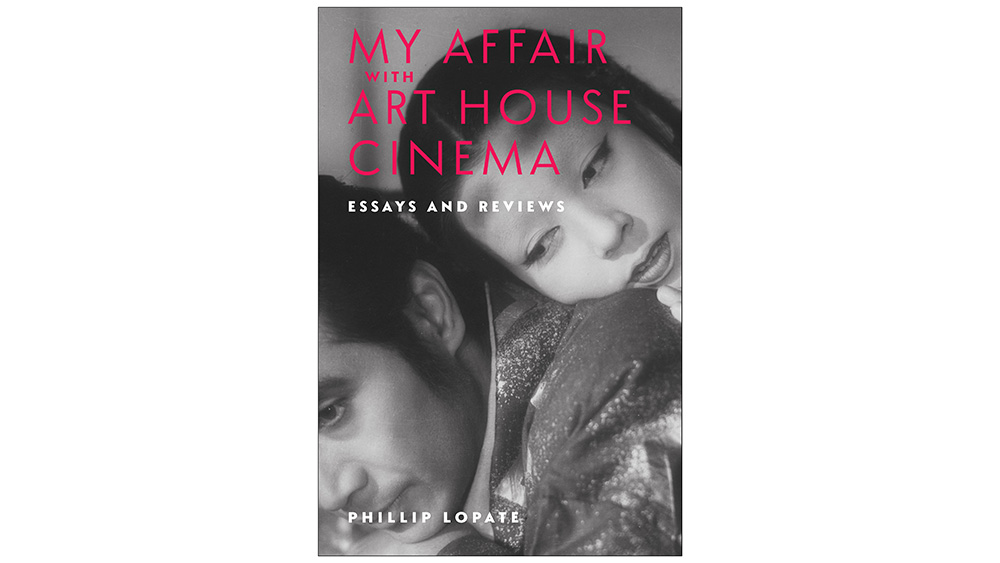

The cinephile, personal essayist, editor, and prolific author Phillip Lopate has long been one of our finest film critics. But his film writing has always been a side gig, albeit one pursued with ardent passion; hence, the hint of illicit romance in the titles of his two critical anthologies: Totally, Tenderly, Tragically: Essays and Criticism from a Lifelong Love Affair With Movies (1988), and his wonderful new collection My Affair with Art House Cinema (2024).

Lopate writes with tremendous authority, but brings an amateur’s joy to his writing. In one of his new book’s opening chapters, “How I Look at Movies,” Lopate, with deceptive ease and in just five pages, explains his aesthetic preferences. He writes that he is particularly drawn to directors like Michelangelo Antonioni and Jean Renoir, filmmakers who show people in groups and use space expressively.

“A big part of what still pleases me is the way a film stitches its characters to their environments—how it allows us to see a larger sociological and geographical perspective, how it carves up the space and keeps a flow going. The master of this fluidity was Jean Renoir,” he writes. But of course, this preference isn’t rigid. “Then again, I am happy with some directors, like Robert Bresson or Yasujiro Ozu, who resist fluidity and call our attention to the isolation of each composed shot.”

The book’s other curtain-raising chapter, before its 60-plus brief chapters on a wide range of movies and a section on individual film critics, is “On Changing One’s Mind About Movies.” It starts: “For those who have ever tried to palm themselves off as film critics or even to assert confident judgements about movies in social gatherings, the nagging awareness of just how unstable and fluid these judgments can be is a secret embarrassment, a threat, possibly a stimulus.” In this chapter, Lopate charts his evolving opinions on films, including Jacques Demy’s The Young Girls of Rochefort (1967) (upgrade), Ingmar Bergman’s Winter Light (1963) (upgrade), and Jean-luc Godard’s Two or Three Things… (1967) (downgrade). To see a film is to go on a journey and there are few writers who can share the steps of that journey with such lucidity and insight, as well as such a willingness to embrace and ponder contradictions.

At his Carroll Gardens brownstone, Lopate and I talked about his book and the upcoming screening of John Cassavetes’s The Killing of a Chinese Bookie (1976) that will take place this afternoon at the Museum of the Moving Image in honor of the publication. Concisely distilling the director’s project to haiku-length, Lopate writes, “Cassavetes clearly believed the self to be a constant bluff, a desperate improvisation launched in heavy fog.”

David Schwartz: How did this anthology come about? It’s been 25 years since your last collection of film writing.

Phillip Lopate: I've written a lot of film criticism and during Covid, I started looking over it and thinking that some of it was pretty well written, so wouldn't it be nice to collect it? The theme that emerged was that it was all art house cinema, because, frankly, most of it was commissioned by magazines, newspapers, the Criterion Collection, and so on. I was never asked to review a Marvel Comics movie. They somehow got it into their head that I was not the guy to do that, which pleased me because, in general, I wanted to review films that were challenging and that I like for the most part. There are not many pans in the book. It's mostly praise. Part of the book is a collection of reviews of feature fiction films; part is about documentaries and essay films, because that's a form that interests me a great deal; part was a series of essays about other film critics.

DS: It used to be pretty common to have published collections of reviews by specific critics, like Dwight MacDonald, Manny Farber, or Otis Ferguson. Today, many critics write for ten different outlets, so a collection like this is especially useful.

PL: It used to be understood that if you liked a writer, you wanted to read anything he or she said. But publishers have gotten a little more leery and they often try to impose some usually bogus theme on what is a random collection. I’ve done the same thing with my personal essays, so I've defended this form: random anthology.

DS: Randomness can be illuminating. I like how you organize the films alphabetically by the filmmakers’ last name, which gives the reader some surprising juxtapositions.

PL: Nobody has to read it from cover to cover, straight through. Poke around. Look at what I say about films that you want to learn more about, see if you agree or disagree. That's the way I did it.

DS: Let’s focus on the Cassavetes film, The Killing of a Chinese Bookie, that you’re showing at the Museum of the Moving Image.

PL: Cassavetes expanded the idea of what movies can be. He was an outsider and his films were often criticized when they first came out. At a certain point, filmmakers from around the world started cluing in on Cassavetes and realizing that he had developed a method that excited him—an epistemological method, a way of sinking into a scene and sinking into the image.

[Abbas] Kiarostami and Hou Hsiao-hsien were doing the same thing, creating an existential model of falling into the scene. In the case of Cassavetes, some of it had to do with what looked like an improvisational method. The irony is that he actually wrote this stuff out as screenplays, but it was acted as though it was improvisational. All the scenes evade the Hollywood idea that every scene should have one idea—the Syd Field screenplay thing. Some scenes go on and on, and they have more than one idea or more than one inflection point.

DS: In your piece about Chinese Bookie you also wrote that there are down moments where you’re just observing behavior.

PL: Exactly, the behavioral moment that is not necessarily about what's happening in the plot, but just observing individuals. And there are lots of minor characters. The central performance by Ben Gazzara is fascinating, because he's always torn between being authentic and inauthentic. It’s funny because Gazzara had a lot of trouble on the set—he didn't like the character he was playing. Well, guess what? The character, Cosmo, doesn't like himself either. He’s somebody who's trying to be suave; he’s the owner of the Crazy Horse nightclub; he keeps screwing up. He comes from a rough-hewn background and he's trying to put on his “Mr. Lucky” airs. And, he has all of these women that he takes around with him. He’s almost like a pimp. At every moment Cosmo seems to be pulled between what he's supposed to be doing and what he would rather be doing.

DS: It feels like it’s a self-portrait of Cassavetes.

PL: Yes, because Cassavetes himself said, people don't really know what they're doing. Only in movies do they know what they're doing, but actually, people don't know what they're doing. Cassavetes was always foregrounding this idea that Cosmo was confused and that he was trying to stumble toward something authentic, something that made sense to him; but, he knew he had to get through a lot of confusion. And that's certainly true with A Woman Under the Influence (1974), or Faces (1968), or Husbands (1970). The difference with Chinese Bookie is that it’s a sort of genre film, a crime story. And indeed, Cosmo takes a bullet. The genre provided an arc, a skeletal link, that he didn’t really have in his other films.

DL: It must have confused audiences. It was poorly received when it was first shown because it was a genre film, but it also wasn’t.

PL: Exactly. It’s funny to think of Jean-Pierre Melville at the same moment creating his stripped-bare genre films. And then there's Cassavetes mucking it up and creating a lot of confusion. But the two of them were experimenting in a way.

DS: I want to ask about your approach to writing. You’ve obviously studied criticism—you put together a film criticism anthology for the Library of America. And, I think your writing is distinctive in its mix of formal analysis, of understanding characters, of your craft in creating essays, and in your personal approach. How did this develop?

PL: When I first fell in love with movies, I was very much under the influence of André Bazin and Cahiers du Cinéma, a formalist approach. To some degree, Andrew Sarris was also doing that. So I would look at the frame, I would look at the composition. Did it make sense or not? I never lost that formalist perspective. However, at a certain point, I became much more interested in the psychology or the characters, so a movie that had a strong feeling for character began to matter as much, if not more, than a movie that knew where to put the camera. That layer came in and then I developed a whole career, essentially, as a personal essayist. I had this notion that criticism was also a form of doing a personal essay. Somehow your background, your perspective, your psychology was going to come through. I wasn't ashamed of using the letter I, of putting myself into it. I knew that I was concentrating on the way I saw the world, the way the world was coming at me.

DS: When you describe that, I think about so many lesser critics who write in a subjective way, as though the way they feel about a character is what's important, rather than making an argument. I feel like your writing gives us your perspective, but that you get very inside the film.

PL: Well, I am also interested in a kind of detachment, for want of a better word. For me, two films always came to mind when people asked what my favorite films were: Kenji Mizoguchi’s Ugetsu [1953] and Max Ophuls’s The Earrings of Madame de… [1953]. In both cases, you have a filmmaker who is observing behavior. Not exactly judging people, but doing it with a kind of sorrowful, “what fools these mortals be” aspect. So people fall in love, even though it's going to screw them up, or the potter [in Ugetsu] is going to leave his family and fail to take responsibility for them, until he comes back at the end and his wife is a ghost. I think that the formalism is connected to a sense of detachment. I think it was Douglas Sirk who said that lighting is the director’s thoughts and composition is the philosophy, or something like that. I really developed a love of film at a period when CinemaScope was coming in, you could suddenly deal with a larger frame.

DS: One of the effects of the way you write about film, and the way you see film, is that you are making an argument for seeing films in the theater. The sense of space is so important. This book is of course coming out at a time when a lot of people are viewing films at home, but the book makes a great case for seeing movies in theaters.

PL: Absolutely. In Chinese Bookie, Cassavetes uses a lot of gels. Toward the end, when Cosmo comes back to the club, he walks through these pools of light. It’s a way of distancing him, of adding a sense of myth to it. The use of space is very important to me, the use of space in order to convey psychology.

DS: One thing that came up during a recent discussion you did with Molly Haskell was the idea that what is known as the “golden age” of arthouse cinema—the 1950s and 1960s—was, in some ways, a smaller world than today’s film world. People were reading the same handful of critics and seeing the same relatively small number of films. That has changed a lot.

PL: Well, it felt like we were soldiers promoting film art. Don't forget that until the 1960s, there was still a suspicion that film wasn't actually an art. With the founding of the New York Film Festival, there was this assertion that, yes, we are an art. There was always this underground sense that, of course, it was an art. You always had people writing about it like that. But back then, you had a lot of people saying, “Come on, movies are just a way to pass time.”

One of the things that interested me was to define the artistry going back a long way. For instance, I have a piece in the book about Lubitsch, who I think was an incredible craftsman, an incredible filmmaker, and he was making movies for the masses, although they would often go over people's heads. People said, “Ernst, you're being a little European here.” In the late 1950s and early 1960s, you had people paying a lot of attention to Ingmar Bergman and Jean-Luc Godard, and the French New Wave and some of the Japanese filmmakers. I think that part of that sense that you're talking about, of a smaller world, was also a very competitive, sometimes mean-spirited scene, because critics were often attacking each other. You never see that anymore. The last person to do that was probably Jonathan Rosenbaum, to say, “Everybody is stupid except me.” [Laughs]

There was a feeling then that certain critics had exalted positions and that they had to be attacked. For instance, Bosley Crowther was a sitting duck. Everybody was going up against Crowther. When I was editing the anthology of American critics, I read a lot of Crowther and he was often right. He wasn’t a bad writer either, but there was a sense that he was fuddy-duddy or establishment, and that he wasn’t paying enough attention to young filmmakers, to experimental and independent film. He was only paying some attention to it. There was a sense that people were connected to each other, and sometimes they were on opposite sides. For instance, Pauline Kael disliked Andrew Sarris, but liked Manny Farber. I thought Manny Farber was great, a fascinating film critic. Molly Haskell had worked for the French Film Office and Sarris was doing an English translation of Cahiers du cinéma… You had these different groupings. Pauline attacked the auteurists, but she had her own auteurs.

DS: And John Simon was attacking everybody.

PL: Yeah, but that was his brand.

DS: I have to say, reading John Simon’s book about Ingmar Bergman is what got me interested in films.

PL: He was very intelligent and a darn good writer. I knew him a bit and he wasn’t nasty to me, just everybody else. But all of them, including Dwight Maconald, made up a bouquet. There was a sense that there were basically a dozen critics worth reading. I was very connected to the media, to the magazines they were writing for, the newspapers they were writing for. Well… They all went away, some of them still exist, like Esquire, which doesn’t have a regular film critic any more, and Vogue, which doesn’t either. With these magazines, there was this sense that you could actually make a living being a full-time film critic.

DS: Your book serves a very important function now. Since theaters reopened after Covid, I’ve been very actively going to repertory screenings. The repertory audience is definitely younger than it was before and I think that audience has heard about a lot of the films you write about, but haven’t seen them yet. A lot of the films you write about will be seen by repertory filmgoers now for the first time.

PL: I'm so happy that they're back. I went to introduce a screening of Melville’s Léon Morin, Priest [1961] at Film Forum and there were a lot of young people there. Thank god for repertory cinemas.

DS: Cassavetes seems to always do well.

PL: There’s such an energy to the films and there’s a side of Cassavetes—I know it sounds funny to say—that was permanently adolescent, a kind of searching quality not asserting adult wisdom. If the characters grope toward wisdom, it’s almost an accident if they get there.

The Killing of a Chinese Bookie screens this afternoon, September 1, at the Museum of the Moving Image as part of the series “Phillip Lopate Presents: Two Selections from My Affair With Art House Cinema.”