Anthology Film Archives’ “Feedback, Part 2” series takes its title from Tony Conrad’s 1974 short—a Herculean effort to recreate the continuous loops of video feedback using celluloid: simultaneously shooting, processing, and projecting the same reel of 16mm film. In Saturday’s “Film Feedback” program, it is followed by Paul Sharits’s mind-bending Episodic Generation (1978). (His colorfully sabulous Axiomatic Granularity, 1973, plays the following day, in “Print Generation.”) In a 1978 issue of Film Culture, Sharits further defined the cinematic interests he originally outlined in his 1967 “Statement of Intention,” many of which concern the films in Anthology’s series: “celluloid, two-dimensional strips; individual rectangular frames; the nature of sprockets and emulsion; projector operations; the three-dimensional light beam; environmental illumination; the two-dimensional reflective screen surface; the retinal screen; optic nerve and individual psycho-physical subjectivities of consciousness.” Sharits was fixated not on the illusionistic capacities of cinema, but on the materiality of the film medium itself.

This sentiment couldn’t be truer for J.J. Murphy’s hypnotic Print Generation (1974), a structuralist film staple that begs the question of where, at which point, an image becomes a truly legible entity. For my money, Ernie Gehr’s unclassifiable History (1970), which plays right before, is the more interesting experience on a moment-by-moment basis, one that never provides viewers with anything immediately identifiable. It is perhaps the minimalist master’s most minimal film: Gehr removed the lens from his camera and exposed 16mm film through a piece of black cheesecloth. The result is frantic black-and-white granular patterns, constantly swirling as if the viewer has been stranded in space during a turbulent medoid shower. Gehr has described the film to me as one that doesn’t have a beginning or an end, that doesn’t even move forward or backward. The effect may be due in part to the fact that the film has changed length a few times over the years, its runtime continually reduced at the behest of its maker, who thinks even 22 minutes of these visuals is a bit much. (Gehr once mentioned offhandedly a two-hour version of History only eight people, one of them Annette Michelson, have ever seen; J. Hoberman wrote about viewing a 40-minute version of the film in 1982.)

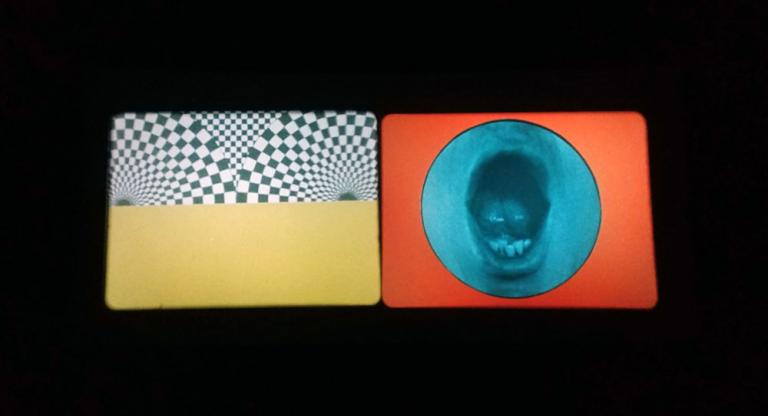

The substantial 16mm offerings are all certainly worthy of praise—I haven’t mentioned Takashi Ito’s dizzying Spacy (1981) or Scott Bartlett’s classic OffOn (1968). Three separate feedback-heavy intros of Doctor Who Anthology will play, two of which predate Bartlett and Tom Dewitt’s earliest experimentations. Many of the video-art pieces programmed later in the series, too, provide their own distinct pleasures. Stan VanDerBeek’s Strobe Ode (1977) finds varied, vivid pigment combinations across a series of circular strobe flashes, while Steina & Woody Vasulka’s Distant Activities (1972), much like Conrad’s Film Feedback, constructs a disorienting feedback loop in real-time. For those interested in additional context for the couple’s working methodology, the first episode of Vasulka Video (1978), an informatively informal six-part made-for-TV series, will also be shown.

The same type of whimsical adventurousness can be found in Skip Sweeney’s Illuminatin’ Sweeney (1975), a “greatest hits” of sorts for a wildly underappreciated San Francisco artist. It is playing on the same bill as Nam June Paik & John Godfrey’s still-revolutionary Global Grove (1973), which accurately predicted almost 50 years ago, with a level of ambition and confidence rarely matched in video art, that the “TV Guide will be as fat as the Manhattan telephone book.”

While those two works together might be capriciousness-overload for some viewers, it's a more forgiving option than VanDerBeek’s other film in the series, the oppressively dour Mirrored Reason (1980), in which the longtime Baltimore news anchor Denise Koch delivers a solemn monologue about a woman claiming she is being stalked by her “double.” A carefully placed mirror splits the newscaster’s face in half, effectively “doubling” her presence on the screen and connecting the piece’s image and text in a fairly obvious, self-serious way. The other videos in that program, titled “Mirroring,” pick up the pace a little bit, or at least employ the titular technique to more humorous ends. Joan Jonas’s Left Side Right Side and Duet (both 1972) serve as a much-needed reprieve, while Robert Morris’s Mirror (1971), accomplishes the same playful visual and theoretical feats as Gary Beydler’s better known Hand Held Day (1975), four years earlier. If Morris and Beydler go about capturing the natural world with minimal human involvement, Mike Stoltz’s With Pluses and Minuses (2013)—playing in the first “Aural Feedback” program—takes the opposite approach: by editing his 16mm film in camera, deliberately altering the volume of the audio and changing the focal length of each shot, Stoltz creates a version of the natural the world mediated through human agency alone.

The inclusion of a few performance pieces helped round out the largely materialist selections in the series. You get an entire program of Vito Acconci’s high-wire antics—including “Shadow-Play,” one of the three parts of Three Relationship Studies (1970), in which he appears to get into a scuffle with his own shadow—as well as one of Andy Warhol’s more accessible double-projection works, Outer and Inner Space (1966), in which Edie Sedgwick talks to herself, via video recording. The one that put the biggest smile on my face was Richard Serra’s Boomerang (1974), a typically simple yet comical study of human perception. Strapped with a pair of bulky, commercial-grade headphones, Nancy Holt proceeds to verbally explain the experience of hearing her own voice with a one-second delay. “The words are spilling out of my head and then returning into my ears,” she observes, stammering with difficulty. In a series dedicated to film and video’s innate material properties and their manipulation, it was a joy to watch this artist become as contorted and disoriented as the viewer of many of the surrounding works may well be.

“Feedback, Part 2” runs through August 2 at Anthology Film Archives.