The neuroscientist David Eagleman writes that everyone dies three times: first when your life is over, then when your remains are interred, and finally “when your name is spoken for the last time.” We might consider adding a fourth death: when your hard drive crashes, or your smartphone gets wiped. We operate under the illusion that immortality is achievable through digital backups and cloud storage across a variety of devices and servers. But this strategy only creates a proliferation of vulnerable copies, not a flawless safeguard against loss or corruption; the technological march of progress requires existing media to either evolve or be outmoded, resurrected only by hardcore enthusiasts. The stewards of our digital archives and assets know that the prospect of upgrading digital storage systems can be a grim mortality check of the cost, time, and compatibility to migrate data to new software. In contrast, certain physical materials can endure centuries in both their original form and function.

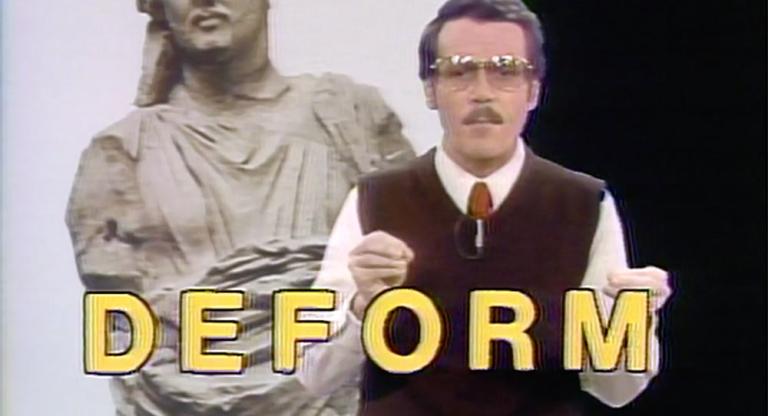

“A gravestone is actually about the briefest biography that you could write about somebody. It’s their name and their birth date and their death date. It’s the only thing many of us will ever leave,” says John “Fud” Benson, a second-generation calligrapher and stone carver at the John Stevens Shop in Newport, RI. Originally opened in 1705, the shop was purchased by the Bensons in the 1920s and is run today by Fud’s son Nicholas. In 1979, Fud gave voice to the meticulous craft of stone cutting and brush lettering in Final Marks: The Art of the Carved Letter. The 49-minute documentary by Frank Muhly Jr. and Peter O’Neill gives a glimpse into the small studio’s business of private and public commissions. Fud achieves the same high caliber of craft when carving a local tombstone request as when he rendered the letters for John F. Kennedy’s memorial at Arlington Cemetery, at just 25 years old.

Stone cutting is an ancient art form. Some examples from the first century A.D. can still be viewed and read on site today, providing us with a persistent glimpse into antiquity. Such engravings also facilitate printmaking, as when one creates a paper rubbing of a stone marker, a common memorial practice at both cemeteries and public monuments. In this way, Fud’s work allows for proliferating copies of the record of his hand by the record of someone else’s hand.

Typography and graphic design enthusiasts will appreciate how precisely Fud and his colleague, John Hegnauer, are able to letter by hand, with pencil, brush, and chisel; the making of typographic characters, painted line by line or carved by v-cutting a beveled channel, is astounding to watch manually evolve. Drafting designs, practicing alphabets, and maintaining the workspace at a job or in the shop appear as the remarkably meditative work routine of an analog design studio. Can we imagine the satisfaction and manageability of it today? Colored by Fud’s running commentary on the history and technique of his craft, it cannot go unnoticed how devoted he is to his material, his tools, and his appreciation for his work—just listen to him talk about stone, again. How many digital designers today might wax the same way about their daily fidelity to their design tasks?

Even in 1979, the John Stevens Shop faced competition from automation, as a competitor explains while a machine cuts rubber stencils, which will drastically reduce lettering time. A CNC machine could quickly execute these jobs today, no brushwork or lettering practice required, no eyeballing the curve of a v-cut made by hand. In his local cemetery, Fud points out the transformation of lettering and artistic design still visible on grave markers spanning hundreds of years, each scrawling closer toward his own modern, polished font, based on Hermann Zapf’s Optima typeface.

A grave marker is a material memory device, typically made of slate or granite, used to locate the deceased but sharing very little information about them. Historically hand carved, these markers are as much records of the human touch and personal aesthetic judgments that made them as they are records of what lies beneath. In our world, where everything is trending toward the computationally generated and automated, we might ask ourselves what it would mean to memorialize our dead without the input of a human trace. If, in the future, AI designs and carves our tombstones, then is humanity voluntarily letting itself be put to rest by the machine? A graveyard contains not only remains of the dead, but recorded evidence of the human hand—which, too, is dying out.

Final Marks screens through June 22 at Spectacle, accompanied by the short film “Conversations with Paul Rand” (Preston McClanahan, 1997), as part of the series “Counter Acts: Type & Lettering on Film & Video.”