The Fire Within (1963) is unique in Louis Malle’s wide-ranging oeuvre. A deeply personal, strikingly stylish work, the film is an expression both of the young writer-director’s obsessions and of a fleeting, in-between moment in place and time. It traces a day in the life of Alain Leroy, a writer whose riotous youth spent in alcoholic revelry has landed him in a clinic in Versailles. Despite his successful completion of the “cure” and four months of sobriety, Dorothy, his wife-cum-benefactor in New York City, has become increasingly unresponsive. Following a tryst with Dorothy’s best friend, Alain comes to a conclusion that once uttered propels the film to its thus-foretold, inevitable conclusion: “Tomorrow, I kill myself.” Alain spends his final day visiting old friends to proclaim his intentions, interrogate their willingness to go on living, and firm up his resolve.

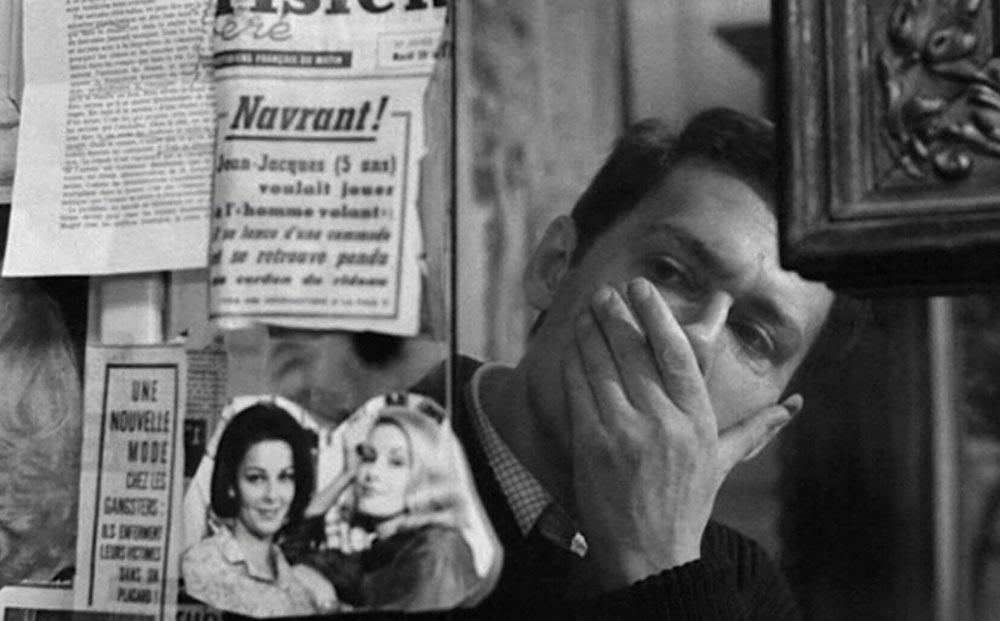

In the opening sequences, The Fire Within lingers patiently on partially obscured close-ups of Alain and his lover’s faces, the detritus of their wiled-away hours, the bare hotel furnishings; upon returning to his disheveled environs at the clinic, Alain gazes from the window at children playing ball, a woman hanging linens. Accompanying these beautiful if banal compositions are excerpts from Erik Satie’s Gymnopédies and Gnossiennes. Composed in the late 19th century, the succinct, deliberately paced piano pieces have been used in countless films to set a melancholy mood. An expressive shortcut like so many other minimal yet powerful compositions—Arvo Pärt’s Fratres, Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings—here the score serves as an auditory metaphor for the way in which Alain’s despondency delimits, empties, and ultimately severs him from his surroundings. His doctor suggests that “willpower” will see him into an alcohol-free future; what the film presents insists otherwise.

Though the music returns, often when Alain finds himself physically alone and confronted with his solitude, the majority of The Fire Within unfolds in mesmerizing, documentary-like conversations, with the soundtrack limited to diegesis. The shared sense of tragedy of the first half hour is displaced by something more alienating as Alain re-inhabits and begins to reckon with himself, descending into a dark night of the soul. As Alain declares again and again his own inability to remain a part of the world, he criticizes the way each of his friends submits to the compromises of aging. His harangues are rich with self-pity, jealousy, and humiliation, though they implicitly indict the audience for the same sins.

Malle based the script on Pierre Drieu La Rochelle’s 1931 novel Will O’ the Wisp, in turn inspired by the life of Jacques Rigaut, a Dadaist poet who, as promised in much of his writing, died by suicide at the age of 30. Drieu La Rochelle, an outspoken collaborationist and fascist, followed suit in 1944 upon the liberation of Paris. Malle spoke in a later interview of his own obsession with suicide at the time of production, as he faced the crisis of reaching his thirties; the film was, he claims, “cathartic,” “an act of rebellion by an overgrown teenager” driven by anxiety about his seemingly inevitable descent into establishment mediocrity. Something of this attitude infuses the Paris of the film: the Café de Flore, the bar of the Hôtel Voltaire, an apartment above Place des Vosges; each provides views of any number of women, inaccessible to our withering hero, and each introduces another dissolute youth in whose haggard face Alain sees himself vaguely, hopelessly reflected. The Algerian War was over and May of 1968 was yet to come—a wayward, unformed moment in the city’s youth is vividly captured, a time in which aging may have seemed the most dire threat to artists like Malle.

The Fire Within screens this evening, March 7, and on March 15, at Film Forum as part of the series “Jeanne Moreau, Actrice.”