I have been doing a lot of catching up this January, as I often find myself around a lot of bright and learned film critics and film viewers whose history with the artform exceeds my own. The sense of shame that engulfs me whenever they discuss films I have never seen, or never heard of, has to do with my own warped sense of self-esteem. Discussing this on paper has no value for the public, so I’ll save that for when I can afford a therapist again. What I will do is argue that as cinema—and by this, I do not mean artsy box-office successes such as Babygirl (2024) and Nosferatu (2024)—becomes less important in culture, the cinephile’s culture in cities like New York runs the risk of ossification. The problem is one of concentration, of cinephilia as an echo chamber.

It is difficult not to recognize the hubbub surrounding the designation of Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975) as the best film of all time by Sight and Sound three years ago as ridiculous. More ridiculous is the fact that that coveted spot was occupied by Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane (1941) for most of the time that list has been published. Even more ridiculous is how much I have tricked myself into caring about these matters, and how much they appear to influence filmgoers living in such small circles as ours. Absent from my litany is a discussion surrounding how much distribution has changed since the publication of Sight and Sound’s 1962 list, when Citizen Kane was first awarded the honor of being the greatest film of all time. Jeanne Dielman’s disruption of the system is welcome because it posits that in the age of torrents, Criterion Channel, and whatnot, the canon is bound to be reconfigured. What is not welcome is that such lionization of a great film can rob it of its value in a public setting; suddenly, Jeanne Dielman is not a revelation, but an expectation.

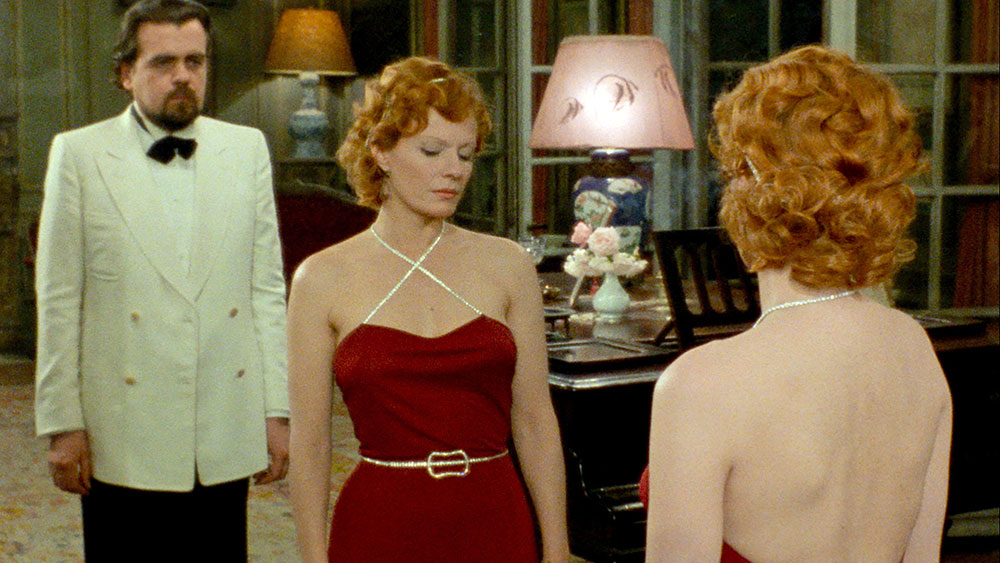

On Saturday, January 11, I attended a midday screening of Jeanne Dielman on 35mm at Metrograph. The crowd was attentive and polite. They walked in, sat for a while, and walked out with a seeming newfound air of erudition about them. Their attendance played out as a cultural task. As far as I could tell, there were no walk-outs. A week later, I attended Metrograph again for a presentation of Marguerite Duras’s India Song (1975, pictured at top) around the same time. Akerman and Duras’s strategies as filmmakers are distinct, but they both lean on duration to make many of their points—about labor and languor. Both films also star Delphine Seyrig. Nevertheless, I heard incessant shuffling throughout India Song, and I take this antsiness as a sign of real viewing—of embodied and contested feelings. This screening was also much emptier.

Expecting a similar audience and reaction to any two films is foolish, but it does strike me how canonical films are viewed as though to be check-marked or logged these days. It could be that no one has the time to talk about anything anymore and that the event of viewing a film has become the limited and necessary break filmgoers need from the world right now, but it did strike me to see people sitting around talking after watching Michael Roemer’s Dying (1976) at Film Forum on a Monday evening, while walking away in silence from showings of Jeanne Dielman, Taste of Cherry (1997), and Rosaura at 10 O’Clock (1958). (The latter, though virtually unseen in the United States, already carries the sign of canonization; its own filmmaker compared to Orson Welles in the pages of this publication.) Since all of the latter screenings I mentioned were very well-attended, while Dying and Pilgrim, Farewell (1982) brought in moderate audiences on a Monday night, I do not believe it would be a stretch to call the general audience of arthouse cinemas in New York—not its most ardent cinephiles—risk-averse. I hope the fact that Spike Jonze’s Her (2013)—pretty much the most obvious pick for a series about artificial intelligence you could think of—selling out the biggest theater at Film Forum reasserts how dire this risk-averse attitude can be for the city’s cinephile culture. If people are going to the movies to watch things they know are recognized as “good” or films they simply kind of remember because they were vaguely popular about ten years ago, we have a problem on our hands. The problem with catching up on the classics is that very little room is left to challenge the classics. And because the classics are well-attended, and inevitably bound to leave patrons of the arts with good impressions, they get recycled.

I did a lot of catching up this month and it mostly left me sad—about the fact that I hadn’t watched these films earlier, about what other films should be watched by more people, and about what other films I was missing out on by watching the films I was supposed to be seeing. It is my understanding there’s a Karagarga freeleech this week, and although I’m not one of the selected few with a personal account on this file-sharing website, my run-in with enough learned film critics and filmgoers has made me a sort of learning leech who takes advantage of his friends’ accounts to watch films I could not access anywhere else. I imagine this is a position shared among many in New York’s cinephile circles and I would urge people to both ask their friends to continue downloading films that are off the beaten path and nudge viewers away from heading out to watch what they think they should be watching and toward that which they never knew existed.

Feedback Loop is a column by Nicolas Pedrero-Setzer reflecting on each month of repertory filmgoing in New York City.