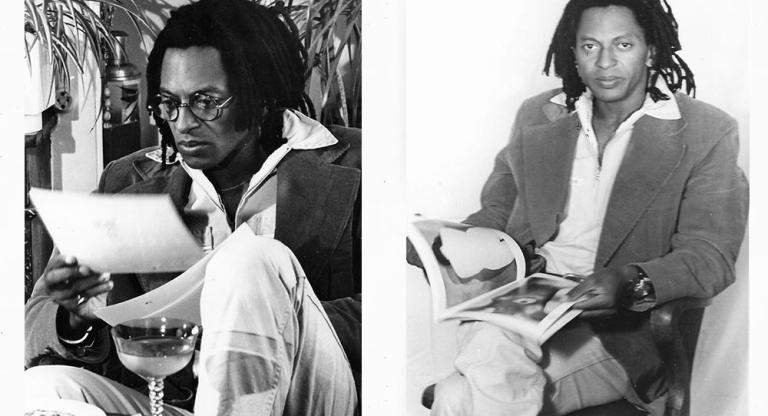

Just before Halloween, the filmmaker, novelist, and film historian S. Torriano Berry came to New York City from Iowa to attend the final screening of The Black Beyond Trilogy (1985–1992) at Spectacle Theater. Not only was the audience at the packed microcinema treated to a breathless Q&A with Berry afterwards, we were also graced with his acerbic commentary throughout the screening. The resourceful, shot-on-video, science-fiction/horror trilogy, a gonzo smorgasboard featuring an alien who transports to Earth through magnetic tape (Coming of the Saturnites), a deadly dollar bill (Money’ll Eat You Up), and a serial killer travailing the after-life (Deathly Realities), kept the crowd loud. One could only wonder why a filmmaker with such a hold over the audience has had any trouble getting his films in front of them.

Berry’s YouTube channel hosts a cofferful of re-edited versions of his past films, as well as excerpts from his popular Belizean TV series, Noh Matta Wat! (2005–2007). One of the gems on Berry’s YouTube channel is the thirty-minute version of his one-hour documentary, The Kusini Concept: The Pride and the Sabotage (2015). In the 1970s, Delta Sigma Theta, a Black sorority, raised nearly $2 million from their members to produce a film, Countdown at Kusini, planning to four-wall theaters—renting a space, selling tickets, and keeping all the proceeds, rather than splitting them with the theater owner and a distributor. All seemed destined for success until Columbia Pictures allegedly scuttled the roll-out. In our discussion, Berry, a natural raconteur, tells the rest of this story and many others.

Aaron E. Hunt: How did it feel to screen The Black Beyond Trilogy at Spectacle Theater the other night?

S. Torriano Berry: I hadn’t seen the films with an audience in over thirty years, so it was definitely an experience. The fact that people were still engaged, laughing when they were supposed to laugh and jumping when they were supposed to jump... Of course they missed a couple of the cues I was looking for, but overall it was good... I will admit that I got pretty excited for the screening a couple weeks ago, going to New York for it and everything...

I believe work does no one any good sitting on a shelf collecting dust. Even though YouTube is really good for at least having it out there, I have yet to monetize my YouTube channel in any way. Looking at the views, I don’t think I’d be making any money anyways. [laughs]

AH: You’re constantly re-editing and restructuring your films.

SB: I see them as rebirths.... A project is never finished, eventually you just quit. [laughs]

But after a while, you’re able to see your mistakes or see what you should’ve done, and if you’re able to go back and fix it, you go back and fix it....It continually grows, it continually changes. It’s a constant unfolding of the story that began a long time ago.

AH: You said you made Money’ll Eat You Up while teaching at Howard University. What about the other films you showed?

SB: I produced [The Coming of the Saturnites] when I was an access coordinator at Group W Cable in Gardena, California. I [had] produced The Connection (1985), the one with the guy with eyes on the back of his head, in Iowa, [where] I was working at MCTV, Multicultural Television, which was a small cable-programming company….After about a year and a half, I realized I wasn’t doing the kind of work I wanted to do or making the kind of money I needed to make.... I called ... my [former] manager at Group W Cable and I told him I was thinking about moving back. He happened to be looking to fill a position. So I was like, “Cool, that’s fate!”

I lived my life for many years with this fatalistic approach: If it’s meant to happen, it will happen. If it isn’t, it won’t. That didn’t work out, because I’m not where I thought I would be. I should have fought a lot harder for some of the things that I wanted to happen. And sometimes, when Fate would drop something in my lap, I’d accept it when it might not have been the best route for me to go. There was a long time where I felt I was put on this planet to make movies.... I knew my path was set as long as I put one foot in front of the other. When the time came, the contact, the connection, things would happen. Things would work. I’d make it.

Wronnnggg! [laughs] I was so wrong! But life was simpler back then.

AH: I think your films will stand the test of time.

SB: I hope so.... One thing I’ve been pretty proud of myself for is that I generally put myself in a position where I had access to equipment and facilities and could continue to do work.... The thing is, the more you can do yourself, the less you have to pay somebody. I’m a one man band: give me a camera, a mic, and some lights, and I’ll make it happen. I don’t need anyone to light it, edit it, or shoot it. As long as it’s in my power, it’s done. My problem has always been the things I didn’t have control over, like distribution.

AH: You’ve been heavily involved in the preservation and reconstruction of James and Eloyce Gist films. Their Hellbound Train (1930), Verdict Not Guilty (1932), and Heaven-Bound Travelers (1935) originally played for Black church audiences.

SB: For years I didn’t know about Heaven-Bound Travelers, even though I was heavily involved with Hellbound Train, which supposedly James Gist had already shot, edited, and screened before he met Eloyce. She was instrumental in replacing the title cards and possibly adding a scene or two, from what my research revealed. That makes sense because in the footage, [which] was rediscovered in a vault in the Library of Congress, there were just a bunch of pieces and fragments of film that they had put back together, because evidently the film had gotten old and brittle and broken apart.

There was really no way for me to have any idea how the film was structured, except for the title cards. I’m pretty sure he did a lot of in-camera editing. In fact, there were a lot of double frames and jump cuts, as if he [had] started and stopped the camera. The actors would look at the camera like he was telling them to do something. I cut those and the jump cuts out. There were also a lot of these long running train shots that would go on for like a minute or two. There was no way in hell I could figure out how the film was originally edited and constructed. I spent a lot of time trying to figure it out, but there was no way I would ever know. I felt I should cut it with today’s audience in mind. Today, people don’t want to sit through a two-minute shot of a train coming down the track. So I would cut between the train and the action shots.

AH: There’s always backlash to things like that.

SB: …I think I was in film school when they started colorizing black and white films. People were going, “Oh! How are you gonna do it like that? That’s not how that film was!” I guarantee that if a lot of those directors could have shot in color, they would have. Maybe they would have liked to do something different but didn’t have the resources, the time, or maybe even the talent. Maybe their editor wasn’t the best editor in the world. Maybe it could have been a better film if it had been edited differently.

AE: What about your cut of Countdown at Kusini?

SB: The first time I had heard about Countdown at Kusini was probably my first week of film school at UCLA. I was talking to someone who has become a really good friend of mine, Robert Wheaton.... He asked me, “Have you heard of the film the Deltas made?” … Well, the thinking was, if they have 800,000 members, and all 800,000 could be counted on to support the film, let’s say with $5, then $5 x 800,000 gets you a lot of money. If you can make the film for that amount or less and those same members then go see the film, it breaks even automatically. Add in their partners, family, and neighbors, and all of that is profit.

I said, “That’s brilliant!” Then he said, “But they lost their money.” I asked how, and he shrugged his shoulders. That concept stayed on my mind all those years. It was a fool-proof concept; how did they lose their money? Flash forward twenty years to writing The 50 Most Influential Black Films with my sister Venise T. Berry.... I specifically wanted to put Countdown at Kusini on the list because it was important and could have changed the way Hollywood did business.… Ossie Davis and Dr. Jeanne L. Noble, the head of Delta Sigma Theta’s Arts & Letters Organization, which oversaw the project, basically said the distributor did not coordinate the release of the film with the Delta chapters. They made their own release schedule without telling the Deltas where they were sending the film, or opening the film. So the Deltas never even got the chance to go out and sell tickets and beef it up when the film opened.

In fact, Dr. Jeanne Noble told me they had a premiere…. It was packed, standing room only. The mayor was there, the governor was there, they had lights out in front sending light beams through the sky. It was a big deal. Then the print of the film never showed up. They never had the screening, and they found out the next day that Columbia had opened the film in Omaha and didn’t tell anybody. In my view, that’s sabotage. But the Deltas took it on themselves as if they failed and hadn’t done what they needed to do....

I remember when I finally saw it, because there was a print at the UCLA Film & Television Archives.... I was very disappointed with what I saw.... So I decided to make a cut of the film I call the Clayton cut. I restructured and recut the film…. The result was a faster and better film, in my opinion.

There are people who will say, what gave you that right? [laughs] Huh! Me? I had access to the film and the ability to, in my opinion, make it a better film.... When the film came out, it was panned a lot. “The Countdown to Mediocrity” was one of the newspaper headlines. Forty years ago you put a film out there that got panned, why bring it out with the same problems it had forty years ago? If you gave a speech with your fly undone, toilet paper on the bottom of your shoe, are you going to unzip your pants and tape some toilet paper to your shoe to do the same speech forty years later just because it’s how it happened the first time?

AH: I was very impressed by your running and stunt work in Rich (1983), your UCLA film about a kid in the inner city who wants to get into college.

SB: [laughs] Don’t ask me to do it today.... I had cast all of the roles except for the main character, Rich, and it was two days before production. I don’t know where this came from, because I never imagined doing any acting, but for some reason God or somebody put it in my head and my heart. I was 24 at the time, and Rich was supposed to be 18, graduating from high school. I pulled out my razor and shaved off my mustache, looked at myself in the mirror, and thought I might be able to pull it off.

I wrote it, produced it, directed it, I did all the original music, I thought for sure Hollywood would say, “Woo! We can save a lot of money with him!” [laughs] But that didn’t happen.... After [Spike Lee] saw the film, he asked me what it was like acting in my own movie, so I thought maybe I inspired something. But years later he said he didn’t remember the discussion....

When he came out with She’s Gotta Have It in 1986, I knew that train was coming. I had done some research, and when I did The 50 Most Influential Black Films book, I refer to this fifteen-year feast and famine cycle that the industry seems to have with Black films. Starting back with Oscar Micheaux, the Lincoln Motion Picture Company, those early companies that came out to answer Birth of A Nation around 1915, 1920s. That was the first feast, and it lasted about five years. Some Black films were made and then they trickled off for a ten-year famine, where [the] only films [that] were made address a specific issue in the Black community or have a single Black star. Of course, that period was so palpably embodied by Paul Robeson. And then came The Cabin In The Sky and Stormy Weather [both 1943], the Black musicals. They lasted for a few years, and then ebbed off and disappeared.. Then came the problem pictures, Pinky, Intruder in the Dust [both 1949], Sidney Poitier films…. Then, once again, they died out for another ten years or so. In ‘71 the Blaxploitation films came, and once again, after five years, they trickled out.

So, if the Blaxploitation films trickled off in ’76, what’s supposed to start in ’86, ten years later? A new feast. I knew it was coming. I saw it coming, and I was trying to be right at the station, ticket in hand, to get on the bus and ride. But somehow, somebody must have called my name, I looked, and when I turned back around the bus was gone, and Spike was on it, the Hudlins were on it, and the other brother, what’s his name—John Singleton. [laughs] Somehow I got left at the platform. I still don’t know how that happened.