book how devastating it is to know that, in the United States, that film is rated R—which is bizarre! There's nothing objectionable in that movie. So often just being a trans person on a social media app or just… existing… is considered “adult,” “inappropriate content.” Just imagine a sweet movie like that, where the kid has these imaginations about their doll in these magical realist, alternative worlds. This can be a very conservative country in so many ways.

LA: The name for the series with MoMI is From the Margins. I wondered about that choice and how you came to it.

WCM: I think it was born in our initial idea of the trans film image itself. Caden and I are both skeptical that “transgender cinema” even exists. We both kind of believe that it's more truthful to say that images of transness end up in films, in fragments historically. So we took this idea of “from the margins” to say that transness is literally in the margins of film history.

LA: I found the end of the book very hopeful. You start to lay out this future, the new frontier. When you survey that landscape, who are the trans artists that are giving you hope and making you excited about the future?

WCM: In the book, we highlight Jane Schoenbrun. We look at Alice Maio Mackay, who I think is 20 now? But she already has a handful of features under her belt. We’re excited about what she brings to the table because she's working in a mode that is less burdened by the past and kind of liberated toward her own mindset—of having grown up with access to images of trans people.

These younger directors, they've grown up around social media. They've always had access to trans people, not just in TV and film but as full people. And that shows up in her work—it’s more unfiltered from the tropes and the baggage of the past.

CMG: I also want to highlight Henry Hanson, whose short Bros Before [2022] is very fun. It's definitely made by someone who basically made it just for their friends, and it’s full of these easter eggs that only trans men could ever possibly understand. It just felt like a different energy from what I often see in portrayals of trans men, which can sometimes be condescending. But at the same time, it’s also only a fraction of the sort of bullshit that trans women see in media depictions around them.

WCM: The most beautiful thing about the final chapter of our book is that there are now films and directors that Caden and I regret we didn't have time to include. Films like I Saw The TV Glow [2024] and Stress Positions [2024] that came out after we filed. That’s something we never could have predicted when we started this book in 2018.

“From the Margins: The Trans Film Image” runs July 13-20 at the Museum of the Moving Image.