I attended a 35mm presentation of Alex Proyas’s I, Robot (2004) last week. I could have caught a 35mm print of Carl Theodor Dreyer’s Gertrud (1964) at Anthology Film Archives or the Polish filmmaker Edward Etler’s retrospective at e-flux instead, among other rare film screenings, that same evening. But, for reasons I am still trying to understand—ones that run askew of logic—I watched I, Robot.

There was a part of me that hoped watching the film 20 years after it came out would reveal a certain genius originally lost to critics at the time of the film’s release. That was not the case. I, Robot, being the result of a difficult production characterized by creative disputes between its maker (Proyas) and financier (20th Century Fox), is a jumbled mess. Although such incidents occasionally produce interesting and unclassifiable films, as is the case with titles like Waterworld (1995) and The Island of Dr. Moreau (1996), all I, Robot has to offer is an efficient example of formula-based filmmaking; the film delivers an obvious murder mystery with a romantic subplot and the occasional action set-piece in under two hours. In other words, it is designed to entertain and be forgotten.

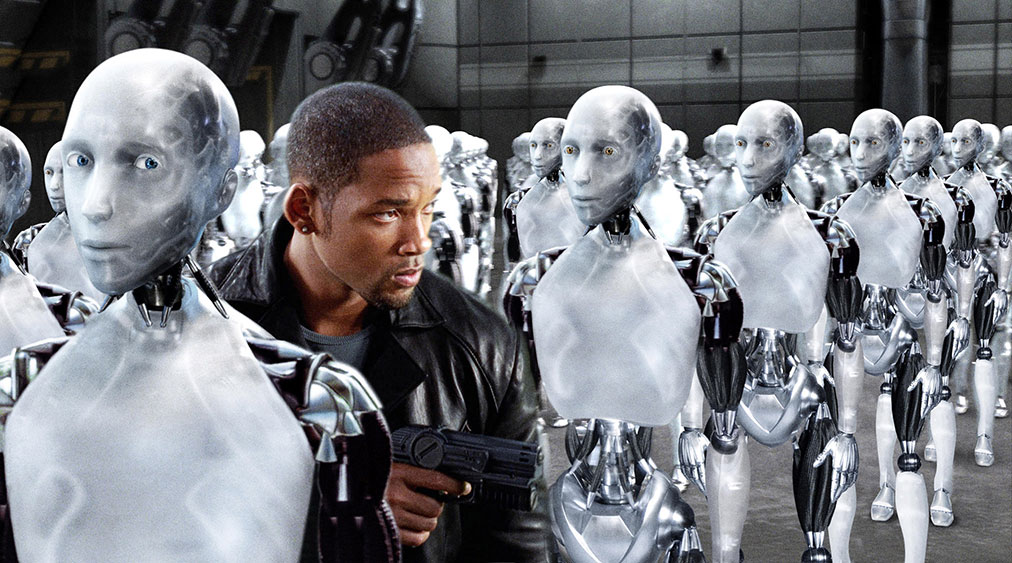

And the truth of the matter was that I was entertained. There is something ridiculous and endearing about seeing Will Smith antagonize generic-looking androids fifteen years before he faced off a heavily-rendered CGI-version of himself in Gemini Man (2019). But, there is also something refreshing about seeing an original big-budget sci-fi spectacle made by a major studio after a decade or so of indistinguishable franchise slop—be it Marvel, DC, Star Wars, or the short-lived MonsterVerse that gave us Tom Cruise’s The Mummy (2017).

Even so, and although I have called the experience of watching I, Robot refreshing, it goes without saying that there is nothing dignified about opting out of watching a new release like Piece by Piece (2024) or Venom: The Last Dance (2024) to catch I, Robot just because you suspect it will make for a slightly more enjoyable night at the movies. All of the aforementioned films listed are terrible, but at least viewing the latter doesn’t make you feel like you’re buying into the corporate scheme that has razed all signs of ingenuity in today’s cinematic landscape in order to promote homogenous content that cannot even hide its qualitative decay anymore. After the same commercial formulas have been used to churn out five Lego films in 10 years and three Venom films in six years, it’s inevitable that their latest outputs show signs of absolute degeneration; critical consensus has it that Piece by Piece and Venom: The Last Dance represent the saddest affairs in their respective corporate continuums. To quote friend and fellow programmer Steve Macfarlane on the last decade of film releases: “It’s bleak.”

If the contemporary film landscape is bleak, it goes without saying that its audience has also grown cold and despondent. As the writer Abe Beame establishes in his recent article about the uptick in repertory programming across the United States, “The Future of Film May Just Be Old Movies,” there is a correlation between the state of new film releases and filmgoers’ urge to seek comfort in old films. Although this has been generative for film programming in New York City because it incentivizes risk and exploration on behalf of programmers and audiences alike, it is also my suspicion that it has transformed New York’s filmgoers into a bunch of turtles that take shelter in dark auditoriums. The seclusion of the cinephile is nothing new—“the solitude of the cinephile has an asocial side that poorly prepares one for the seriousness of political work and the modesty of activism,” wrote Serge Daney in the ‘70s—but it seems most acute right now, partly because our deteriorating political reality shows no signs of remedy and partly because watching films has become a game akin to Pokémon where studious young devotees of the artform chase one rare screening after another in an effort to catch ‘em all. Letterboxd acts as their Pokédex.

After the screening of I, Robot, I was asked whether I’d seen the film before by another patron. I had. He hadn’t. What followed was a compliment about the number of films I’d seen despite my young age. It’s the kind of comment I’ve heard plenty of times at screenings all over the city, whether that be directed at me or at others. It’s also the kind of comment I do not care for because it transforms filmgoing into arithmetic; it makes conversations about cinema, which is to say conversations that should develop in an organic and unpredictable fashion, into a sort of associational ping pong. “Have you seen this?” “Yes, I’ve seen this. It reminds me of that.” “Ah, yes, that is kind of like this. It makes me wonder what else is like this.” “We’ll, I guess we’ve got to watch more of this and that to find out.” So on and so forth.

Perhaps my reaction to such a question is unwarranted. After all, it’s a rather benign question to ask. But having heard it at BAM two nights earlier after a 16mm presentation of Frans van der Staak’s People Passing Through Me in an Endless Procession (1981), the question genuinely alarmed me, because it made me realize that I have been operating according to the same viewing policy as everyone else. On the 22nd of each month, I typically have dinner with my girlfriend to celebrate anniversary. Except this month, I told her that my work demanded I attend the presentation of two extraordinarily rare Dutch films that might never be shown in New York again (this part, to my knowledge, is true). Thus, I postponed dinner to the next day in order to catch two films by a filmmaker whose work I’d never seen before out of sheer compulsion. Whether she reads this or not, I’ll find out soon enough.

I only ended up catching one film from the van der Staak double-bill because I got stuck on the Q-train for half-an-hour—perhaps a bout of karmic retribution. My recollections of the evening paint a clear picture of the sad urges that occasionally consume a cinephile’s sense of judgment, at least in their contemporary iteration. I had not seen People Passing Through Me in an Endless Procession and I had to because my ritual of filmgoing had also come to prize private consumption and intellectual self-aggrandizement over a more genuine engagement with films and a desire to share them with the world. Though genuine curiosity led me to that screening, hearing someone ask another person whether they’d seen the film after it ended made me wonder whether the only reason I was there was to be able to answer “Yes” to the same question in the future. Though contemptuous of the compulsive principles that govern contemporary filmgoing in New York, there I was conforming to its expectations by seeking out another rare film only to affirm it had been seen.

In the article I referenced earlier, Film Forum’s repertory film programmer Bruce Goldstein describes young moviegoers’ attraction to 35mm presentations as “fetishistic.” It’s an expected statement from someone speaking on behalf of the theater that hosted “This is DCP” back in 2012, but it’s not entirely untrue. There has always been a fetishistic edge to cinephiles, especially in a city like New York where they are spoiled for riches. This is what keeps the city at the cutting edge of repertory film programming, with programmers and audiences alike practicing an unrivaled resoluteness to rediscover cinematic treasures that run the risk of being forgotten.

The issue with the statement about this attraction to 35mm presentations, which have become specialized screenings in a day-and-age when DCPs dominate the repertory film scene, being “fetishistic” has to do with its framing. The likening of this “fetishistic” drive to “a hipsterish kind of thing” betrays New York cinephiles’ passions by chalking up their interests to a sort of role-play. Perhaps this is true right now, at a moment when people are willing to queue for four or five hours to buy BluRays in Criterion’s new mobile closet, or as I doubt my own intentions as a filmgoer unsure as to whether he is watching films out of personal conviction, in accordance with a tacit social agreement, or out of sheer panic that these are the last days of watching good films. The logic follows that a cinephile can collect viewing experiences in much the same way a hipster collects vinyl, but I refuse to admit that’s where the future of filmgoing is headed.

Earlier this month, I attended a screening of A.K. Burns and A.L. Steiner’s Community Action Center (2010) at Light Industry. It is safe to assume that the large crowd in attendance was partly there because of how rare the showing was. Community Action Center is a film that requires it be shown to two people or more. It is also pornographic, though it rejects the logic of contemporary porn viewing—an activity typically done in isolation, where sexual gratification is derived from anonymized bodies playing out trite and troubling scenarios. Instead, Community Action Center is a porno meant to be watched alongside other people, where pleasure is gained from its generous subversions of pornographic clichés and the feeling of solidarity that accompanies seeing these scenarios play out while sitting with others. The experience is such that it forces the viewer to think beyond themselves—beyond their filmgoing schemes or private pleasures.

Unlike other screenings I attended this month, when Community Action Center ended people laid back at Light Industry instead of shuffling straight out into the night. It helped that the film was presented by MIX NYC, a queer experimental film festival with a built-in community, because this facilitated conversation after the film ended. Although a fetishistic impulse might have taken me to Light Industry that night—the need to watch a rare film I’d only ever read about, one that was surely unlike anything I’d ever seen—that no longer mattered by the end of the night. The community, as well as the film, had overtaken me and I could not think of Community Action Center as just another film to log or checkmark in my life because that would betray the interactions that surrounded me that night. At the end of this screening, attendees weren’t asking each other whether they’d seen the film before, but actively parsing out their experience. Here lies evidence of another direction filmgoing can take: in favor of community rather than collective disregard for one another.

Feedback Loop is a column by Nicolas Pedrero-Setzer reflecting on each month of repertory filmgoing in New York City.