In his 1990 essay “Towards a Minor Cinema,” Tom Gunning outlined what he deemed “a new influx of energy” that was starting to overtake avant-garde filmmaking practices at the time. The reign of structuralist cinema and its heady intellectualism had ended, and the idea of an experimental artist making major pronouncements about the possibilities of the film medium now appeared outmoded. Instead, emerging small-gauge filmmakers such as Peggy Ahwesh, Nina Fonoroff, Peter Herwitz, Lewis Klahr, Phil Solomon, and Mark LaPore made works that “assert[ed] no vision of conquest” and made “no claims to hegemony.” Their films were much smaller in scope—literally, as well as figuratively, since many of them utilized 8mm film as opposed to 16mm—and far more personal and intimate than the often imposing films of their mentors.

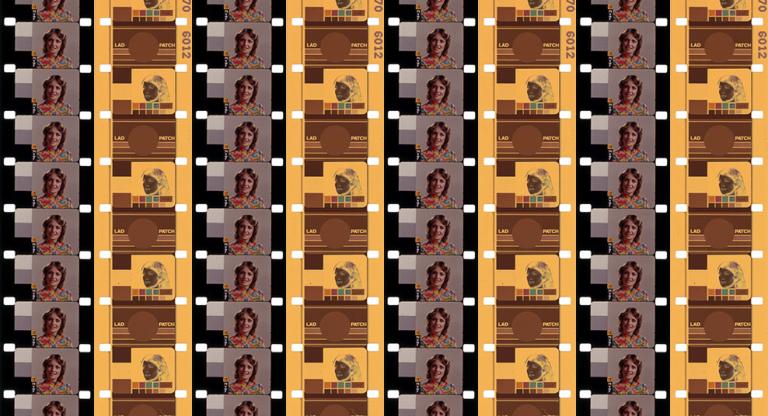

A student of both “major” (Paul Sharits and Tony Conrad) and “minor” (Ahwesh, Abigail Child, and Peter Hutton) filmmakers—as well as a close friend of Solomon—Eve Heller certainly belongs in the latter category, with an oeuvre comprising assemblages of seemingly insignificant images. Many of her films are constructed from a myriad of found sources, which are then run through an optical printer, magnifying their small imperfections (emulsion scratches, dirt particles, the occasional stray hair, etc.) until they become focal points in their own right. The original materials run the gamut, from informal Super 8 self-portraits of Heller herself—such as Self-Examination Remote Control (1981/2009), one of her earliest student films—to abandoned home movies like the weirdly hypnotic Last Lost (1996), a creepy artifact that finds a chimpanzee traversing a bustling 1930s Coney Island, its movements slowed-down and frequently reversed. Ruby Skin (2005) and Creme 21 (2013), two of her densest works, are compiled from educational films. The former reuses a short concerned with “Reaching Your Reader,” cutting up a crimson-soaked, faded 16mm print. The latter is a dizzying compilation of ’70s science-fiction flicks dealing in the two topics most prevalent to Heller’s cinema: duration and entropy.

These collections of discarded memories suspended in space and time are often fragmented to the point of unintelligibility, where they take on an almost ghostly quality, suggesting that much more may be lurking beneath their immediate surfaces. Her Glacial Speed (2001), for example, turns the everyday occurrence of spilled milk into a poetic configuration of abstract black-and-white forms. And in Singing in Oblivion (2021), Heller juxtaposes her own contemporary high-resolution footage of the Jewish Cemetery in Währing—highlighting its decaying foliage and unkept gravesites—with a series of antique glass negatives of unknown origin, initiating a dialogue between the present and the distant past. Personal effects, such as necklaces and pocket watches, have been optically printed to leave only an imprint of their general likeness, suggesting an insurmountable loss that never outright announces itself; the outlines of these cast-off knick-knacks, like the cemetery plots of Währin, serves as a stand-in for what was once there and which can never be restored. These three different types of imagery slowly begin to form a tapestry of generational trauma and dispossession, with the legacy of the Holocaust looming large over the ongoing proceedings. Like Heller’s other films, there’s an understanding here that, if these histories aren’t documented, even in some ostensibly “minor” way, these experiences, these remembrances, these neglected lifetime's worth of mementos, would simply vanish and be forgotten forever—much like the end credits of Last Lost, in which Heller’s own name, written in the sand, is washed away by the incoming tide.

A retrospective of Eve Heller’s work screens tonight and tomorrow, October 16 and 17, at Anthology Film Archives.