It’s been just over a year since India’s latest pogrom against Muslims savaged New Delhi, several months since the start of the country’s historic farmer uprising, a few weeks since the government arrested a teenage climate activist, and several days since China was revealed to have attacked Mumbai’s electrical grid as a warning against military escalation. Although his most recent work was released before any of these events took place, the documentaries of Anand Patwardhan — long unavailable for home viewing and mostly seen on the festival circuit, but now streaming on OVID — can help anyone understand why these events are unsurprising, and how tightly their causes are bound up with the common scourge of Hindu nationalism.

Patwardhan’s 17-film oeuvre begins in the 1970s with Waves of Revolution and Prisoners of Conscience, two sharp, short, and incriminating 16mm testimonies about state abuse under the dictatorial state of emergency (known simply as “the Emergency”) enacted by then-Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. Waves documents a student activist movement galvanized by Jayprakash Naryan, Marxist militant turned non-violent land reformist, and driven forward by songs, demonstrations, and millions of villagers beleaguered by famine, corruption, and poverty. The result is a mass movement energized by rebukes to state-sanctioned inequality. “That is why we call this a ‘Total Revolution,’” Narayan tells his followers, invoking the broad impetus for political, economic, religious, and cultural change. In Prisoners, the government’s response is unambiguous: detainment, torture, and defamation for dissenters of all stripes, many of whom remained imprisoned even after the Emergency ended.

It’s useful if not necessary to have some background on the Emergency before watching any of Patwardhan’s films, as is the case with a few other historical events that continue to define India’s contemporary dynamics — perhaps most significantly the long period of British rule and the bloody mass migration of Hindus and Muslims (known as “the partition”) precipitated by independence and the creation of Pakistan in 1947. It’s also helpful to have some familiarity with the caste system, a codified, colorist hierarchical feature of the Hindu religion that places a class of “Untouchables” (or Dalits, the term preferred by activists) at the bottom of society.

Besides Indira Gandhi, a few other figures loom large over the films and history: Bhimrao Ambedkar, who was born a Dalit, authored India’s constitution, and rejected Hinduism in favor of the teachings of the Buddha; Bhagat Singh, born into the Sikh religion under British rule and hanged as an avowed atheist by the colonial government at age 24; Mahatma Gandhi, whose saint-like symbolic status illustrates the hypocrisies of a majority bent on undoing his legacy of secularism and non-violence; and Nathuram Godse, Gandhi’s assassin and a hero to the Hindu nationalist movement.

Once fringe, the ascent of that movement hurtles with horrifying momentum through Patwardhan’s filmography, climaxing off-screen with the 2014 election of Prime Minister Narendra Modi in between Jai Bhim Comrade (2012) and Reason (2018). The former title refers to the slogan used by Ambedkar’s followers, while the latter evokes the religious assault on science and facts by cultish, militant Hindu nationalist groups peddling superstition for profit and political gain. Modi’s party, the Bharatiya Janata Party, has historically been, at best, an enabler of these groups, and, at worst, a front for them (the BJP grew out of the far more incendiary RSS, of which Godse, Gandhi’s killer, was a member).

Where the earlier films show how Modi — who stoked anti-Muslim riots in the 2002 as governor of Gujarat — and his ilk have incited regional mob violence, Reason demonstrates the extent to which India’s government has sanctioned fanaticism on a national level and thwarted investigations into the increasingly frequent murders of activists. Patwardhan is drawn to subjects who provoke the ire of extremist groups, and so has repeatedly had the misfortune of having to tack obituaries and epitaphs onto his interviews. High-profile politicians condemn the murders while sending conspiratory directives down the chain to the police officers who enable, ignore, and often commit them (these are ACAB movies to the core).

Patwardhan also understands how easily politicians are able to marry religious nationalism to neoliberal economic policies, the stratification of caste translating seamlessly to class. No surprise then that many of their staunchest opponents are Communist and Marxist revolutionaries. More than once Patwardhan praises the virtues of “the red flag,” waved proudly by the anti-nationalist Sikhs in In Memory of Friends and the Dalit activists in Jai Bhim. Even non-ideological activists are often accused of and jailed for being “Naxalites,” or Maoist insurgents.

Occupying an aesthetic nook between direct cinema, man-on-the-street, and essay filmmaking, Patwardhan’s style is refreshingly free of any pretenses of observational impartiality or rigid mechanical consistency, deploying voice-over and other basic techniques as needed, with polemical tact. His stamp as auteur comes more from his dialectical rigor, both in parsing his subjects’ assertions for strains of logic and in deriving structural momentum from the friction between ideologically opposed forces. Not Hinduism and Islam, which are only superficially (if undeniably) in conflict — as becomes clear during Patwardhan’s trip to Pakistan in his nuclear exposé War and Peace — but pacifism and militancy, secularism and religiosity, logic and superstition. Because these same dynamics are always at play, the films can be watched coherently in any order.

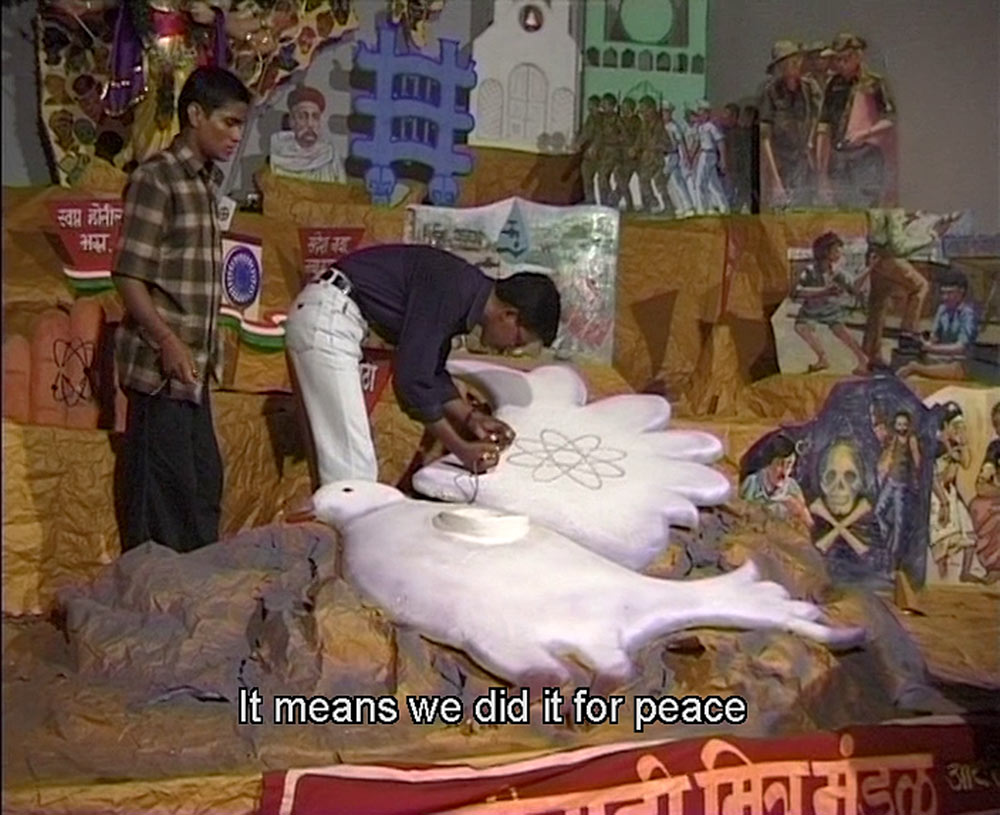

Many of Patwardhan’s most dubious subjects display a stunning mental alacrity of their own. Near the beginning of War and Peace, one man shows off a farcical animatronic display designed to celebrate India’s nuclear power, its centerpiece a giant mâché dove embedded with firecrackers. “The dove is the symbol of peace,” he explains, “and we set the blast inside it. That means we did it for peace.” There’s also the idiotic audacity of the code used to signal the success of the nuclear tests at Pokran: “The Buddha is smiling” (the test was also executed on the Buddha’s birthday).

Perhaps the most befuddling justification for atomic weaponry is as a salve for feelings of inferiority before Americans. Twice we see prominent politicians relaying an absurd and clearly fabricated story about a student abroad who feels shame in saying they’re from India, prior to Pokran. The easy metaphor of missile as phallus becomes central.

In the two-part The Father, The Son, and The Holy War, Patwardhan traces the religious link to virile posturing by exploring the ways notions of masculinity are used to advocate nuclear power and nationalism. A bizarre and unexpected cameo by “Macho Man” Randy Savage brings home the idea that all this hatred and aggression may really just be about dick-measuring with America. Alex Jones progenitors peddle oils that can make men “shoot like a bow from an arrow” and passersby tell Patwardhan, “If we saw a rape, we’d participate.” Lest we think there may be no hope for religious reconciliation, a sequence in Reason of counter-protests by both Hindus and Muslims against women demanding entrance to sacred spaces prompts the filmmaker to ask, “So Hindus and Muslims have united against women?” Without hesitation his interviewee responds, “Yes, yes.”

Of course, the most memorable of Patwardhan’s subjects over the years have been the righteous and the wronged, victims of atrocity and agitators of change. The marchers in Waves, the students in Prisoners of Conscience, Adivasi (indigenous) villagers in A Narmada Diary fighting a dam whose development has drowned their homes, the scientists debunking religious propaganda in Reason, and Patwardhan himself, who is threatened on camera and makes films under increasing threat of fatal reprisal — they’re all risking their lives and livelihoods over generations to fight for a humane, secular republic. Even the Canadian union organizers in A Time to Rise — Patwardhan’s only film made off the subcontinent — prove the revolutionary potential of the massive South Asian diaspora.

As the Indian state continues to flex its pious muscle through the occupation of Kashmir, the further marginalization of Muslims and other minorities, and the criminalization of dissent, Patwardhan’s films become more and more pivotal as playbooks for fighting back, as both histories and vehicles of resistance. They’re also monuments to the many who have died in the struggle. “We are ready for this sacrifice — not because we hate life but because we love it,” says an Adivasi activist preparing to drown themselves in protest. “We reject violence against others, so our own lives have become our best weapon.” Or as the poem that gives Patwardhan’s first film its title goes, “Sink or swim, I would plunge into the waves of revolution.”