The month of May, which so often beckons spring renewal and remains synonymous with protest and solidarity action, saw a deluge of film programming concerned with aesthetic experimentation, historiographic interventions, and calls to action in New York this year. Though obvious praise is in order for another tremendous year of Prismatic Ground (full disclosure: Screen Slate is the official media sponsor for this annual showcase of experimental documentary and avant-garde film), several film series at multiple film venues across town staked claims for different ways of understanding history, making films, and living our lives.

Anthology Film Archives’s “Cinema of Palestinian Return”—co-programmed by writers Kaleem Hawa and Nadine Fattaleh—explored the traditions of narrative filmmaking vis-á-vis Palestinian life after the nakba of 1947-49. Set against the predominant association of Palestinian cinema with documentary filmmaking—a position typified by Jean-Luc Godard’s famous claim in Vivre sa vie (1962) that following the nakba, “the Jews became the stuff of fiction, the Palestinians, of documentary”—this series provided viewers with a window into the political depth fiction filmmaking is capable of. Not only did Hawa and Fattaleh’s series make known another side of Palestinian cinema, offering a new point-of-entry to those who denigrate agit-prop documentaries as lugubrious ventures of mere historical significance rather than as rousing testimonials that showcase radical political action and cinematic practice, it advanced a global project engaged in uplifting and upholding the history of Palestine, which remains under an existential threat that must—and has always been—countered through an insistence on resistance and direct action by global solidarity movements.

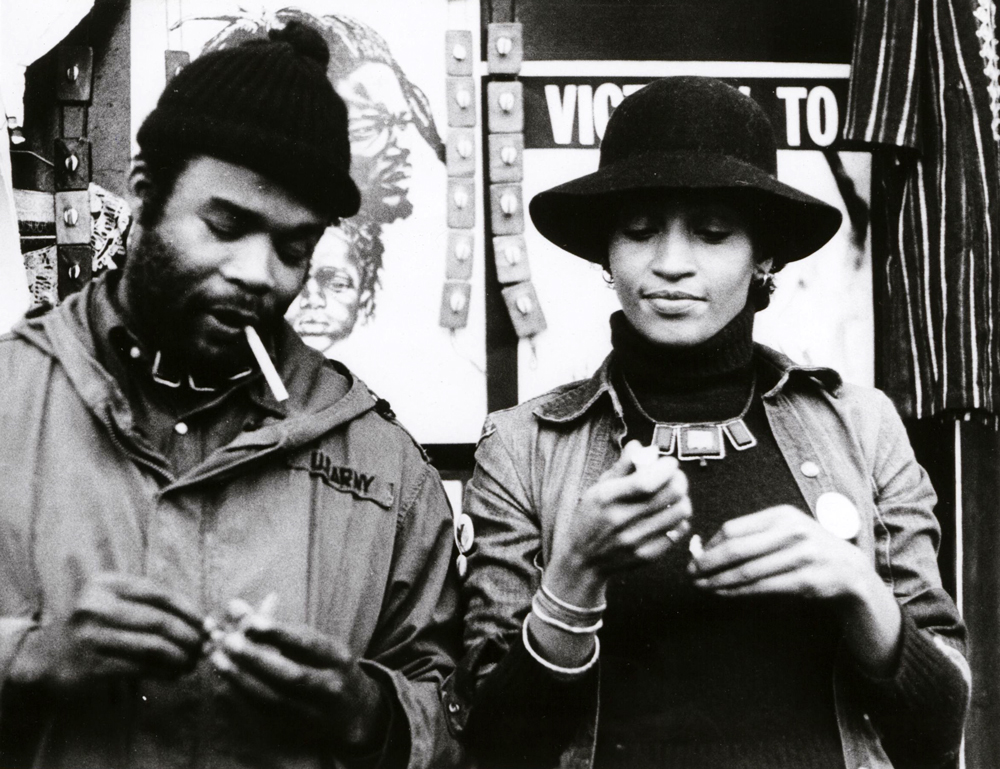

At BAM, curator and film critic Ashley Clark programmed a series titled “Uncharted Territories: Black Britain on Film, 1963 - 1986.” The series, which was organized around the re-release of Horace Ové’s recently restored Pressure (1976), a political portrait of a young Black man struggling to find his place in the world while exploring London, brought together a treasure trove of films detailing Black British life and experiences from the ‘60s to the ‘80s. It is my sense that these films’ grouping as part of this program, as well as the increasing engagement with the legacy of Black film workshops supported by Channel Four Television such as the Ceddo Film and Video Workshop, the Black Audio Film Collective, and Sankofa, represent a growing desire to rewrite Britain’s film canon among audiences, programmers, and critics. Moreover, I think this tendency extends beyond Britain. Given the moment we are currently experiencing registers as a historical terminus for the unsustainable ways in which our world has been power-brokered, it’s only natural for cultural tastemakers and audiences to interrogate the existing film canon—which is primarily white, male, European, and, for the most part, overly-invested in narrative filmmaking—and consider a society of opposites, dictated by the political desires and aesthetic interventions of those filmmakers who have been scrubbed from the history books.

Perhaps, this explains the increased attention given to the unsung figures behind films produced in nations with strong cinematic traditions. Here, I’m thinking about the Museum of the Moving Image and Japan Society’s monumental program devoted to the filmmaker Hiroshi Shimizu, Anthology Film Archives’s recent series dedicated to Marguerite Duras, and the Museum of Modern Art’s monthlong tribute to the French icon Bulle Ogier. Although these three figures represent wildly different artistic ingenuities, up until recently, they were not the first people you’d think of if Japanese cinema or French cinema came up in conversation.

During a conversation I shared with Ashley Clark about his “Uncharted Territories” series, he noted that in his twenties, when he was first coming into contact with many of the films he included in his series, you really got the sense that films were not just forgotten, but lost altogether. “I remember reading about Chameleon Street [1994] in Ed Guerrero’s Framing Blackness and being absolutely convinced that I would never see this film,” he told me.

The thought that a film might be forgotten exculpates people from its marginalization, but the admittance that films as great as Chameleon Street or as thought-provoking as those directed by Duras, those acted in by Ogier, and those gorgeously realized by Shimizu, can be lost from the cultural conversation that staples films to a historical canon reflects a tragic tendency to sideline works of art that do not cohere with dominant narratives in contemporary history. This is changing. In fact, this pendular shift might even go too far as films cease to be thought of in relation to their artistic ambition or political subtext, and are simply grouped in accordance with the color of their poster or shared narrative flourishes on platforms like Letterboxd, where tastelessness has become its own curatorial principle. Yet, hope remains. At the same time MoMA was presenting its tribute to Bulle Ogier, it also hosted the first leg of a retrospective dedicated to experimental filmmakers Nathaniel Dorsky and Jerome Hiler, that jumped over to Anthology Film Archives soon after. The sold-out showings at both venues—in addition to the attention given to Cecilia Vicuña’s videos at a well-attended screening at Triple Canopy’s shared offices with Electronic Arts Intermix; the warm reception of queer shorts curated by Sam Ashby at Hauser & Wirth; and, the flurry of contemporary filmmakers whose work is actually being screened at The Whitney for the first time in forever—suggests audiences are craving news ways of seeing and arranging films, and that they are seeking artists whose work does not cohere with timeworn cinematic traditions.

Tonight, you can catch a rare screening of Marin Karmitz’s Blow for Blow (1972) at Metrograph. As far as I can tell, the film hasn’t screened in New York since 2014, when MoMA presented it as part of “Carte Blanche: MK2.” It’s a riveting film that depicts a female workforce at a textile factory in France occupying their factory. Its vérité approach makes it an interesting counterpoint to Jean Luc-Godard’s Tout Va Bien, which was also realized in ‘72. But, while the latter is well-known—and for good reason—the former remains neglected. And yet, today it inaugurates a series dedicated to tracing the history of a production company responsible for many of the greatest films to come out of Europe since the ‘70s. This programming gesture, which is hopefully met with an energetic public tonight, marks a shift in the cultural understanding of mid-century French cinema. Similar moves and rediscoveries should be expected to reimagine our current grasp on the history of world cinema.

Feedback Loop is a column by Nicolas Pedrero-Setzer reflecting on each month of repertory filmgoing in New York City.