In 1968, on the cusp of the Hays Code being abandoned for a new ratings system in Hollywood, the Italian film producer Dino De Laurentis joined forces with Paramount Pictures to adapt two European comic series for cinema: the French series Barbarella, adapted into a film of the same name by Roger Vadim, and the Italian series Diabolik, adapted into the a film titled Danger: Diabolik by Mario Bava. Though they were released domestically before the new ratings system went into place, the films pushed the limits of onscreen sexuality and nudity, even if tame enough to garner ratings of just PG (for Barbarella) and PG-13 (for Danger: Diabolik) when submitted for certification years later. Beyond being decidedly horny Euro comic adaptations with psychedelia to spare, both films also utilized the actor John Phillip Law as well as the writers Brian Dugas and Tudor Gates. The result is two films that honestly may work better together than they do separated, which Paramount used to their advantage in double-feature bookings during theatrical release. Even taken on its own, Danger: Diabolik exists as the platonic ideal of where comic-book cinema could have gone in decades to come, yet did not.

Paramount, likely correct in assuming that most Americans were not familiar with the source material, had a difficult time marketing Danger: Diabolik. Director Mario Bava’s biggest release in the U.S. at that point was the vibrant sci-fi programmer Planet of the Vampires (1965), and he was undoubtedly on the radar of any self-respecting horror fan, but hardly a name to be touted on many a marquee in the States. Instead, Dino De Laurentis received top billing on the theatrical one-sheets adorned with a colorful pop-art collage featuring, amongst other sights, multiple guns and a nude woman covering her chest with wads of cash. The result looks like an Italian riff on a James Bond advertisement but instead of promising the more genteel thrills of Ian Flemming’s source, it lives up to the tagline which promises the titular Diabolik character to be “Slick. Suave. Gentle. Brutal.”, all adjectives which could also be applied to Bava’s film.

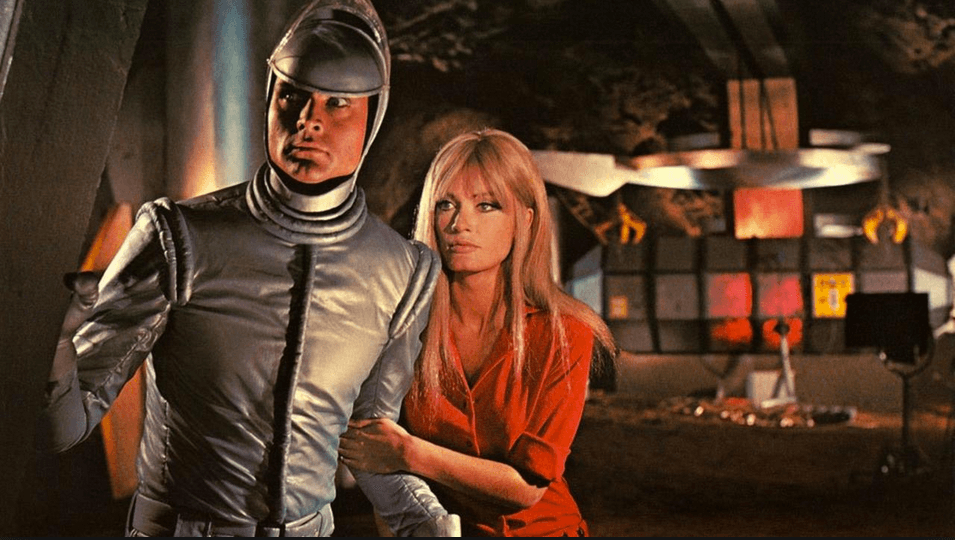

The plot of Bava’s film, not unlike its comic source, is almost comfortably inconsequential—basically a series of conflicts strung together with the cohering trait being that Diabolik is a character that can do whatever he wants, wherever he wants. It’s an anti-hero assault on polite society that fully embraces the candy-colored palettes and loose morals of the late-’60s status quo, with Diabolik just ripping people (mostly gangsters) off and getting away with it, naturally with the aid of an attractive young woman at his side. Plot, or lack thereof, notwithstanding, Bava gets firmly to the root of the appeal of its comic-book source: the visual motifs. With its most obvious peer, at the time, being Adam West’s Batman TV series (1966–68), Danger: Diabolik engages with the energy of comic panels in ways that contemporary Marvel and DC film adaptations dare not. It is simultaneously reverential of the aesthetic and ethos of the comic strip while attempting to render it cinematic, something arguably only accomplished in recent years with Ang Lee’s virtuosic Hulk (2003). Like Vadim’s Barbarella, with which it shares DNA and a healthy dose of spirit, Bava’s comic-book adaptation sets the stage for where cinematic adaptations of such sources could have gone had filmmakers and studios embraced the more inherently artistic aspects of the medium. Rather than feeling like an urtext of what now passes for a superhero movie, Danger: Diabolik exists more as a reminder of how good things could be, the exceedingly rare superhero (or supervillain) film that embraces style over substance and is all the better for it.

Danger: Diabolik screens this evening, December 27, at the Museum of Modern Art as part of their Ennio Moriccone retrospective.