“Isn’t he beautiful?” These startling words are spoken by Sally, a once “big, healthy red head” who is now weak, without hair, and hospitalized with an inoperable form of brain cancer. She is one of three terminally ill people in Greater Boston documented with bracing frankness by Michael Roemer in Dying (1976). The question, addressed to no one and anyone, but ostensibly to a nurse nearby, is about a fellow patient struggling, like Sally, to walk, to live. He is a sick elderly man we see only briefly from behind. He is beautiful. It’s a normal enough utterance in another context, but here, spoken tenderly, unearthly so, it lands like thunder in a film calibrated to palpably render human frailty on screen, determined as it is to approach the invisible—the inner life of the mind, life after death—by the most material means. We are bowled over by the soft contradictions of these words. One thinks of the final line of Roemer’s debut fiction Nothing But a Man (1964), which emanates so quietly and so plainly from actor Ivan Dixon’s mouth that you wonder if it’s come from your own head, or from somewhere deep in the earth: “Baby, I feel so free inside.”

After Sally, there’s Bill, a father of two with melanoma. His slow decline is observed mostly from the perspective of his wife Harriet, spiraling in crisis. And there’s Rev. Bryant, a Black preacher whose cancer, he learns, has spread to his kidney. Since his earliest efforts, the weight of death has loomed in Roemer’s work. Present everywhere, visible nowhere, a feeling for the beyond is there, in spite of Roemer’s persistent refusal of abstractions and his intimate awareness of the limits of the camera: that it can record only what can be touched. His films, in turn, place a profound trust in the viewer’s capacity to read these surfaces and their secrets; as in the scene where Bill’s wig falls off while swimming with his family and he must labor to dry it in the company of his kids—a moment that condenses all of his mortality into one object. Dying will continually betray that we are in the hands of an eloquent, deeply emotional poet. Small, potent details in the film, flushed with color yet completely unemphasized, are inclined to bound off the picture plane and into our laps, quivering with their proximity to the dying: the red rose that Bill waters with such delicacy in his garden; the red house plant carried by Sally as she’s transported from the hospital to her childhood home, where she goes to die; the red hat of Rev. Bryant’s grandchild who holds his emaciated hand at his bedside.

After chronicling the physical toll of their illness, each of the film’s three episodes ends with an intertitle stating the date of the person’s off-screen death. It’s only at the end of the film that Roemer records the passage to the other side, when after the Reverend’s chapter—“Rev. Bryant died on Jan. 23, 1975”—the door is left ajar and we are made a witness to his funeral. In an unbroken long take, a train of faces, old and young, pass into view as they pay respects to the man in his open casket, alternately weeping, singing, recoiling. For Roemer, a materialist sage, here is the afterlife.

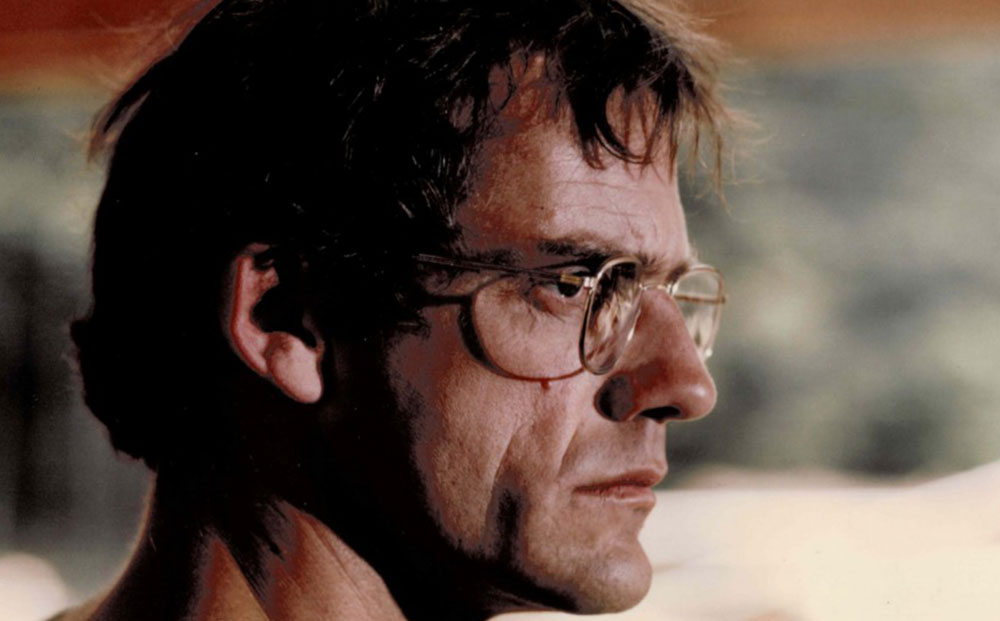

This image, of the world viewed from a coffin, is repeated in Roemer’s fictional Pilgrim, Farewell (1982) when Kate, dying from cancer, lies down alone in a narrow canoe out in a Vermont lake, peering up at the trees above and at the blue sky beyond. The scene is a memory, perhaps, of Vampyr (1932) by Carl Dreyer, whom Roemer knew personally. Dreyer’s Joan of Arc (1928) is also present in Kate’s close-cropped hair, a result of her chemotherapy; in her Falconetti-like stubbornness in the face of death; in the moment when her estranged daughter, in a similar emotional spiral as Harriet in Dying, takes scissors to her hair in a fit, only to be stopped by her mother: “There’s little enough hair in this family.”

Roemer once told me he sees no particular difference between his documentary work and his fictions, that they flow from the same spring. Pilgrim, Farewell was born from Roemer’s harrowing experience making Dying six years earlier. He takes the more diffuse tensions of the previous documentary and pressurizes them in a livewire kammerspiel. The intensity is such that Roemer needs to puncture the drama intermittently with landscapes, empty spaces that provide momentary reprieve. Some objects from the documentary are cited verbatim in the fiction, like the portable radio Kate carries everywhere playing Debussy, Satie, and Dvořák, that recalls a similar radio that never left Sally’s side in Dying. Even the color red bleeds from Dying to Pilgrim, in a brilliant scarlet parasol that is seen peripherally, but assertively, throughout the film.

All these continuities can now be observed, as both films are restored and being released as a theatrical diptych, a format that Roemer has insisted upon. They must be seen, because they are among the precious few works completed by a refugee since childhood, uprooted from his home by Nazism as an 11-year-old, who walks among us and speaks concretely of love and pain. To echo one of the final gestures of Pilgrim—the daughter packing up her dead mother’s reproduction of a Cézanne landscape and heading out to the mountains—I’ll end with something Cézanne said, as documented by his pupil Joachim Gasquet, which I think would resonate with Roemer the filmmaker:

You must remember the story of how the vines all over Palestine blossomed on the night Our Saviour was born…. We painters would do better to paint the blossoming of those vines than the whirlwinds of angels proclaiming the Messiah with their trumpets. Let’s paint only what we have seen, or could see….

Dying + Pilgrim, Farewell screen at Film Forum January 24-30. Michael Roemer will be in attendance for a Q&A on the afternoon of January 25.