A year before Melvin Van Peebles’s boundary-pushing Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song (1971) earned an X-rating from “an all white jury,” Ossie Davis made the Blaxploitation ur-text with his big-screen adaptation of Chester Himes’s novel Cotton Comes to Harlem. Where Van Peebles and many of his contemporaries found popular appeal and box office success for their unapologetically raw style of filmmaking, which was made possible by the relinquishing of the Production Code the previous decade, Davis’s film appropriated ‘60s pop art and made it a part of its mise-en-scène to depict Harlem at the turn of the ‘70s.

The energetic Manhattan neighborhood at the heart of Davis’s film has very little in common with other, decidedly grittier, films shot in the city by Davis’s white contemporaries that same year. Films like Hal Ashby’s The Landlord, Brian De Palma’s Hi Mom!, and Paul Morrissey’s Trash all revel in an urban squalor that Cotton Comes to Harlem doesn’t reject, but instead relegates to the sidelines in order to focus on a vibrant version of Harlem that’s awash in color and has more in common with Gene Saks’s freewheeling comedy Barefoot In the Park (1967) than any other film. Cotton Comes to Harlem was the only feature film directed by a Black filmmaker in New York City that year, paving the way for Gordon Parks to helm Shaft the following year, as well as Van Peebles’s release of Sweet Sweetback.

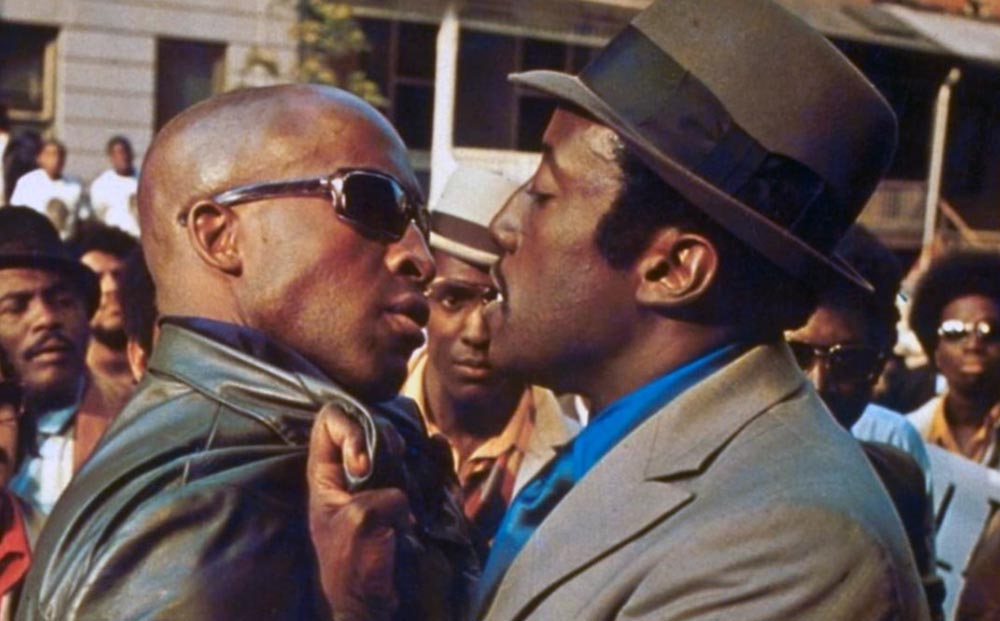

Davis’s depiction of the city in vibrant hues isn’t the only thing that sets his film apart from the gutter cinema of his NYC-peers or his Blaxploitation contemporaries. Cotton Comes to Harlem, even more so than the Himes’s novel it's based on, has a narrative logic that’s closer to that of a comic book than real-life. The heroes of the film are two NYPD detectives named Coffin Ed (Raymond St. Jacques) and Gravedigger (Godfrey Cambridge), both on the trail of a nefarious Reverend who is scamming the Black residents of Harlem into buying parcels of land in Africa while pocketing the money. The scammer’s subsequent attempt to smuggle the money out of Harlem in a bale of cotton fails when the bale goes missing. If the plot sounds cartoonish, it’s because it is.

Davis never tries to obfuscate the inherent inanity of Himes’s premise or his larger-than-life characters. Coffin Ed and Gravedigger, despite being members of the police force, are rendered as superheroes. The duo, not far removed from the Batman and Robin of Gordon Parks’s The Super Cops (1974), are portrayed as virtuous, albeit hardened, crime enforcers that aren’t afraid of violence. There’s a pervasive air of invincibility whenever Coffin Ed and Gravedigger are on-screen; they’re unafraid to cross paths with corrupt city officials or the titans of organized crime, always managing to walk away unscathed with their noble reputations intact.

Cotton Comes to Harlem is also a time capsule of early ‘70s Harlem that is as much a celebration of the city and its people as it is a standard historical document; if Sweet Sweetback was a call-to-action, Davis’s film has always been a call for unity. Davis, like his film, feels at home in Harlem, whereas Van Peebles, especially in his role as Sweet Sweetback, is in constant struggle with the city of Los Angeles. Though both films portray systemic corruption in their respective cities, Davis criticizes the system from the inside by framing his film from the perspective of two detectives, whereas Van Peebles’s film is one of the great anti-establishment films because it shows institutions being torn down from the outside by the people it has failed. Cotton Comes to Harlem isn’t often cited as being the progenitor of Blaxploitation in the way that Sweet Sweetback is, arguably due to its lack of incendiary politics, yet Davis’s film and its very existence is inherently political. In an era, and city, rife with genre narratives told from white perspectives, Cotton Comes to Harlem offers a vibrant counterpoint; it is a crime story that is as interested in its own sense of real time-and-place as it is in offering something decidedly disconnected from everyday life.

Cotton Comes to Harlem screens this evening, August 21, at Film Forum on 35mm as part of the series “BLAXPLOITATION, BABY!”