The Fast and the Furious: Tokyo Drift, the frequently and unfairly maligned third installment in the blockbuster franchise, closes out Japan Society’s series "Tokyo Stories: Japan in the Global Imagination." Like most other major action franchises, The Fast and the Furious has expanded globally in terms of set pieces; its chapters don’t really take place somewhere as much as they visit exotic locales in order to tear through them in elaborately choreographed stunt/driving sequences. For its often stilted acting and cheesy pondering over what it means to be an outsider, Tokyo Drift is a film interested in place. And Taiwanese-American director Justin Lin (Better Luck Tomorrow), who continued to direct the subsequent three sequels, took a script that was “about cars drifting around Buddha statues and geisha girls” and emotionally grounded it in its setting.

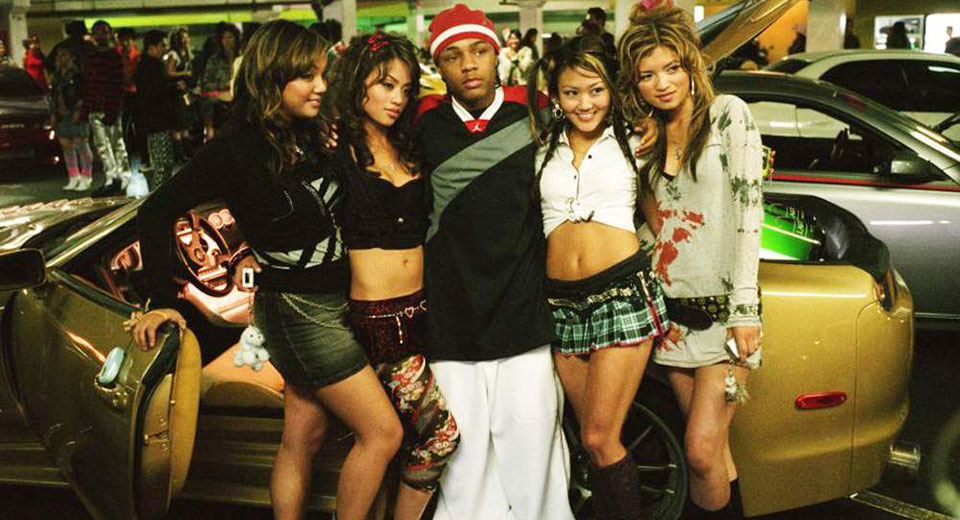

Tokyo Drift begins with corn-fed Sean (Lucas Black) getting sent to live with his estranged father in Tokyo in order to avoid juvenile detention for illegal street racing. The film’s opening race scene, with Kid Rock blaring over muscle cars kicking up dust and dirt, can’t help but appear self-aware of the series’ early image as Big Gulp-fueled American macho cinema. Sean’s auto-abstinence is short-lived as he meets Twinkie (Bow Wow), a military brat who introduces him to the drifting scene, characterized by racers who throttle to oversteer their cars around sharp turns in city streets, windy mountain roads and even parking garages. Sean quickly gets in over his head with Neela (Nathalie Kelley), the love interest, Takashi (Brian Tee), the Yakuza-associated rival and “Drift King,” and Han (a standout cool performance Sung Kang), who it turns out will be a F&F major player. A subplot involving Yakuza power-struggle is convoluted and forgettable, and is overshadowed by the enjoyment found in watching new friends grow closer while driving cars and exploring Tokyo.

Within the context of the Fast and the Furious world itself, fans often single out Tokyo Drift as the black sheep of the bunch (save for a brief cameo by Vin Diesel, all of the cast members are new additions), while acknowledging that it rejuvenated the franchise. It is the first film to ascertain the tenor that would come to define the series: the constant toggling between absurd spectacle and blunt earnestness that would famously center the movies around fuel and family. However, unlike its predecessors, which are more heist/cartel crime films, and its descendants, which propel the earlier main characters into global espionage missions, Tokyo Drift never loses track of being, first and foremost, a car movie. And by that I don’t just mean a movie that fetishizes cars (although it certainly does do that with every sensual camera pan over shiny chrome), but a movie that captures people loving cars, how cars can broker social relationships, and what it actually takes to be “good” at driving them. The ultimate delight to be found in Tokyo Drift is in its cars, which move gracefully synchronized around both quiet mountain sides at night and, most notably, through busy Shibuya Crossing in the film’s climax. The simplicity of its popcorn fun combined with an aspirational gaze at what it feels like to find pleasure in one’s environment makes this action oddity quite satisfying.