The work of French director Jean Eustache belongs to the softly enraged and thoroughly disillusioned, those snubbed by the future, eternally at risk of being left behind. Glancing backward to the solid histories and traditions of the past, these are films of inchoate disappointment, occupying the threshold between anguish and apathy, fomented by the rotten fruits of imagined progress.

Arriving onto the scene in the twilight of the 1960s, Eustache’s work falls somewhere between the experimental French New Wave and the more confessional and realist work of auteurs like Philippe Garrel and Maurice Pialat, a fellow purveyor of raw disappointment. Born in 1941 to a working-class family in Pessac, a suburb of Bordeaux, Eustache, like Pialat, drew from his own experiences, conflating life and art. “A picture can be personally pornographic while being publicly decent,” someone says in his 1980 short, Alix’s Pictures, as if to describe the deeply intimate nature of Eustache’s films.

Dying by his own hand at age 43, Eustache left behind an abbreviated body of work anchored and overshadowed by The Mother and the Whore (1973), the tidally monumental and voluble 219-minute film that has been been namechecked by everyone from Claire Denis to Ira Sachs, Jack Nicholson to Harmony Korine. Film at Lincoln Center seeks to rectify this with its 12-film retrospective—two narrative features, a handful of documentaries and novella-length films, plus a shorts program—allowing audiences to engage with the filmmaker beyond his magnum opus.

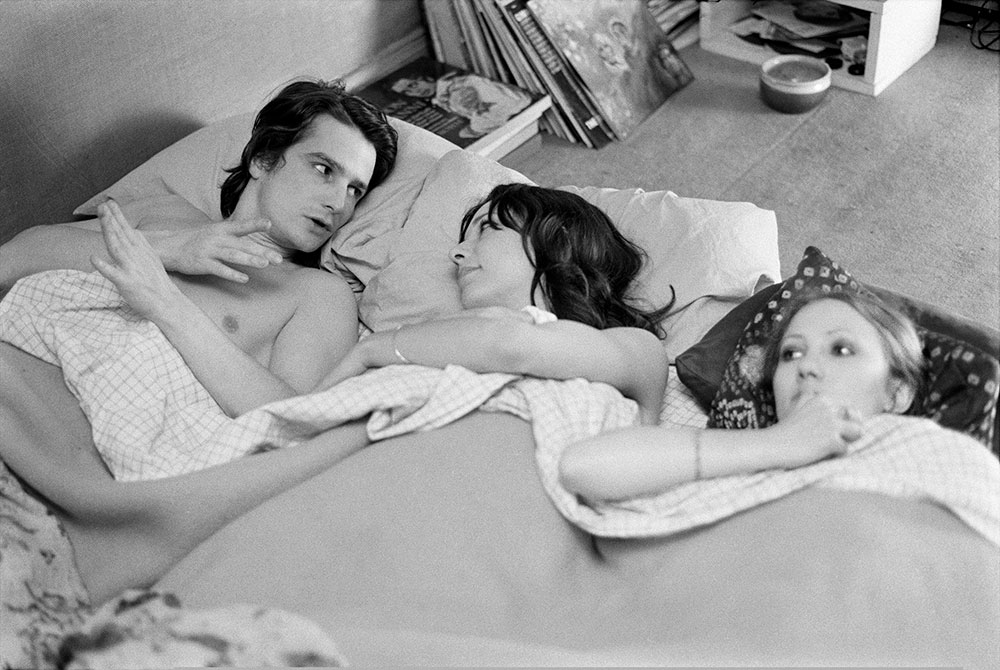

Eustache’s elegy for the failed revolution of May 1968, The Mother and the Whore maps the ensuing political indifference and ideological malaise of a generation onto the romantic conflicts of a sensitive dirtbag. Alexandre (Jean-Pierre Léaud) lives with the older Marie (Bernadette Lafont, somewhat cast against type, as the cuckolded woman) and courts the sexually liberated Veronika (a luminous Françoise Lebrun, in her breakthrough role). Eustache seeds the prospect of a ménage à trois, but the film is less than explicit; any trace of the erotic is intellectual and linguistic, derived from an uninhibitedly talky script. The dialogue—based on Eustache’s actual conversations, riddled with memorable quips and swirled with retrograde pessimism—becomes mesmerizing and cinematic, fueling the quiet propulsion of the film and its mostly static medium shots. Targeting progressive politics and specifically “women’s lib,” the film has an undeniably reactionary bent that evokes today’s anti-woke culture. But Eustache's self-effacing and unapologetic observations, and his trio's acute devastation, turn the film into a teeth-gnashing portrayal of anomie.

The oppositional forces of trollishness and tenderness in The Mother and the Whore can be traced to Eustache’s earlier works, like the spiritually connected Robinson’s Place (1963) and Santa Claus Has Blue Eyes (1966), which also follow the abortive exploits of penniless young men as they prowl pinball parlors, dance halls, and cafés in search of female companionship. In Robinson’s Place, two friends, failing to make it with a young divorcée, exact petty revenge by pinching her wallet. In Santa Has Blue Eyes, a young man (Léaud) hoping to buy a duffle coat, the trendy piece of outerwear du jour, works a seasonal gig as Pére Noël, and discovers in the process that the Santa costume endears him to women. (They seem not to mind the occasional fondling when they cozy up for a Polaroid—bad Santa, indeed.) Eustache builds scenes as brisk vignettes with an ethnographer's flair, assembling vérité sketches of Paris, from the ambient buzz of bustling streets to the lonely pallor of other corners. A sexual conquest does not materialize in either film and the characters, failing to achieve fulfillment, resort to small-minded and reactionary solutions. Eustache renders these pitiable louches mostly harmless, and suggests the skirt chasing is less the goal than a proxy for trying to sublimate class resentments. Writing in the Village Voice in 2000, Amy Taubin astutely identifies this strain of masculine anxiety in Eustache’s film, which has endured in Taxi Driver and in the work of John Cassavetes.

In A Dirty Story (1977) too much sexual fulfillment has the opposite effect. In this bifurcated 50-minute film, a man’s salacious obsession with a café-bathroom peephole and the untrammeled access it provides causes him to long, half-jokingly, for the Victorian Age—it sounds a lot like something Alexandre might’ve said in The Mother and the Whore. One part is given over to Jean-Noël Picq’s real-life accounting of his voyeurism; the other is a staged reenactment of the same by Michael Lonsdale. Picq also appears and monologues again in the short film Le Jardin des Délices de Jerome Bosch (1979), which also regards art and truth, this time vis a vis his description of the famous painting.

Eustache’s penchant for tradition is rooted in his documentary work, rigorous examinations that capture the old-world spirit. Le Cochon (1975) is a visual account of how the sausage gets made. A group of men set about butchering a pig, shaving its hair, bathing it with kettlefuls of water, pawing out the organs, and later grinding it out and encasing it, looped into figure-eight links. The events conclude with a well-earned meal, though we don't see it. Skipping to the dirty-dish aftermath, and finally, the house at dusk, Eustache emphasizes the artisanal process, the idea that the work is its own reward. In The Virgin of Pessac (1969) he films his hometown’s time-honored practice of crowning the most “virtuous'' young woman. Deliberated by the townsfolk and mayor, the ritual is a respectably innocent precursor to the modern beauty pageant that he would revisit a decade later in The Virgin of Pessac ’79.

Numero Zero (1971) is a home movie of sorts, in which Eustache interviews his bespectacled grandmother. She digressively chronicles her life, which includes colorful accounts of filching walnuts from a neighbor’s tree, watching her laundress mother wash clothes in the river, and contending with her husband’s affairs. Eustache’s reverence for her is clear as he politely pours her scotch and lets her take the conversational reins. Grand-mère’s impact on his life was also depicted in his second and final narrative feature, My Little Loves (1974, pictured at top), a Bressonian portrait of coming-of-age. Ravishingly shot in color by Néstor Almendros, the autobiographical tale conveys the dispiriting indignities of adolescence with a knowing sigh, and provides some clues to Eustache’s own upbringing. (“The only true pictures are of childhood,” to quote again from Alix’s Pictures.)

Daniel (Martin Loeb) experiences the rude awakenings of adulthood as he moves from the idyll countryside to Narbonne to live with his wraithlike mother (Ingrid Caven) and her Spanish boyfriend, so prone to silence as to seem catatonic. Their monumental indifference replaces his grandmother’s warm encouragement, and the wild grasses and open fields of his former home are soon supplanted by the dank confines of a garage. He is forced to work as an auto mechanic's apprentice instead of going to school, and his youthful hopes are nearly extinguished—only the possibility of romantic encounters proffers a sliver of hope. Ever resilient, Daniel sees to his own education, which is achieved through observation. At the movie theater, the promenade, the café, he diligently watches the older boys and eventually learns through imitation. Opting for plaintive gestures over overt drama, distanced empathy over easy sentimentality, Eustache forges a delicate and searing work of restrained compassion.

“The Dirty Stories of Jean Eustache” runs through July 13 at Film at Lincoln Center.