This year’s DOC NYC is the first virtual film festival that I’ve “attended.” Although nothing beats mingling with the usual mixture of grumpy festival veterans and starry-eyed festival neophytes and wrangling with overenthusiastic festival staff who love to corral crowds of people and bark sitreps into their walkie talkies, the abstracted experience offered by the virtual festival has merits of its own. For one thing, you can see a whole lot more. No more conflicting screening schedules, block-circling lines, or shuttles from one screening venue to another. (Unfortunately this also means no impromptu history lessons from talkative shuttle drivers or enthused moms presenting their mortified teenager who’s never been to a film festival before.) The shelter-in-place version means that, theoretically, you can watch all 200 films, binging the whole fest from under your duvet. Personally, I don’t have the stamina and was forced to choose only a handful of titles. Considering how much proverbial food for thought they ended up providing, I doubt I could have chewed down more.

Norwegian first-time director Magnus Skatvold worked for a handful of years on The Blue Code of Silence, a pure talking heads doc with an expensively licensed rock ’n’ roll soundtrack that is so formally orthodox that it evokes a unique pleasure of recognition, like a Marvel movie that hits all its beats flawlessly. The most facetime is given to Bob Leuci, a now-retired NYPD detective who, in the early 1970s, did bad things as a member of the short-lived yet notorious Special Investigations Unit and subsequently narced on his colleagues. Leuci still trains local police cadets in the vicinity of his Maine home but is no longer welcome anywhere near the NYPD. This is made abundantly clear by other retired cop interviewees, such as Kerry Schacht and Bob DiMartini, mustachioed 70-something goombahs who look and sound like they stepped out of Fort Apache, The Bronx. But the most fanatical vitriol comes from former NYPD detective Kathy Burke, who says things like “He sold his soul to save his ass,” and “I hope there’s a hell and he’s burning in it.”

The titular blue code of silence, the informal oath of secrecy that is supposed to protect cops from accountability, is effectively illustrated by the hatred these cops reserve for those from their ranks who’ve broken it. It also makes you suspect the validity of statements like Leuci’s, who claims to have had a crisis of conscience when he looked himself in the mirror and said, “I’m a policeman, not a gangster.” Skatvold’s film stops short of a conclusion that many of us reached this past May and June (if not years ago when the Black Lives Matter movement first began, or sooner): that any given American police department not only resembles an organized crime outfit in its worst moments; it is structurally impossible for it to be anything but an armed, well-funded, and tight-knit special interest group, and therefore by definition no more than a powerful organized crime association. Show me one substantial difference between a mafia protection racket and a police protection racket and I’ll enroll in police academy.

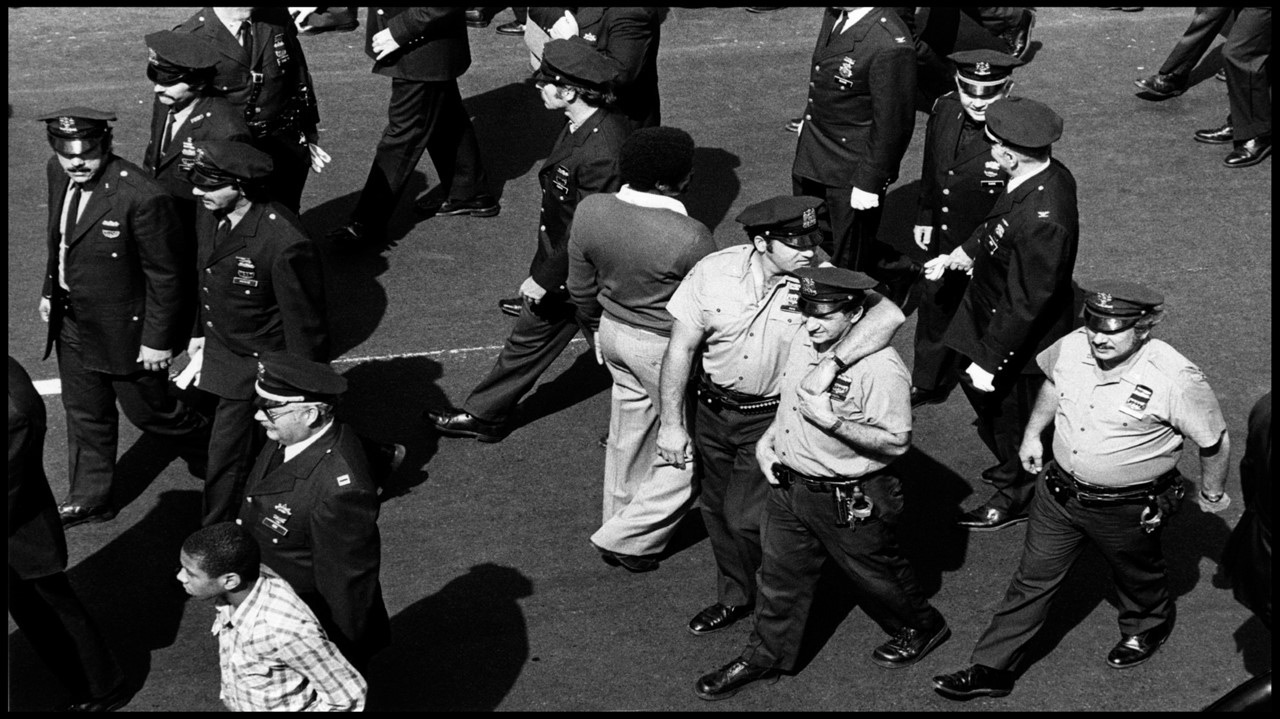

Skatvold’s access to archival footage (from sources like British Pathé, Magnum, Getty Images, and the NYC Mayor’s Office) is amazing. In this respect it calls to mind Swedish filmmaker Göran Olsson’s Black Power Mixtape 1967-1975 (2011), which makes great use of grainy but luminous footage of Angela Davis, Stokely Carmichael, and Fred Hampton, and Concerning Violence (2014), which compiles hours of restored newsreels from the decolonization struggles of Mozambique, Congo, and Angola. Either the Scandinavians have a preternatural gift for finding and presenting salient archival material, or their national film industries’ generous subsidies make such ambitious archival projects possible.

For a story about another code of silence, check out Marianne Hougen-Moraga and Estephan Wagner’s Songs of Repression, which tells the story of a German Evangelical Protestant colony formed in Chile in 1961. A veil of secrecy shrouded the so-called Colony of Dignity, and its leaders — including founding guru Paul Schäfer — got away with decades of systematic child abuse and other crimes. Arriving with the imprimatur of executive producer Joshua Oppenheimer, director of The Act of Killing and The Look of Silence, Songs of Repression has a similar approach. The filmmakers have spent enough time among their subjects to make them comfortable with opening up to them about both their traumas and their misdeeds; many of the original colonists’ children still live in the area, but while some of them have remained in the cult’s fold, others have chosen to distance themselves (emotionally if not physically) and begin processing their experiences with therapeutic support from other survivors.

We meet a gardener who is still a devout evangelist and dismisses as exaggerations the stories of Schäfer and company’s abhorrent behavior. She is a member of the small village choir, with whom she sings the titular songs of repression, i.e. traditional German Lutheran songs that, in their misty-eyed reverence for a paternalistic God, are so creepily infantilizing that they sent literal chills up my spine. We also meet a beekeeper who condemns Schäfer and the gang in no uncertain terms (“I can’t stand this pathetic charade anymore, it’s an outrage”) and admits that the word Gemeinschaft (German for “community”) now gives him the creeps. And we meet a man who has landed somewhere in the middle, working as a tour guide for the Colony of Dignity’s nascent tourism industry. By leading Chilean families through the cellars in which he and other children were beaten and sexually assaulted, this man simultaneously acknowledges the colony’s dark past and packages it as something gone and forgotten. Meanwhile, the families of the colony’s original “hierarchs” still run the place, and people they tortured and killed as volunteers for the Pinochet regime are still buried on the property in unmarked mass graves.

If you want to stay with the theme of authoritarian organizations, take a look at German documentarian Moritz Schultz’s Summerwar, a fly-on-the-wall portrait of a summer camp run by the Azov Regiment, an esoteric ultranationalist paramilitary organization that has been distinguishing itself in the war against pro-Russian troops in the Donbass region since 2014. Despite the group’s use of Nazi iconography (such as Himmler’s occult Sonnenrad, or sun wheel) and the militaristic hierarchy the camp is structured around, we're given a fairly positive feeling about the camp and the kids who attend it. Although 10-year-olds are made to bark slogans like “Death to our enemies,” they also form intergenerational friendships. Granted they spend some amount of time commando-crawling through ditches and learning how to disassemble and clean an AK-47, but they also do "normal" kid stuff like play video games on their phones and try to smuggle in candy from their parents.

The two main kids we follow are Jasmine and Jastrip, a girl of about 13 and a boy of 10. Jasmine’s loving, suspenders-wearing dad has such a timeless meat-and-potatoes Slavic appearance that he looks like a soldier from The Cranes are Flying, while Jastrip lives mostly with his grandma and feels neglected by his family. The film spends a good amount of bandwidth showing how, despite their contrasting backgrounds, they're both able to squeeze joy and a sense of accomplishment out of the experience. While their fortunes at camp end up eventually converging, there are several heartbreaking juxtapositions of their divergent domestic circumstances, such as Jasmine calling her proud parents to tell them about her promotion to squad leader while Jastrip’s parents don’t even pick up.

Some of Jasmine and Jastrip's camp friends have incredible names like Sprite and Fanta, Iskra and Talisman. (I’d love to see a Ukrainian book of baby names, circa 2008 edition.) We hear two of them sing a song about Ukrainian troops marching victoriously through Moscow’s burning ruins, then have a spontaneous debate about the idea of Ukrainian military expansionism. Are they training to conquer territory, or only to defend what they already possess? I’d love to see a sequel that focuses on the counselors, who, as people in their late teens, presumably have more clearly articulated political beliefs than their grade-school-age subordinates.

I wish I’d had the time to see dozens more titles from this year’s DOC NYC’s impressive slate, but I’ll settle for having the 2021 edition to look forward to — whether it’s virtual or not.