The origins of found footage filmmaking are typically traced to the early years of Soviet cinema, when the filmmaker and editor Esfir Shub, and other talented editors, made agitprop films using material that had originally been shot for tsarist ends. The technique became widespread during the wars of the twentieth century, during which time the notion of “using the enemy’s weapons against them” was put into practice by both the Allies and the Axis. The idea was that in re-editing a newsreel, changing the order of shots, or adding a new soundtrack, the very opposite meaning could be created, if an audience was properly cued.

The digital descendants of this practice—remixes and mashups created from YouTube clips—reached ubiquity in the mid-2000s and then fell out of fashion as many filmmakers embraced the archival turn and focused on the materiality of celluloid instead of downloading whatever they could get their hands on. As online access to archival collections via platforms like the Internet Archive has expanded in recent years, with large amounts of material available for Creative Commons reuse, the practice of digital found footage filmmaking has merged these two strains, with filmmakers, media artists, film historians, and academics alike embracing the technique. There are a whole constellation of terms that are applied to these found-media works: compilation, collage, remix, mash-up, and détournement, to name just a few.

The Festival of (In)Appropriation, the “preeminent international showcase for experimental, found-media film and video,” has consistently cataloged this morphing field since 2009. The festival is directed by the film scholar Jaimie Baron, who programmed this thirteenth edition alongside Jennifer Proctor and Adam Sekuler. The festival’s name pushes for the term that Baron has suggested in her scholarship: the “appropriation film.” Baron favors this term because it underscores the notion of propriety and its converse, impropriety, that found-media experimentations toy with. Consisting of 16 films, this year’s program is a testament to the range of forms under the appropriation umbrella, and the ways that they question what is deemed proper in both filmmaking practice and historical discourse.

Many of the films in the program recall the analog origins of found footage because of their use of celluloid scans. One example is Timescraps: Film Threads and Sprocket Holes (2023), Krista Leigh Steinke’s “homage to the women who worked in the motion picture industry in the early part of the 20th century.” The film makes use of a range of digital techniques to emphasize the variegated beauty of film sprocket holes and edge marks, making us appreciate physical film objects and the (often female) labor that went into perfecting their color in the lab. Another is Luis Carlos Rodríguez’s Collage 42 (2022), an under-three-minute “divertimento audiovisual” using material from The Great St. Louis Bank Robbery (1959), which is now in the public domain. Rodríguez partitions the screen into 24 separate frames, separating the dramatic actions of the original film into a series of repeating vignettes that highlight the beauty of that film’s cinematography. The effect is reminiscent of an undulating storyboard and is very pleasing to the eye. The film also represents a successful use of digital techniques that simultaneously allows the original film object to remain legible.

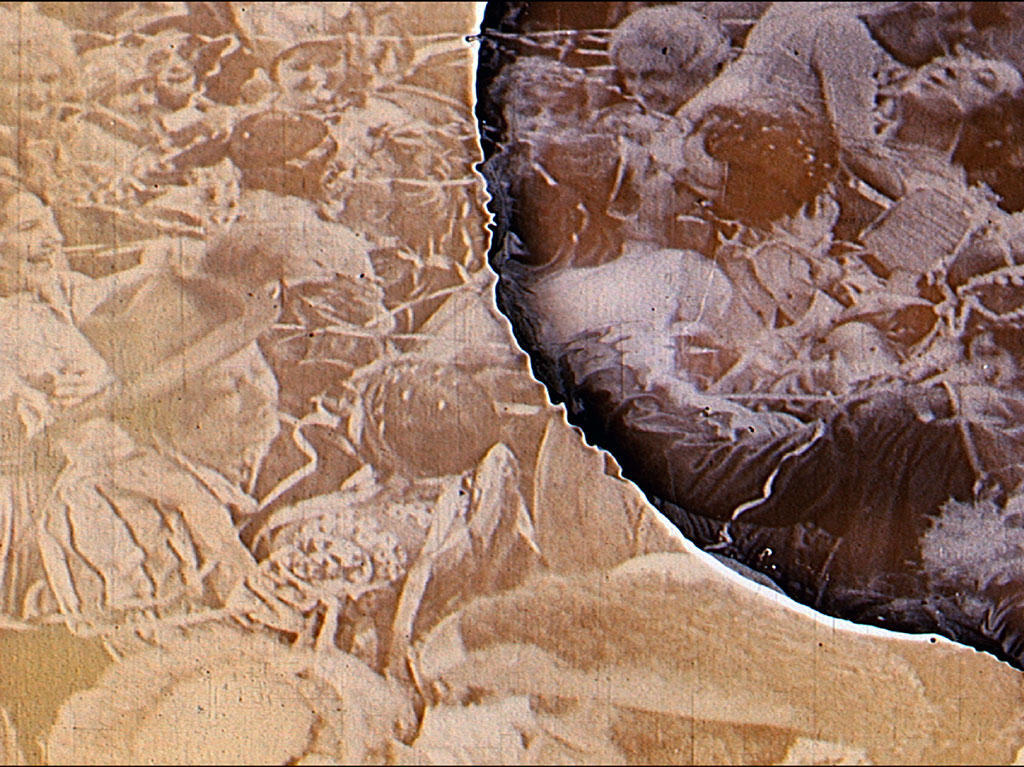

There is also a strong strain of musically-based offerings in this year’s festival. Tulipomania: You Had to Be There (2022) revealed itself to be a music video for the band Tulipomania’s new single. The program also includes a Bill Morrison offering, Her Violet Kiss (2021, pictured above), with music by Michael Montes. In this film, we are given information about the physical source of the material—a German film from 1928 whose nitrate print was located at the National Audio-Visual Conservation Center at the Library of Congress. The original film has aged beautifully, and the masked stranger who appears from behind the bubbling nitrate is truly haunting.

On the other hand, some of the films in the program are very much from the digital remix world. Cupid’s Fever (2021) by MilleFeuille feels like a classic example of the YouTube mashup. In this case, the content is vlogs showing couples in different stages of painful breakups or awkward conversations. Interspersed with these vlog images is another stream of images depicting children aiming bows and arrows (and sometimes guns) at live deer. The heavy-handed cupid metaphor set up by the film’s title becomes clear when the film ratchets up the cringe level to an absurd degree, along with increasingly gory hunting scenes. A YouTube appropriation of this sort feels surprising in 2024, as the format has somewhat receded in popularity. Cupid’s Fever is reminiscent of the infamous appropriation film Of the North (2015), which Jaimie Baron has described as a prime example of an unethical, inappropriate use of the original material from which it was created. In the case of Cupid’s Fever, the main lever of emotional weight comes from the feeling of violating others’ privacy or laughing at their misery.

Exemplifying the diversity in approaches to found-media is Dreams Under Confinement (2020), a masterclass from Christopher Harris that demonstrates the political potency of a simple détournement. In this two-and-a-half-minute film, a screen recording depicting various views of the Cook County Jail in Chicago via Google Earth is combined with audio from Chicago police scanners during the 2020 uprisings against police murder. The conceit appears self-evident now, but that is what makes it great, as Harris deftly matches the frenzied voices coming over the radio with an increasingly rapid pace of movement through the Google world. With its powerful critique, the film also expertly implicates its own source material into a regime of carceral visuality as it references Google’s well-documented role in collaborating with police forces via technological partnerships. The film enacts a form of counter-surveillance, but it also points to the limits of found-media practice in transcending the oppressive history of digital material when the latter is created and stored by massive corporations.

It is worth returning here to the point that in most historical accounts, found footage filmmaking is theorized as inherently political; however, this year’s program is muted in its critiques. There are references to current events: Eugenia Bakurin’s Long Time No Techno (2022) draws on “children’s films of the 70s and 80s” shot at the Odesa Film Studio, a site of many Soviet film productions that is now threatened by Russia’s invasion. Set to bouncing music by Momen Shaweesh, the film is a dynamic sizzle reel for the studio’s impressive archive of images, which includes the dancing workers of a piano factory and trampolining townspeople.

Each entry in the program pulls out another thread of the tapestry that is found footage/found-media/appropriation films. More than anything, the festival attests to the unsettled nature of this category and its nuances, which need more attention outside of the very small niche of appropriators and their fans. We have moved past the era of agitprop alone and into new territory in which filmmakers take up appropriation for various reasons: political, aesthetic, and ethical.The program’s grouping of short films in this way cuts across the confines of genre and audience in a way that is productive for thinking about how we use old footage today.

The Festival of (In)Appropriation #13 takes place tonight, June 29, at Anthology Film Archives.