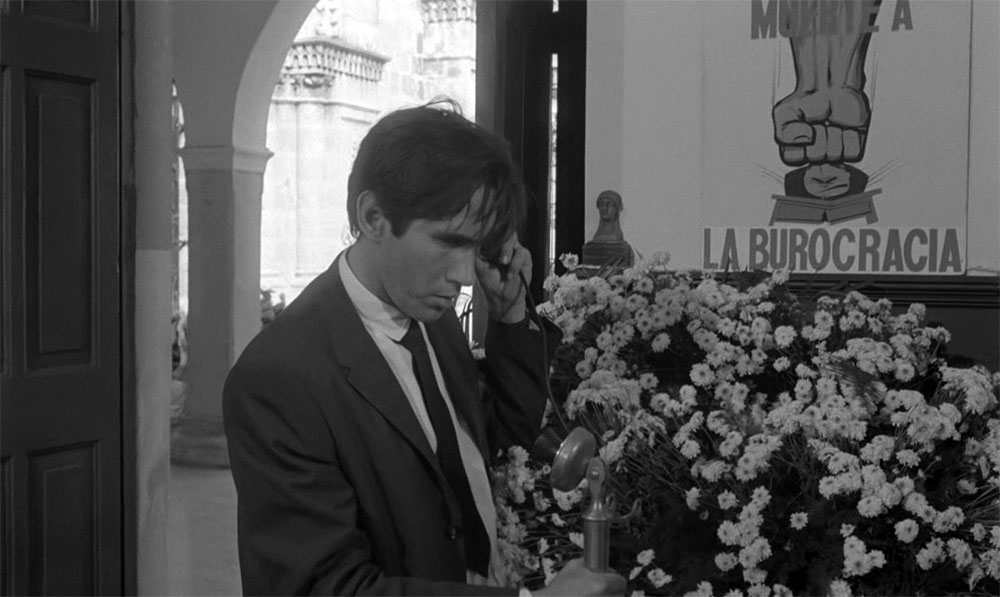

Of course the highpoint of Tomás Gutiérrez Alea’s classic Cuban comedy, Death of a Bureaucrat (1966), revolves around a funny bit of cinematic dialectical synthesis. When a nephew’s (Salvador Wood) umpteenth attempt to have his uncle’s corpse reburied is thwarted, a fight breaks out between the funeral procession and cemetery management. What begins as a somewhat measured exchange of insults quickly turns into a brawl where funeral wreaths are lobbed as if they were pies in a Laurel & Hardy film. Eventually, creamy desserts are also added to the arsenal, making the film’s morbid homage even more apparent. The result is a combination of silent-era slapstick mayhem with the satirical wit of a Buñuel film and the melancholy of a Bergman film.

Death of a Bureaucrat is about a man who is buried with his labor card. In order for the man’s widow to receive the benefits she’s entitled to, she must present the card to the proper authorities. This leads her nephew on a wild adventure through government red tape in order to get it back. But the complications don’t end there. Once the card is retrieved, the body must be reburied. At every turn, another maddening bureaucratic complication thwarts the nephew’s best efforts. As absurd as things get though, there is a perverse and thorough consistency to the paradox Gutiérrez presents where you can’t exhume a body until it’s been buried for two years, so if you dig it up illegally you can’t have it reburied without a document proving it’s been legally exhumed. All the while, buzzards begin to circle the corpse.

During the film’s opening credits, the viewer gets a heavy hint regarding Alea’s freewheeling cinematic influences; the scrolling list of acknowledgements includes everyone from Ingmar Bergman to Stan Laurel, from Akira Kurosawa to Marilyn Monroe. This wide swathe of names could ostensibly precede most films, but in Alea’s communist fable they are synthesized into something wholly original. Featuring an animated collage, surrealistic dream sequences, and slapstick, The Death of a Bureaucrat exuberantly employs a variety of cinematic modes to create a work that’s fun, anxiety-inducing, and pointedly critical of Cuban bureaucracy—so much so, that Gutiérrez was allegedly forced to smuggle the film out of the country for its release in the United States. His film is a key work of the New Latin American Cinema, or “Third Cinema,” of the ‘60s and ‘70s. Its playful dance of cinematic influences are clearly meant to delight, but they also work to deconstruct the passivity of the viewer. To watch Gutiérrez’s film is to watch a history of cinema, a material history being activated in a work that does not seek to mask itself through a verisimilitudinous magic trick, but instead invites its audience into its act of creation.

Death of a Bureaucrat screens tomorrow afternoon, April 13, at The Quad as part of “Laughing through Rebellion: The Cine Libre of Tomás Gutiérrez Alea.”