The Mexican-American filmmaker Lourdes Portillo’s The Devil Never Sleeps (1994) begins when she learns that her Uncle Oscar has taken his own life and not died of a heart attack, as she’d been told. His body was discovered at the local sports complex with a bullet wound in his head, a pistol nearby, and sufficient gunpowder on his hands to put a police investigation to rest. “When I dream of home, something always slips away from me, just beneath the surface—faces of my family, old stories, the land, mysteries about to be revealed,” Portillo intones in a voice-over that accompanies the image of a rippling surface of dark indigo blue water. This narration announces the nature of her project: to find those elements that “slip away” and present them on-screen. They include family photos and images of her relatives printed by the Chihuahua and Guaymas press; grainy and ghostly home movies; stories her relatives repeat on camera, as well as the secrets they refuse to address; footage of the places where she first fell in love with film and where her cousins once celebrated Christmas; and, at the core, the mystery of Uncle Oscar’s death.

As The Devil Never Sleeps unfolds, we learn that many of Oscar’s family members believe he was murdered and that the culprit was his second wife, Ofelia, who was 20 years his junior and his girlfriend well before his first wife’s death. The film also reveals that she was a former “carnival queen.” Portillo’s relatives also claim that Oscar had changed his life insurance to make her his sole beneficiary shortly before he died and that she must have hired a hitman to carry out the nefarious deed. She was, after all, from a lower-class background, and had successfully acquired the money, children, nice home, and social status she’d desired from Oscar all along, as Oscar’s sisters declaim. They criticize Ofelia’s over-the-top behavior at the funeral and how she distanced Oscar from them, further insisting that she neglected and abused the children from his earlier marriage.

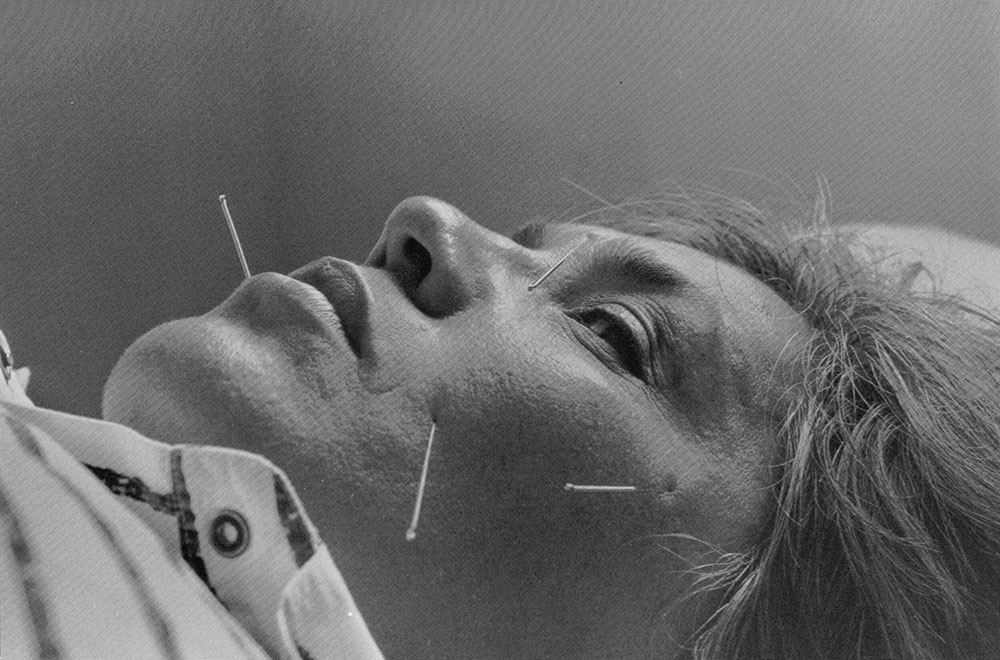

Or was it Pancho Spriu, whose decade-old debt to the dead man was wiped away by Oscar’s untimely end? Or was Oscar’s much commented-upon vibrance and charm merely a mask beneath which roiled the depths of despair? His ranch, one of the first to export vegetables to the United States from Mexico, had contributed to the mortal salinization of the land in the region and he might have been dying of a far-advanced case of cancer, as Ofelia sometimes claimed. A letter found amongst his papers outlined the endless disappointments of his marriage, and how the coins he’d made to commemorate a visit from the Pope weren’t moving. But as his family members insist, what of his projects and plans, his apparent joie de vivre? After all, as his sister tells us of Oscar’s recent behavior, “If you have plastic surgery, then you’re going to take advantage of it.”

When The Devil Never Sleeps was inducted into the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress in 2020, Portillo told KQED that Errol Morris’s The Thin Blue Line (1988) was a source of inspiration. “Morris inspired me to be much more experimental and much more who I was,” she said. “I thought it was good to expand the idea of the investigator, not to be this perfect person who knows all.” His documentary famously combined the narrations of witnesses, police officers, and the accused with the materials that arose from its central case and reenactments to present the many possible variations of what had happened on a fateful night in Texas, thereby allowing the truth to appear to emerge of its own volition and without making any claims regarding Morris’s own knowledge or abilities as an investigator. Portillo similarly relies on visual evidence for each of the potential explanations behind her uncle’s death, though her presence on-screen and as the film’s narrator indicate she is after something different.

In her essay, “Truth, History, and the New Documentary,” the film scholar Linda Williams writes that “truth” is revealed in documentary when a recorded reality of the past is repeated in the re-presentation within the film, using The Thin Blue Line and Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah (1985) as successful examples of this. “In these privileged moments of verite…. the past repeats. We thus see the power of the past not simply by dramatizing it, or reenacting it, or talking about it obsessively….but finally by finding its traces, in repetitions and resistances, in the present.”

How does the “truth” erupt in Portillo’s documentary, which, unlike The Thin Blue Line, concludes as embroiled within its own mystery as ever, floating on a beautiful surface that refuses to give up the secrets below? The answer might lie in its humor: Portillo’s wry comments after phone calls with Ofelia; the juxtaposition of contradictory narratives in the film’s structure; the frequent inclusion of telenovela clips throughout The Devil Never Sleeps. These are the repetitions in Portillo’s documentary that unseat assumed meanings, like Oscar’s claim that the land in Chihuahua could “grow anything,” which is counteracted by an explanation about the inevitable damage his and other farms did to it; or, the drama of one aunt’s description of the brutal beatings little Catalita, from Oscar’s first marriage, received at Ofelia’s hands, which are undone by Catalita’s insistence that she doesn’t recall any of the sort and her stated desire to keep her family together. Most powerfully, the telenovela excerpts, like echoes of the “old stories” her relatives like to tell, reveal an enduring, if endlessly frustrating, quality of families like Oscar’s. Their memories appear full of drama and their theories rich with violence, passion, and betrayal, sufficient to entertain if not necessarily “true.” Perhaps this is also the truth The Devil Never Sleeps reveals about documentary investigations such as these and what they can provide when answers remain elusive.

The Devil Never Sleeps screens tonight, September 27, at the Museum of the Moving Image as part of the series “Personal Belongings: First-Person Documentary in the 1990s.”