On March 12, 2020, or “Black Thursday” as it came to be known, global stock markets plunged, Major League Baseball canceled spring training, and Tom Hanks announced that he and Rita Wilson had contracted Covid-19 while in Australia filming Elvis. The pandemic was swiftly becoming real to the New York City public, and I was to be sent home from work early the next day, never to return to my basement cubicle at the New York City Ballet. But at 9:30 p.m., I was at a sold-out screening of Surf Nazis Must Die (1987) on 35mm, crammed alarmingly close to my fellow “Deuce” denizens in the big house at Nitehawk Williamsburg.

Launched in November 2012, “The Deuce,” a monthly, 35mm-only series celebrating the 12 theaters on 42nd Street between 7th and 8th Avenues and the grindhouse fare they pumped out daily in the 1970s and ‘80s, has become a cherished ritual to many of the hundred people that show up each month, and as such naturally provides a soothing mnemonic device for a catastrophic moment like the shutdown of the city. The format for a night at “The Deuce” hasn’t changed: each begins with a pre-show of trailers and media related to the feature film and the theater on the Forty-Deuce where it premiered; an introduction by Joseph “Jo Zeig” Berger, followed by a stump-stagger through that theater’s history by “Tour Guide” Andy McCarthy; the film itself, often on a beat-up, dusty, red print, “pro-Joe-jected” by Joe Muto; a raffle set to Hot Butter’s “Popcorn,” whose prizes include memorabilia and a signature homemade poster from “Maestro” Jeff Cashvan; and, finally, an after-party. “The Deuce” is a full-fledged Event, intended to transport the crowd through space and time.

I spoke to the people who make the shows happen, including Andrew Miller, Max Cavanaugh, John Woods, and Cristina Cacioppo, programmer at Nitehawk, on the occasion of tonight’s hundredth “Deuce” screening. They discussed origins and inspirations of the series, from bus tours to bar screening rooms, as well as its ongoing escapades.

Joe Berger (master of ceremonies): I want to just put down on paper my biggest influences on the series: “Queer|Art|Film,” curated by Adam Baran and Ira Sachs, which is a monthly series at IFC that started in 2009. I loved what they did: their format of guest curators every month, showing and telling about the film—not the artist in question, but a fan of the film being like, “This is why this is important, and here’s how it has influenced my work.”

But more importantly, Bradford Nordeen’s “Dirty Looks,” which he started in January 2011. In July 2012, he did a 31-day festival called “On Location,” where every day there was a site-specific screening-place where he showed some sort of queer historical film. And on July 27—this is so insane—he sat all day long in a booth at Shake Shack on 44th and Eighth Avenue, because that was the location of Chelly Wilson’s gay porno theater, the Cameo. You had to set an appointment with him. I walked in, bought a milkshake, and went to the back corner, and on his iPad, he showed me Loads [1985] by Curt McDowell.

For me, it's not really about the films in question. It's the history of how they were shown, where they were shown, to whom they were shown. “On Location” was so exciting because he was literally placing me in a historical location, giving me a time travel experience. And maybe two or three months later, Andrew Miller came to me and was like, “Joe, pitch me an idea for a monthly series.” I remember the day: I was walking around, circling my apartment on Sixth Street and Avenue D, pitching this fully-formed idea to him called “The Deuce.”

Andrew Miller: We met at a time when the NYC repertory scene was in a weird place, sort of calcified around highbrow fare. And if programmers tried to screen anything outside the confines of the canon, they had to do this weird little dance, making sure everyone knew they were just being ironic.

Max Cavanaugh (Nitehawk Technical Director): I was working in the box office at Film Forum, and Andrew and I were just starting to think about a series, just to do something. And we couldn't find a home for it. So we went to Cristina [Cacioppo], and she was like, “Yeah, totally.” Cristina always plays this down, but she really is the big bang of all of it—her philosophy around 92Y Tribeca and the world of people that she cultivated there. From “We Love Bad Movies,” to her programming “Beer Goggles,” to our series “Basic Cable Classics.” I believe that was the first place where Cool as Ice [1991] was shown. Cristina was game for anything.

Cristina Cacioppo (Nitehawk programmer): 92Y Tribeca opened in 2008. When I was hired, I think I was just lucky—a younger programmer who slipped in and managed to get an opportunity. I thought that other cities had this sort of fun, cult programming that New York was lacking. New York had a lot to offer as far as filmgoing, but it didn't really have this edgy kind of thing going on; so that was the gap I was looking to fill. I also wanted collaborators, because I wanted to reach audiences. It was about finding the community out there, and that manifested in the form of co-programmers or guest programmers. Clearly, there were a lot of people looking to do something. I would get people pitching me different kinds of series. “Basic Cable Classics” was one of those, and I was like, “Of course. This is exactly the kind of thing that I'm trying to do.”

Max Cavanaugh: The idea of “Basic Cable Classics” was that Andrew and I were latchkey kids, we both had troubled domestic experiences, and we turned to movies for solace. You go home, you turn on TBS, and it's the same movies every Friday. So I was like, “Let's turn that on its head and watch these films in a new context.” The concept was to elevate the movies, like showing Real Genius [1985] with [director] Martha Coolidge, Just One of the Guys [1985] with [director] Lisa Gottlieb, The Peanut Butter Solution [1985] with the director Michael Rubbo on Skype from Australia.

That's where the whole 35mm thing came from—it was a requirement for Basic Cable Classics. I love it for more than the format. I think if you see something on film, that automatically elevates whatever it is you're showing, especially given the fact that you have artisans like Stephen Coco and Joe Muto making sure that these films are shown properly. Coco is the projectionist at Alamo Yonkers; he was the projectionist at 92Y Tribeca and was game for the 35mm requirement. It was sort of a magical thing that happened, doing 35mm for like, 70 people. It's the kind of thing that you couldn't repeat.

Then, in March 2013, 92nd Street Y announced that “a second, physical location” was not critical to their mission and shuttered the Tribeca theater, cutting short the lives of any number of series and film fests that were now bereft of a venue and a budget. Meanwhile, on November 9, 2012, Videology, the now-shuttered video-rental store in Williamsburg, launched its back screening room and a bar up front, bringing on Miller as a co-programmer with filmmaker Zach Clark.

Andrew Miller: Videology wanted to feel like a party, but by nature it had to be a low-key, chill one—the place only had 40 seats, with upstairs neighbors and a landlord who wasn’t so hot on the idea. It also didn’t have all the bells and whistles I was used to over at 92Y, like PR contacts or a budget that could foot the bill for 35mm, though we managed to wheel in a 8mm projector once or twice. My thinking was that if Videology wanted to be where the party was at, then we should treat it like a party and invite our friends, and maybe they would bring their friends. It wasn’t even a question that Joe had to be involved. He’s a born master of ceremonies; at that point, he’d already been crowned by the Village Voice as #1 super-fan of The Apple [Golan & Globus’s 1980 science-fiction musical].

Joe Berger: The excitement around The Apple was that it was a “lost film,” a 35mm print that had been sitting in a vault since 1980. Landmark Theatres “rediscovered” it and sent it off on a national tour. In 2003, we saw it and lost our minds. We were right on the cusp of losing that experience entirely—we were well into streaming and Netflix—so to have that experience at Landmark Sunshine Cinema [RIP], Memorial Day weekend, that was so thrilling to me. Jake Perlin then challenged me to host The Apple at BAM, and I ended up selling out two of the three shows on a Wednesday in December. It was instantly about my love of playing show-and-tell: present this film, generate the energy, set the tone, and make it a party, something to remember. I became NYC’s Apple superfan, and since 2003, I’ve hosted something like two dozen midnight Apple screenings, all over town.

Andrew Miller: I asked Joe if he wanted to do something at Videology and he suggested an homage to the heyday of 42nd Street grindhouses. I immediately thought of roping in my pal Andy McCarthy, who had Deuce bona fides—he’d done time as a Times Square tour guide, had direct access to an insane library of archival images through his day job, and could quote chapter and verse from books like Josh Alan Friedman’s Tales From Times Square. If anyone was going to make you feel like you’d been beamed back into NYC’s dirtbag heyday, it was Andy.

Andy McCarthy (tour guide extraordinaire): In my twenties, my friends and I always thought we were hilarious goof-offs and everything, but I never thought of pursuing any kind of performance. I was never someone that was into public speaking, and I can't memorize for shit. But I gravitated toward the tour bus because I just needed a job and it seemed like a lot of fun. And the only job requirement was that you had a pulse, basically. I was doing it every day, I could develop it as I went along. It got to the point where I could do each tour at least twice a day and not repeat a single thing. I felt like, I'm one of the hardest working performers in Times Square. I'm an Off-off-off-off-off Broadway performer.

Then I went to library school, and now I'm a librarian at the local history and genealogy division at New York Public Library. The benefits of that are the resources that I have access to, all kinds of stuff that’s ended up informing the spiels I do at “The Deuce.” The stump-staggers are steeped in my tour-bus background—I’m talking about history, but it's a little loosey goosey. We’re givin’ a tour; no one really cares about the facts, especially not the tour guide. Sometimes I just make up slang words that sound like they could be old slang words. It's factual, and it’s a lot of work, but it’s about having fun, dumb jokes, playing on words, and a few cool anecdotes in there, riffing off of whatever movie is going to be playing that night.

Andrew Miller: Joe brought on Jeff as curator, which also seemed like a no-brainer. Jeff was the only one we knew who had frequented those grindhouses in his youth, and to boot, he’s got this preternatural ability to pick just the right movie, often one completely lost to the sands of time, something audiences never knew they wanted to see.

Jeff Cashvan (raffler-in-chief): I used to go to “The Deuce”—I mean, that was often where I would see movies, because it was exciting and there was so much to see. I worked at the Avenue A Kim’s [Video and Music], at the dry cleaners, then I moved over to the original St. Mark's store. After Kim’s closed, a few of us were working at a friend of ours [Michael Mosley’s] video store, Cinema Nolita, that ended up on Mulberry Street. It was a really hard time for video stores, so as a way to try to get people to the store, hanging out, we started doing a movie night there. We would set it up, and people came. It was hilarious. Abel Ferrara came for Ms. 45 [1981], and there's like five people there. We had a connection to Frank Hennlotter, who came and talked for two hours to the five people sitting there after the movie [Basket Case, 1982]. It was quite fun.

When Cinema Nolita closed, my friend Chris [Jacobson] and I started the KGB [Bar] screenings. It's every Sunday night at the Kraine Theater at 11 o'clock. Which is not a great time for a lot of people, but it's what our schedules allow, and it's also why they give us the theater for free. It’s been somewhere between 10 and 15 years.

The whole raffle thing came out of this live show, “Mad Blood,” that we used to do when I lived downtown, on Park Row. I had a strangely large apartment, so I made a set, and we would perform this show for an audience as a horror movie host–type show, then pull down the screen and watch a half hour of the movie, and then do commercial breaks or whatever. Then we would have a raffle.

Joe Berger: We started with Fleshpot on 42nd Street [1972], and the format landed fully evolved, we each brought our own thing to the table.

Jeff Cashvan: The thing about the Videology screenings was that I could kind of show anything I wanted, because we didn't have to get a print. We were just running it from a DVD player or whatever. So Fleshpot on 42nd Street seemed like a good way to start. You got the street right in the title. And Milligan was a local filmmaker, and so connected with that block; he made movies specifically to be there, to be product for that neighborhood. And he’s also one of the most inspiring— for a person to not make a single penny off of something, and continue to do it their entire life, regardless, is an important thing.

Andrew Miller: It was instantly obvious that Videology was an odd fit, if only because paying tribute to the grindhouse era by screening movies on DVD felt like a bit of a sacrilege. There were tech glitches and the tight space didn’t exactly accommodate a show with three co-hosts. But in a way, the scrappy setting was a feature, not a bug; Deuce audiences back in the day went in knowing that something might go awry, and that was absolutely the vibe at Videology.

Max Cavanaugh: [After becoming Technical Director at Nitehawk,] I went to “The Deuce” screenings at Videology a handful of times, and Joe and I were like, “We really have to get this to Nitehawk.” I was trying to convince Matthew [Viragh] that there was a 35mm-only audience that needed to be tapped.

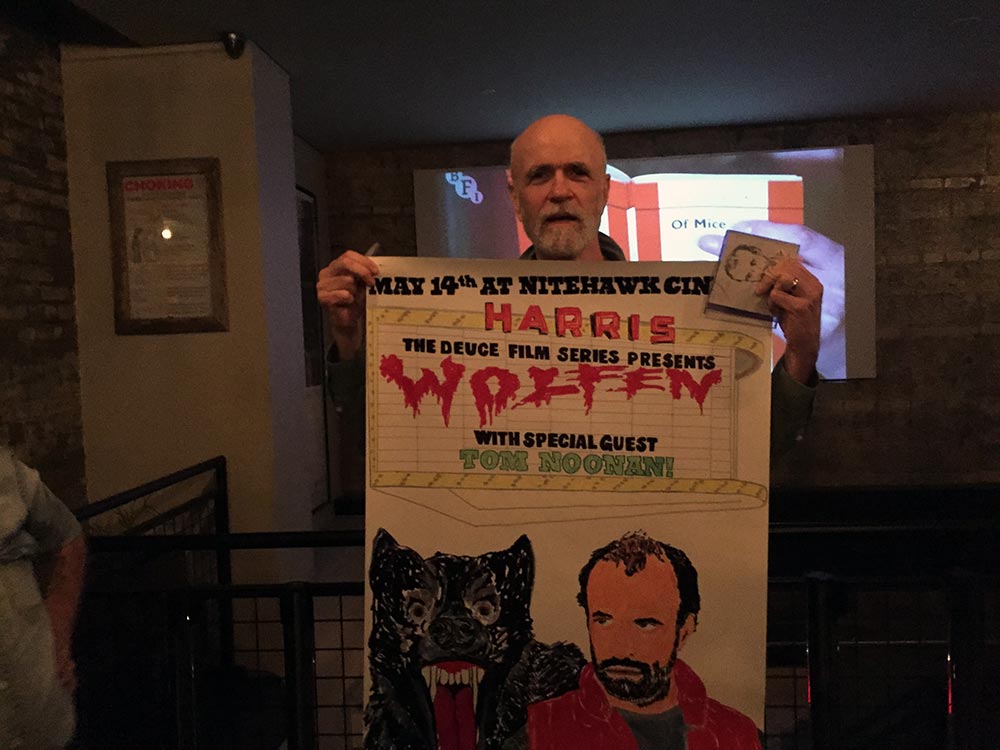

Andrew Miller: I ended up being the point man to rope in special guests, since I had some luck with that for “Basic Cable” and Doomsday. And we scored a good handful: director Gary Sherman showed up for Vice Squad [1982], the inaugural Nitehawk screening; Tom Noonan for Wolfen [1981]; Michael Murphy and Dan Shor for Strange Behavior [1981]. I think Paul Morrissey got spooked by the late showtime (Deuce screenings are basically locked in at 9:30pm), but it was a hoot chatting up one of my heroes.

Joe Berger: We now sell out every show. At the top, I ask, “Who's brand new to ‘The Deuce’?” I would say 60%, 70% of our crowd are die-hard, every-single-month “Deuce” denizens. And then there's a handful of new people that are drawn specifically to the film in question, and they have no goddamn idea what they just walked into, and I usually apologize to them a little: ”Sorry, bear with us. Hang on tight. We'll all get through this soon, I promise. No one will be injured.” No one has been injured as of yet. Jeffie almost.

Joe Muto (Nitehawk projectionist): We do lots of 35mm at Nitehawk, and “The Deuce,” being a monthly series, is really just one small part of that. But the 35mm prints that come in for that series are generally among the more challenging ones to run—challenging in terms of the condition of the print, which can be very scary when you’re not sure whether a film is going to make it through the projector, or if it’ll disintegrate. It's one night only, and I always feel that pressure. But it's a good kind of pressure, because this series has a devoted audience, which is a lot of fun to be a part of—to see that excitement build. Everybody knows what they're there for, and everybody knows what they're in for.

Cristina Cacioppo: It's sort of become a signature thing—we'll call a print “Deuce-y” if it's really faded. But it's the one time that we know the crowd will be into it; nobody complains, because it's kind of part of the show.

Max Cavanaugh: John Woods loves hunting for prints, and Jeff always gave us the best red meat. I remember we showed Dirty Little Billy [1972], starring Michael J. Pollard as Billy the Kid. I absolutely adored that movie, and I'd never seen it. I’d never even heard of it. It’s one of those films where Jeff was like, “We’ve got to show it.” We knew who had the rights, and once it was communicated that we're an archival booth, our contact was like, “Oh, well, then yes, it's here.” After a couple of years, they sent us the print. It was basically an unscreened copy of the film, and it was absolutely, mind-blowingly gorgeous. Particularly considering [that, in] prints from that era [of] the ’70s, everything is usually brown.

John Woods (Nitehawk Director of Programming and Acquisitions): I've had to do this whole Encyclopedia Brown thing for a lot of the screenings. Maybe it's a collector whose collection isn’t really for the public. Sometimes the director will call in a favor with somebody they know that has a print. It's rare these days that we get stumped on something; if it exists, we usually find it.

Jeff Cashvan: People have an idea of what Time Square movies are—you know, Grindhouse [2007], and The Deuce [2019 HBO series], and stuff like that. But something I was always interested in showing with the series was [that] everything played on that street, whether it was an Andy Milligan movie, or Runaway Train [1985], an “Oscar film,” or something nobody would remember. So that's always been the idea. To me, when I was still going, when it was still around, you could liken [the Deuce] to a repertory theater; what you had to choose from there was so vast. In the mid-’80s, I could go see Dawn of the Dead [1978] in a theater, because it was still playing in Times Square.

Cristina Cacioppo: Even when people don't like the movie, it's still an experience, you know? They put so much into the raffle, into Jeff making these prizes and an amazing poster. Even if you watch a movie that's not great, you're still amongst people that are enjoying themselves. I doubt that there's ever been a time where somebody's been like, “I’m never coming to this theater again.” And if they are, they were just never meant to be there.

Joe Berger: I don't give context around how the film was made. Like, OK, James Brolin breaking his ankle on the set of Night of the Juggler [1980] is interesting. But I don't personally give a shit. I couldn't care less about how the film was made. What I'm more fascinated by is: What life did it have? Where did it play? How was it distributed? How was it marketed? Was it redistributed eight times under eight different names with eight different poster designs? That, to me, is what we do.

Andy McCarthy: I always had a thing for the Deuce. It stemmed from doing the double-decker bus tours. 42nd Street is this cross section of New York City history, entertainment history, showbiz history, Hollywood history, architecture, crime, real estate; all this subject matter conjoins there. My interest is, how did this one block go from this glitzy heyday to this cesspool by the ’80s? I'm not any kind of theater historian, but I feel like the earlier history gives it a little bit more character; if you just dwelt on the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s, then it would seem a little too indulgent.

Joe Berger: Our crowd is really sophisticated and really does appreciate what we're doing, what we’re showing. It's not a talkback crowd. We don't heckle the movie. Yeah, our intros and outros are a bit ludicrous. But when it comes time to watch the movie, the hundred people in those screenings really do watch the movies.

Joe Berger: Jonathan Demme came in 2016; we showed Cage Heat [1976], his very first film, and the idea was a conversation with me beforehand. I started with his newest, and his final film, Justin Timberlake + the Tennessee Kids [2016], and I moved backward. He hung around for the entire after-party, he met everyone, and it ended up being one of his last interviews and public appearances before his death.

Max Cavanaugh: I'll never forget him walking into the Low Res bar after the screening. It was just such an amazing night. A lot of people in Pleasantville at the Jacob Burns [Film Center], where he was on the board of directors, had told me that he never really wanted to show Caged Heat. I think we just caught him at the right moment, and he was in a really reflexive mood. He was just such a sweetheart, and that print was so red, but I think he understood the whole elevation idea.

Jeff Cashvan: I’m getting ready for the next one, frantically, as usual. Getting the prizes together, the poster. I'm very excited about Hollywood 90028 [1973] because I haven't seen it. I was going through theater dates, looking for other stuff, and it just happened to be playing the same week—I see this title, Hollywood Hillside Strangler, so I'm like, “I have to look that up.” I see that it's the only feature film Christina Hornisher made. And it just got more interesting the more I tried to find out about it. So it's gonna be a great, depressing, “ruin Valentine’s Day for an entire theater full of people” screening.

Joe Muto: This has been a decade-long learning experience for me, too, because I've never heard of or know anything about the films. Once in a while, they throw in something that’s much more popular, and Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan [1982] made it in the mix somehow. I remember being so flippin’ excited. And it looked and sounded so good.

John Woods: I was surprised to find out that it's been going on for so long, even though I've been a part of every single screening they’ve done at Nitehawk. It's time-consuming, but it's ultimately satisfying when you do find something that nobody’s seen or that people didn’t think existed.

Joe Berger: There are dozens of books on my shelf right now about the history of Times Square, the buildings and the political and economic machinations that made those buildings possible. But this is really about experiences human beings had, collectively—whether it was seeing Lauren Bacall in Applause at the Palace Theatre, or getting a handjob in the parking lot across from Port Authority on the southeast corner of Eighth and 42nd. These are collective memories, they don't disappear. They never go away. Everyone can stream these movies. In another ten years, there’ll be half the number of theaters than the dismal number that we have now. Some of these guys who are there every single month? I still don't know their names. And I don't see them at any other movies. They're there for us.

Hollywood 90028 screens tonight, February 9, at Nitehawk Williamsburg on 35mm, the hundredth screening of the series “The Deuce.”