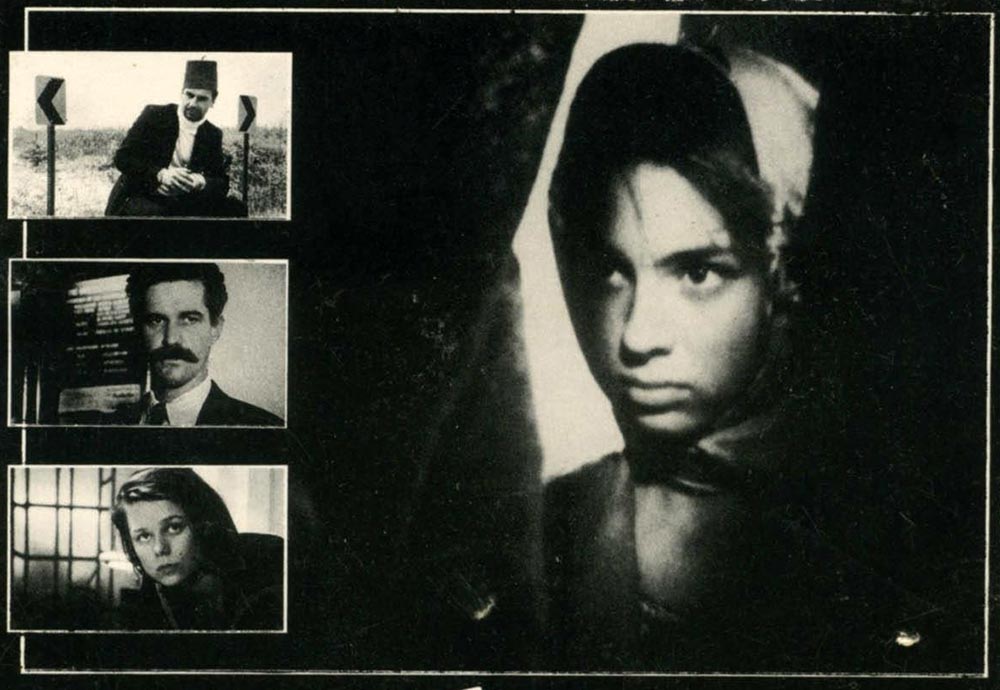

Nearly every actor in Liza Béar’s wry, shoestring-budget political drama Force of Circumstance (1990) was plucked from the then-bustling downtown Manhattan arts orbit. Boris Major—a childhood member of Squat Theatre, the bohemian theater company that staged experimental dramas from its 23rd Street storefront—plays a young Moroccan who travels to Washington, D.C., to deliver a cache of documents to a journalist on the eve of her country’s 1984 Bread Uprising. Meanwhile, preeminent Super-16 filmmaker Eric Mitchell, sporting a bright red fez, is an envoy of King Hassan, sent to the States to scope out a new residence for the monarch, who plans to abscond should the crown fall. Their parallel stories criss-cross with a parade of droll supporting characters: spot Lounge Lizard Evan Lurie as a Dooley Wilson-ian hotel ivory-tinkler, Steve Buscemi as a scene-stealing pig farmer, and a transatlantic coterie of Washington wheelers-and-dealers that count among their number Rockets Redglare, TV Party’s Glenn O’Brien, and James Chance.

The film is roughly about the flow of information and networks, and the hidden contingencies that structure them—topics Béar would know a thing or two about. In the ’60s, she had worked in trade press on London’s Fleet Street before heeding the siren call of the nascent underground, eventually landing an editorial gig at Manhattan’s Evergreen Review. She co-founded with Willoughby Sharp Avalanche (1970–1976), the storied art rag that covered the ground floor of East Coast conceptualism by running long-form interviews with figures such as Vito Acconci, Terry Fox, and Lawrence Weiner, and by commissioning artists to create pieces specifically for the the magazine pages. The varied contents of the periodical—which ranged from a ten-page text by Hanne Darboven composed entirely of numerals to short-form, proto-social-media dispatches called “Rumblings”—rarely included conventional essays or criticism, and often toyed with publishing conventions and the nature of communication itself. (This was a sensibility carried through the magazine’s thirteenth and final issue, the cover of which proudly displayed the operation’s modest financial ledger.)

It couldn’t have been too far a leap for Béar, then, to participate in the generation of late-’70s artists involving themselves with telecommunications technology, when developments such as public cablecast and satellite transmission facilitated both newfound local access and global connectivity. Béar dabbled in both. With sculptor Keith Sonnier, she developed Send/Receive Satellite Network (1977), a three-day experiment enlisting a group of bicoastal artists to communicate over a NASA satellite feed. Later, she initiated Communications Update (1979–1991), a weekly public-access show that covered both public policy around telecommunications and aired artists’ contributions, which ran the gamut of performance art, sketch comedy, and video vérité. In the case of both projects, the goal was political, aiming to wrest the means of communication from unilateral control and in many cases to reveal how corporate, governmental, and militaristic interests influence who is able to transit what.

It was under the auspices of Communications Update that Béar traveled to Morocco to produce Polisario: Liberation of the Western Sahara (1981), an interview with a United Nations representative for the Sahrawi rebel group known as the Polisario Front discussing their conflict with the US-backed ’Alawi dynasty. Béar’s experience of being in the north African country at the onset of the 1981 Casablanca bread riots was channeled into a subsequent video titled Oued Nefifik: A Foreign Movie (1982), a travelog-cum-comedy-of-manners following a Tati-esque tourist named Monsieur Hue Low as he navigates the realities of Morocco.

Force of Circumstance was an expanded, more formally ambitious examination of the Sahrawi resistance to the Moroccan monarchy, the American empire’s influence on global affairs, and the travails of pre-digital information circulation. However, as the director puts it, this is by no means a “one-issue film.” The pace ambles with a levity typically reserved for a slice-of-life picture, taking in bedside conversations, high-society functions, and backroom deals with an eye to the emotional lives of the characters, a reflection of the banal and vapid folly that charges international relations.

Force of Circumstance screens this afternoon, January 29, at the Museum of Modern Art as part of “To Save and Project: The 18th MoMA International Festival of Film Preservation.”