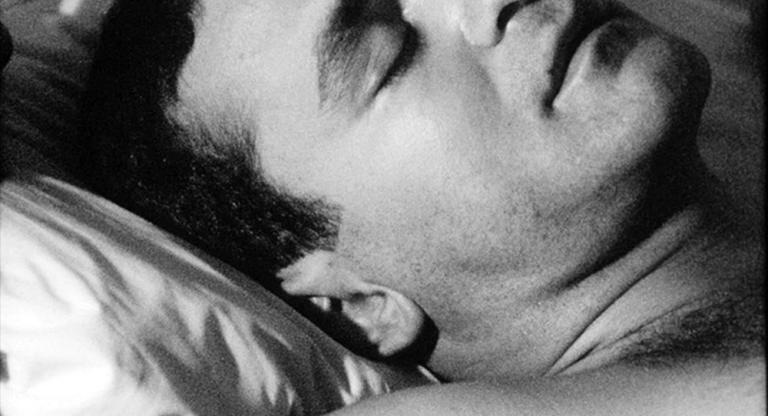

In the mid-1960s, Andy Warhol made a number of bodily “anti-films”: Sleep (1964), where performance artist John Giorno slept on camera for five-and-a-half hours; Kiss (1963), where multiple couples kiss for three-and-a-half minutes at a time, spanning an hour total; Drunk (1965), where documentarian Emile de Antonio downs a quart of scotch in 20 minutes on camera; Blow Job (1965), where theater actor DeVeren Bookwalter receives fellatio from someone offscreen, the camera capturing his behavior. One can endeavor to guess the subject matter of his film Eat (1964).

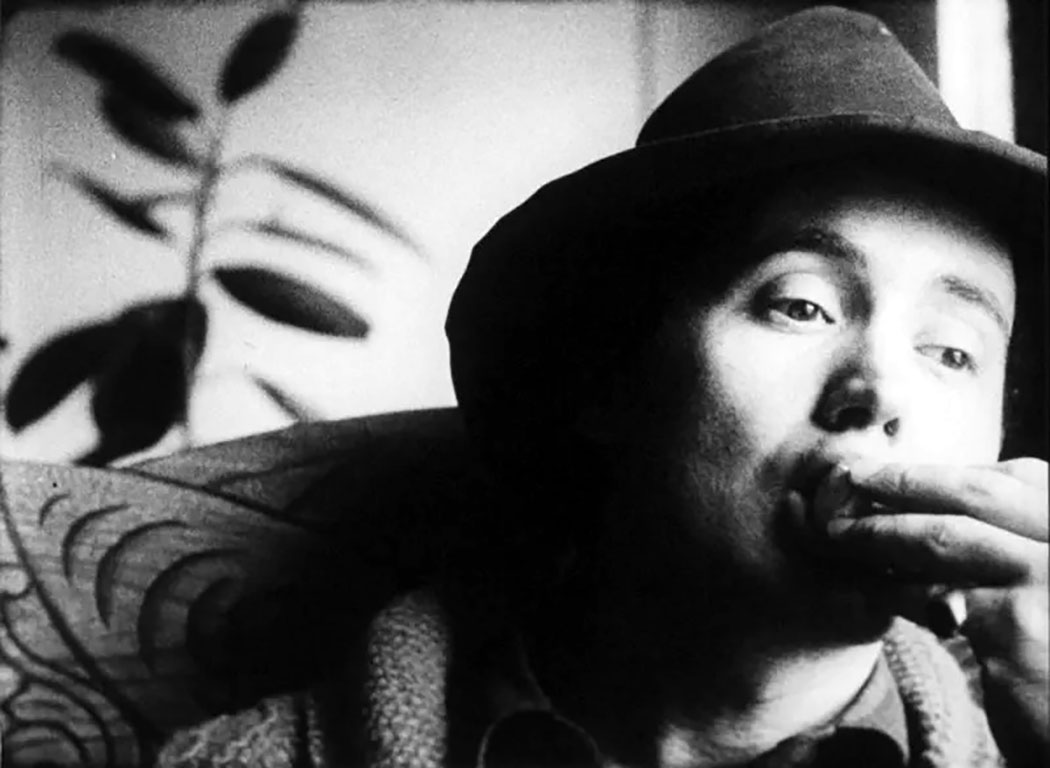

In the film, the American pop artist Robert Indiana (widely known for his LOVE sculptures) slowly eats a raw mushroom for 45 minutes. Shot in black-and-white with no soundtrack (though composer La Monte Young would later provide one for the film’s projection at the Film Society of Lincoln Center), Warhol strips pleasure and animation from the act of eating. Such was the extractive quality of experimental filmmaking of the era, which traded excesses of color and form for the flexibility of avant-garde minimalism. Eat, Sleep, and Kiss eventually formed a limp trilogy, a mediatic pivot from Warhol’s painting.

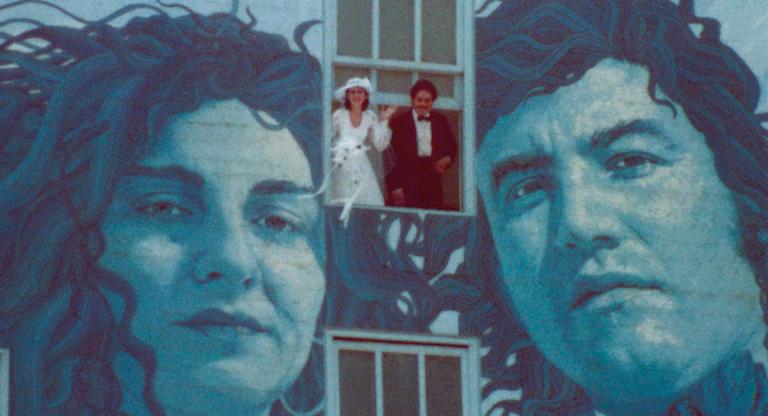

Meanwhile, Indiana began a series of paintings in 1961 that evoke the dynamic graphic design of American advertising—flush with primary color, pithy keywords, and national emblems. In 1964, the same year as Warhol’s Eat, Indiana created an “EAT” series for the New York World’s Fair, comprising a polychrome aluminum and stainless steel lighted sign called the “Electric Eat” which read “E A T” twice diagonally, as well as oil paintings titled “EAT,” “For,” and “Fork.” “The word ‘eat’ is reassuring, it means not only food but life. When a mother feeds her children, the process makes her indulgent, a giver of life, of love, of kindness,” Indiana tells Vogue in 1965.

So what of the masticated fungi hanging in Indiana’s jaw in 1964? What indulgences does Warhol’s Eat give us? Besides the postmodern workings of the film apparatus, Eat, like many of Warhol’s experimental videos, trains its viewer to vigorously examine the frame. Iterations of the same image loop until a welcome variation in form arises: pearls of overexposed light, Indiana’s cat skulking around his shoulders. How both artists arrive at the same subject, one acting on nostalgia and the other on retribution of form, is a riddle of digestion.

CONTOURS is a column by Saffron Maeve examining films that thematize the world of visual art: heists, biopics, documentaries, and experimental fare. Maeve also programs a screening series of the same name and premise at Paradise Theatre in Toronto.

Eat screens tomorrow evening, June 29, on 16mm at Anthology Film Archives as part of “Essential Cinema: Warhol / Watson & Webber / Whitney.”