Frederick Wiseman’s Essene premiered on Monday, November 13, 1972, not in a movie theater but on television. It was a PBS special, up against Laugh-In, Gunsmoke, Hogan’s Heroes, and Boris Karloff Presents. A film about life in a monastery, Essene was advertised in The New York Times with the heading “Peace,” indicating that the subject—the search for inner peace among men of God—marked a new direction for Wiseman in his growing series of documentaries about American institutions. But Essene is hardly awash in serenity. Wiseman finds plenty of tension between the monks, sometimes profound and sometimes petty, whether in spiritual or political discussions, or in charged human encounters. More than 50 years and 40 films later, the 95-year-old Wiseman, with the word “legendary” usually attached to his name, is far from underrated. But the recently completed digital restoration of his films, now being presented theatrically in retrospectives around the world, reveals the astonishing craft, structural power, and novelistic richness of his work—qualities that may not have been fully evident on the TV screen.

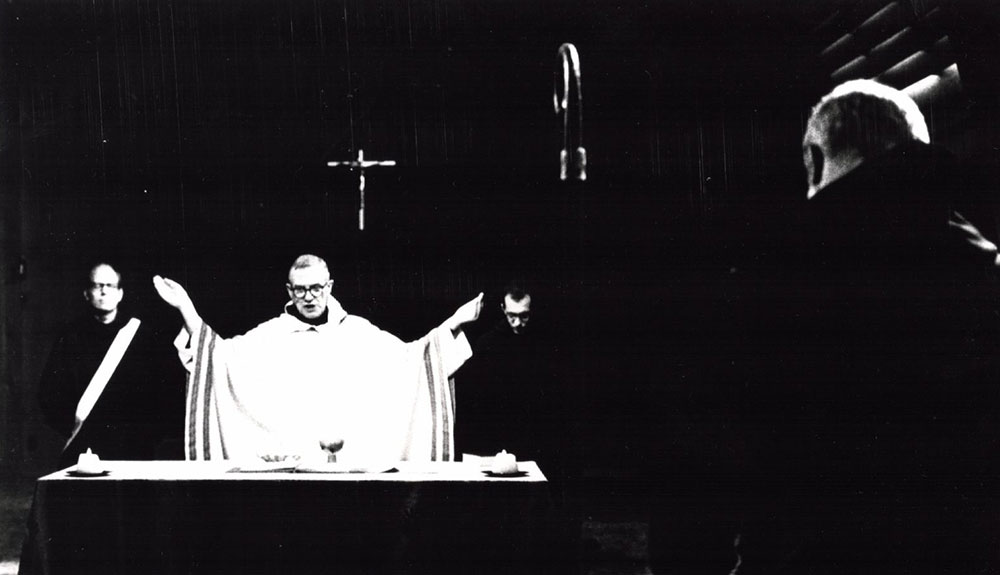

Wiseman’s true subject is not as much the institutions that he examines as the rich complexity of the people he films. Wiseman is, of course, deeply interested in the workings of the social structures that he immerses himself in. But for him, the institution serves primarily as a dramatic container: the place where society’s ideals and aspirations come up against the messiness of human psychology. The sacred meets the profane, and Wiseman views this clash with a clear-eyed existentialist’s blend of compassion and humor. In Essene, the drama is heightened by the remarkably intimate and expressive cinematography of William Brayne.

The film, whose curious title refers to an ancient Jewish sect that lived separately from a world they viewed as corrupt, was photographed almost entirely in a midwestern monastery that had established independence from the Anglican church in 1969, giving Wiseman the opportunity to attain access. The film opens on a bucolic montage, with quick shots of a tall, shirtless man gently raking leaves; of two men kneeling in prayer; of a monk contemplatively reading. But soon, conflicts are revealed, and emotions start to simmer out of control. Wiseman focuses on two men who are temperamental and generational opposites. Wilfred, an elder monk, seethes with anger in a meeting with the Abbot, the monastery’s leader, explaining that he feels disrespected when he is referred to by first name. Only his close chums, “of which there are five” are allowed to call him by his nicknames: Edmund, Ed, or Eddie. His petulant snit hardens, and he seems to close off emotionally as the conversation drags on.

In contrast to this tightly wound, seemingly rigid monk is Richard, a young man who can barely contain his emotions and constantly bemoans his inner anguish. Welling up in tears as he spills out his feelings to a sympathetic nun, it becomes clear that there is little distance for Richard between spiritual angst and sexual despair. Subsequent scenes deepen our feelings for these troubled souls. In a baffling but delightful excursion outside the monastery, Wilfred runs errands in town, visiting a hardware store in search of a potato peeler. Off the grounds, he becomes a different person; his formality drops as he engages in playful banter with the store owner, who keeps referring to him by first name (weirdly and mistakenly calling him “Herb.”) After his breakdown with the nun, we see the genuinely spiritual side of Richard, who is shown singing a heartfelt, beautiful rendition of the hymn “Deep River.”

In a sermon that abruptly but perfectly concludes the film, the Abbot contrasts Jesus’s “two close friends,” Martha and Mary. The former is controlled by ego and feels overwhelmed, plagued by the disconnectedness of things around her. Mary, on the other hand, has the wisdom to remain calm, and to remove ego, finding an ability to step back and understand the unity and profound mystery of creation despite its contradictions. Here, the Abbot could be describing Wiseman’s approach to filmmaking: his ability to look closely, without preconception, and to be open enough to sort through chaos and find some kind of sense in the world he observes. In Essene, among his most distilled and beautiful films, he does this with the lucidity and sheer emotional intimacy that makes him such a great artist. He reveals the wisdom of a saint.

Essene screens tomorrow afternoon, February 23, at Film at Lincoln Center as part of the series “Frederick Wiseman: An American Institution.”