I love America. I love America the beautiful because she’s still young and naïve and drunk with opportunity. But like a beautiful teenager (who everyone wants to fuck), she says a lot of stupid things (that everyone chooses to ignore). During the past few years there was a trend—hopefully past its peak now—that tried to make fascism seem cool, based. But like everything America touches, these ideas of fascism, Catholicism and monarchism are Disneyfied caricatures of the European originals. A girl wearing a holy trinity bikini set.

I spent my childhood in a Spain still adapting to democracy after forty years of fascist Catholic dictatorship. So it’s funny to me to imagine fascist repression as something colorful. To me fascism is gray, claustrophobic, and heavy on the chest, like the moments before a summer storm. That very moment when the air smells bad.

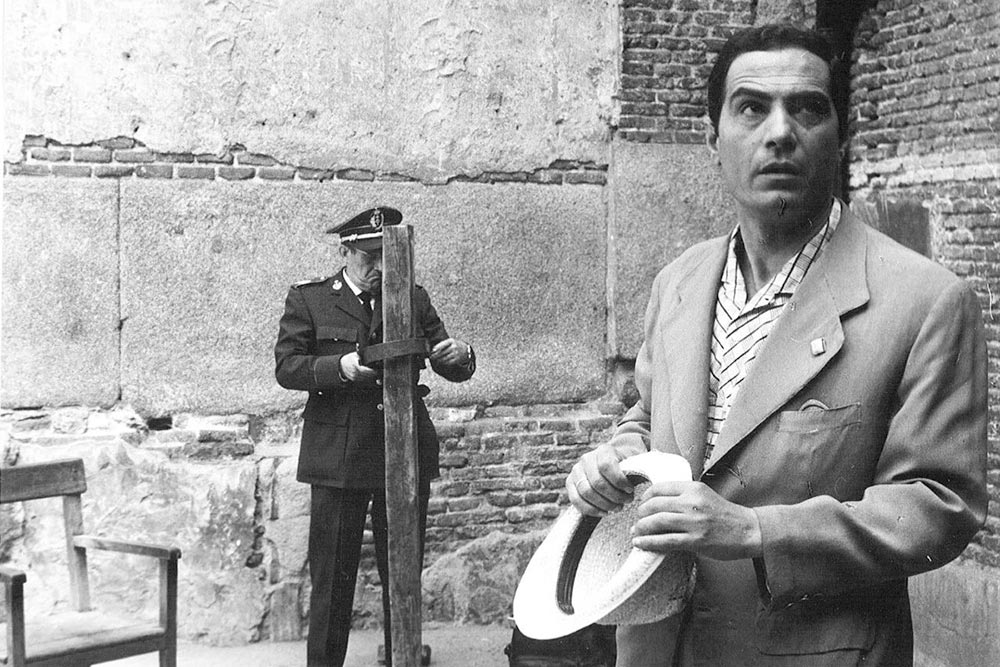

Every film in this series embodies this stuffy claustrophobic feeling, but only Luis García Berlanga’s The Executioner (1963) was actually made during a dictatorship. Everyone knows Buñuel, Picasso and Dalí because they expatriated and flourished abroad. But I have respect for those who stayed, like Federico García Lorca.

Unlike other writers and filmmakers who used minimalism and gloom to get past the censors, who interpreted their materials as harmless, boring works (Carmen Laforte’s Nada or Carlos Saura are good examples of this), Berlanga used satire and an endearing, relatable representation of the common folk that probably passed as inoffensively sweet to the authorities. Contrary to his films post-dictatorship, where the director overindulged himself in a raunchy, almost Benny Hill eroticism and a lot of political inside jokes; his dictatorship films (which relied on the support of the international community) are wonderful balancing acts in self restraint that often resulted in perfectly crafted, universal, timeless, dark comedies. Although I love his Destape1 era films, my favorite Berlanga is the subtle Berlanga.

Even though The Executioner is obviously about the death penalty and there are many direct references to the tedium of living in Spain during the dictatorship, there’s one moment that represents falangist Spain better than any other. When the young couple goes on a picnic, they step away to flirt and dance to the popular tunes that fill the park’s air. When the owners of the radio see this, they shake their heads in disapproval and, castrating their own fun, turn the music off, get up and leave, after imparting their lesson: if you want to dance, bring your own music.

To this, the protagonist whistles a tune so his girl can continue dancing with him, pretending everything is okay, even though the world is closing in on them.

The Executioner screens tonight, August 19, and on August 22, at the Roxy as part of “Desire and Punishment,” a series on fascism curated by Amalia Ulman that also includes the titles: The Holy Girl, Lucrecia Martel (2004), If…, Lindsay Anderson (1968), and The Piano Teacher, Michael Haneke (2001). You can buy tickets and read the full essay on the Roxy’s website.

1. El Destape is a cinematographic movement in the Spain of the late 60s that emerged when censorship became more lax. The name El Destape, which translates as to uncover, was taken quite literally and resulted in a lot of unnecessary female nudity and crass sexual humor. It wasn’t uncommon for actresses to be randomly topless in a scene that didn’t call for it and for that to be precisely the comedy in the film.